Reel to Real: New Books and Films on Bob Mackie, James Bond and Gucci Emphasize How Celebrity and Popular Style Remain Intertwined

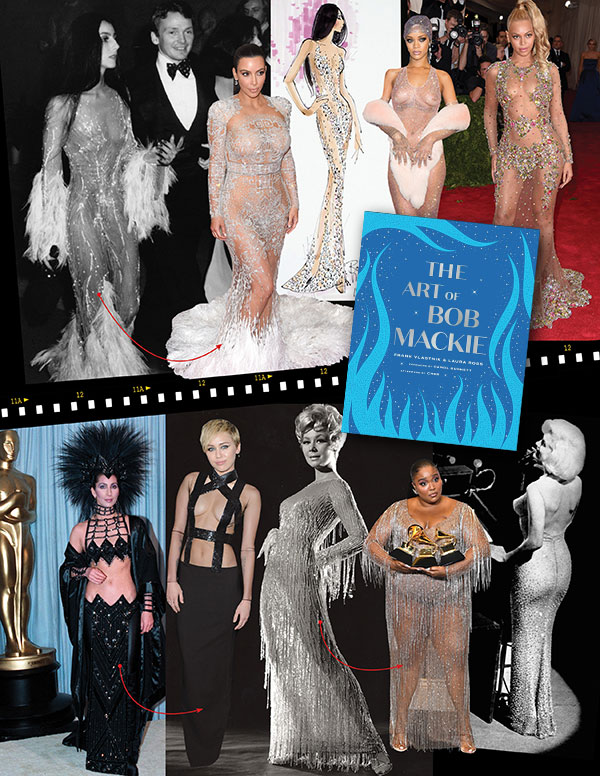

Singer Cher and fashion designer Bob Mackie attend The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Insitute Gala Exhibition "Romantic and Glamorous Hollywood Design" on Nov. 20, 1974 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Photo: Ron Galella / Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

“What Hollywood designs today, you will be wearing tomorrow,” couturière Elsa Schiaparelli once said, explaining the complex cross-pollination of film and fashion that has existed since the birth of the movies. The recent Netflix series Halston — which stars Ewan McGregor as America’s first celebrity fashion designer — was a timely reminder of how Hollywood glamour, modern celebrity and popular style are still intertwined. In anticipation of the season’s fashion highlights, we look at three enduring trendsetters who made their mark on the screen and whose sway over fashion made a lasting impression.

Bob Mackie: The Sultan of Sequins

Provocative, nearly naked gowns worn by celebrities like Rihanna, Beyoncé and Kim Kardashian have become routine on the red carpet. The boundary-pushing style is also an on-stage staple for entertainers from Jennifer Lopez to Demi Lovato. For every towering headdress and barely there frock, you can thank Bob Mackie.

Mackie famously designed the sublimely over-the-top, sheer, beaded and feathered outfit Cher wore to the 1974 Met Gala (and on the 1975 cover of Time), as well as her outré 1986 and 1988 Academy Award outfits. These style moments are an indelible part of her legacy, but they were hardly the first of such ensembles, as we learn in Laura Ross and Frank Vlastnik’s The Art of Bob Mackie (which came out Nov. 9). The coffee table tome is the first-ever comprehensive and authorized showcase of Mackie’s life and work, which was beamed into millions of living rooms on the small screen and helped shape (and sometimes shock) contemporary taste and elevate the definition of glamour.

The Art of Bob Mackie lavishly chronicles creative partnerships with luminaries like Diana Ross and Mitzi Gaynor, two decades of Emmy-winning variety specials, and Oscar nominations for Pennies from Heaven, Funny Lady and Lady Sings the Blues. Not only are there never-before-seen sketches and personal photographs (including his first showgirl costume, made at college), but it’s bookended with appreciations from two of his most famous long-time collaborators: Carol Burnett and Cher.

Mackie, 82, began his career as a sketch artist for film, drawing for legendary costume designers Edith Head and Jean Louis; for the latter, he sketched the rendering of the notorious rhinestone-covered “naked” dress Marilyn Monroe wore in 1962 to serenade President Kennedy on his birthday. It would prove prescient: Mackie debuted his own version in 1969. In the opening number of her second network special, curvaceous South Pacific star Mitzi Gaynor wears the clinging, nude illusion gown (made from a flesh-toned, knit fabric called soufflé) that launched thousands of imitations.

Bored with the slow pace of movie production, Mackie had switched to television a few years earlier when fashion and costume designer Ray Aghayan hired him as an assistant on The Judy Garland Show. Together, in 1967, they won the first Emmy ever awarded for costume design, for the television musical Alice Through the Looking Glass; their professional and long-time life partnership would last nearly 50 years until Aghayan’s death in 2011.

In her 2010 memoir This Time Together, Burnett devotes an entire chapter to Mackie, who designed as many as 50 costumes a week for her eponymous variety show from 1967 to 1978 (at one point, he did the same for Sonny and Cher across the hall). In the foreword to this new book, the comedian reiterates that hiring Mackie was “one of the smartest things I ever did.” His brilliant work for Gaynor is what first caught her eye. “I marvelled at the costumes,” she writes. “Not only were they beautiful, but when it was required, they were funny!” Burnett also credits his witty costumes for influencing how she’d play characters in some sketches.

With apologies to the old adage, “sequins are easy; comedy is hard,” Mackie was able to shift seamlessly between the two. His range includes knockout original high fashion, like the glimmering, salmon-pink halter gowns The Supremes wore in their 1969 GIT: On Broadway special (the ones that erupt in a surprise of feathers at the hem), as well as outlandish but cleverly conceptual get-ups for comedy sketches.

Use the words “Bob Mackie” and “That Dress” in a sentence and they might just as easily refer to his razzle-dazzle for Cher as to the sketch widely acknowledged as one of the funniest moments in the history of television: Burnett’s Starlet O’Hara dress in the 1976 send-up “Went with the Wind.” Mackie fashioned the antebellum parody gown – now in the Smithsonian – from green velvet draperies, leaving the tassel sashes and curtain rod hilariously intact. The appreciation of his genius transcends generations: An upcoming Mackie documentary, for example, features 90-year-old Gaynor alongside super stylist Law Roach of Céline Dion fame, who once dressed Tiffany Haddish for the MTV Awards in a tribute to Mackie’s Gone with the Wind spoof.

Mackie was raised in suburban Los Angeles by his grandparents. “Radio was my biggest influence,” he recalls in the book. “I could visualize the mysteries I listened to, but I also loved movies, especially musicals and adventures. Showgirls, pirates … I wanted so badly to live in a Technicolor world.” And he has. His glitz has graced Broadway, Las Vegas and opera stages, and the wardrobes of stars like Diahann Carroll, Whitney Houston, Bernadette Peters, Juliet Prowse, Carol Channing, Lucille Ball — and even Elton John, whose “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” stage outfit was recreated for the Rocketman biopic. As U.S. actor and Drag Race impresario RuPaul once said: “Anyone who has ever done glamour has had to pay homage to Bob Mackie.”

James Bond: Nobody Does It Better

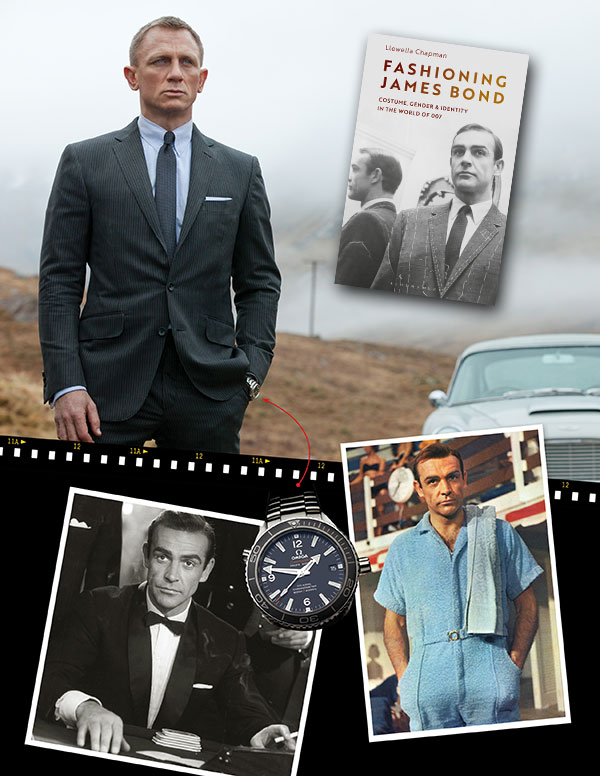

When we first meet James Bond, he’s at the baccarat table. The camera pulls back from the dealer and glides over Sean Connery’s shoulder, which is clad in an immaculately cut, midnight blue tuxedo. It then swivels to take in the fine silk lapels of his dinner jacket and lingers on the cocktail cuffs of his shirt as his manicured hands turn over the cards. All this before his face is revealed, let alone the delivery of his signature “Bond – James Bond” introduction.

This explicit appreciation of clothing in Dr. No, the first film adaptation of the globetrotting British secret agent novels created by Ian Fleming, speaks volumes about the MI6 agent codenamed 007. It signals that what he’s wearing matters and sets the tone for what, since 1962, has become the ne plus ultra of menswear icons on the screen. The global appeal of the mainstream’s most enduring swashbuckling hero — the Errol Flynn of espionage, if you will — wields influence.

“You see the finest cars, the most beautiful suits, really interesting actors portraying the characters that have evolved over time — and incredible design,” says Canadian-born, New York-based fashion expert Bronwyn Cosgrave, curator of the blockbuster touring exhibition “Designing 007: Fifty Years of Bond Style” that broke attendance records around the world.

No Time to Die continues the tradition. The 25th Bond installment features Daniel Craig in his fifth, and final, outing in the role and his fourth dressed by Tom Ford. The association with Craig’s cerebral, edgy Bond and his distinct sartorial legacy has brought unprecedented profile to what was then a fledgling luxury brand. Think of the memorable moment on the boat in Quantum of Solace when Craig’s Bond sports a shawl-collar Ford cardigan, “styled to look like Steve McQueen — that was massive,” says Cosgrave, a fashion journalist and bestselling author, documentary producer and host of the podcast A Different Tweed.

Most importantly, as she declares: “What the Chanel jacket is to women all over the world, Bond’s suit is to men.”

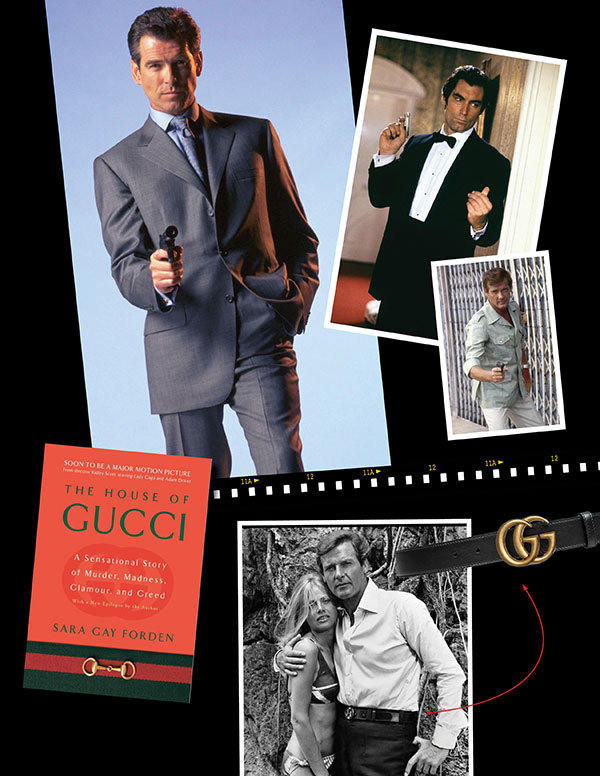

That holds true regardless of who tailors the suits or who embodies the character. Connery’s early look was designed by Anthony Sinclair, whose slim but not overly contoured, hourglass silhouette is often referred to as a “Conduit cut,” Cosgrave explains. It remains the Bond blueprint, whether it’s Stefano Ricci’s flannel suiting for a brooding Timothy Dalton or Pierce Brosnan in Brioni’s relaxed tailoring. “All of them were made with that suit in mind,” she says, “but in accordance with the style of the actor — their shape, their physique and their character – what they brought on screen. With [tailor] Douglas Hayward and Roger Moore, Roger was this witty guy and his jacket lapels are a bit wider, the trousers have a bit of a bell-bottom. It was actually conservative as opposed to what was going on at the time.” Cosgrave points out how Bond’s fashion sense has to be reflective of the time while also being timeless, as well as always “thinking forward — with the gadgets, with the interior décor — it was also always a few steps ahead of the contemporary.”

Over the movie franchise’s nearly 60-year history, as generations have immersed themselves in the spy’s elaborately designed world and emulated his suave sartorial trappings, Bond’s élan has also given men licence to care about fashion. Between the blogs and podcasts meticulously devoted to 007, whether it’s the collar spread of his Turnbull & Asser shirts or the particular Omega watch style he’s worn for 25 years since GoldenEye, we’re never more than a few keystrokes away from bottomless Bond coverage. In her new book, Fashioning James Bond, film historian Llewella Chapman likewise considers the history and meaning of the on-screen style choices since Dr. No, including all the supporting characters. One of the most engaging aspects of Chapman’s in-depth analysis is the way small fashion details (like an unexpectedly rugged Barbour coat), from Connery to Craig, have expressed subtle shifts in the secret agent’s personality.

Not that all Bond devotees have Aston Martin fantasies and bespoke suit dreams. The franchise has generated its share of coveted kitsch, like Roger Moore’s safari suits. In menswear label Orlebar Brown’s official 007 collaboration, for example, the heritage-inspired collection takes its cues, variously, from Thunderball (short retro swim trunks), Dr. No (a polo made of towelling) and Octopussy (the Harrington jacket). The pièce de résistance is a replica of the light-blue, terrycloth romper that Connery sports in Goldfinger. It is decidedly not for the timid double-O enthusiast.

Arguably every aspect of the juggernaut franchise is now considered iconic, from composer Monty Norman’s jaunty theme tune and the elaborate villain lairs to the rotating cast of Bond girls, as well as memorable title songs performed by greats like Dame Shirley Bassey and Tina Turner. (The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra’s upcoming Bond 25 album, out Oct. 1, includes new arrangements). The next Bond, whoever he (or she) may be, has quite a suit to fill.

Gucci: Dressed to Kill

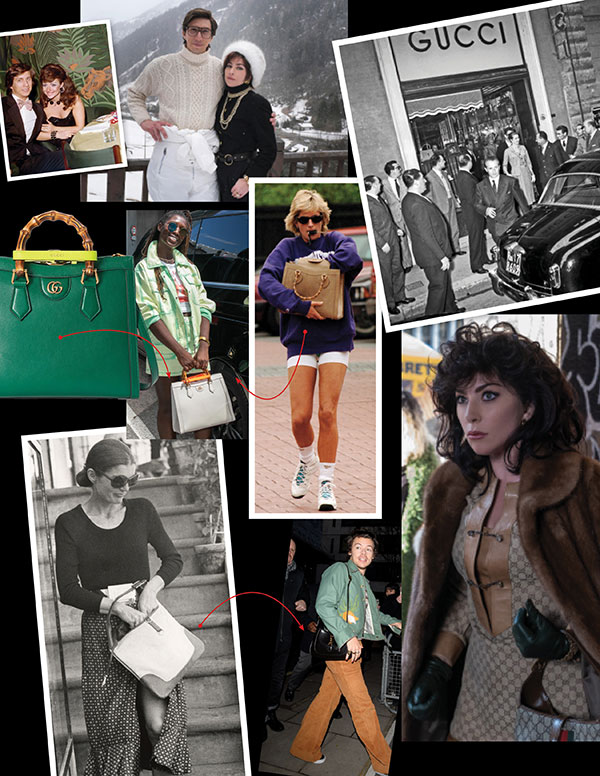

As it happens, Roger Moore’s James Bond wears a Gucci belt and carries a soft-sided weekender bag in The Man with the Golden Gun. Four years later, in Neil Simon’s 1978 rom-com California Suite, the characters not only carry piles of the logo suitcases, they mention the label by name. Fast-forward, and the Gucci style today is very different again, even from its Tom Ford heyday in the ’90s. Under its latest creative director, Alessandro Michele, the vintage maximalism of this next-gen Gucci leads the fashion pack with genderless collections (worn by Harry Styles, for example) and the eccentric, flamboyantly intellectual look that has proven to be catnip to gen-Zers. But it’s still recognizable from its roots.

Young Guccio Gucci was working as a bellhop at London’s Savoy Hotel, when he realized how people of consequence showed off their affluence and good taste through luggage. The choice, he reasoned, conveyed not only status, but also a particular kind of sophisticated, jet-set glamour. That’s what he bet on in 1921 when he opened the first Gucci store in his native Florence.

Nothing on offer in the brand’s centenary year, however, could be more anticipated than Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci (slated for theatrical release on Nov. 24). It is a dramatization of the events leading up to the notorious, true-crime story at the heart of the fashion family when, on a quiet spring morning in 1995, Gucci heir Maurizio (played by Adam Driver) was gunned down in front of his Milan office. A few weeks before, then-creative director Tom Ford’s breakout collection had finally put the house back on the fashion map. The murder capped off years of infighting and power struggles among Guccio’s various descendants (played by Jeremy Irons, Jared Leto and Al Pacino) and Maurizio’s ex-wife Patrizia Reggiani (Lady Gaga), who was later convicted of the crime.

The movie is based on journalist Sara Gay Forden’s 2001 book, The House of Gucci: A Sensational Story of Murder, Madness, Glamour, and Greed. Her account of the rise, fall and eventual revival of Gucci is equal parts sprawling business saga and sordid scandal.

Ford streamlined the Gucci image into a modern, sexy 1990s version of the “flash bordering on vulgarity” that made the company’s fortunes in the ’70s and ’80s. House of Gucci rewinds to the original incarnation, with gobs of chunky, gold jewelry and showy après-ski attire, where big hair, fur, shoulder pads and pounds of mascara were the main events.

Production stills (and viral on-set photos) of Lady Gaga’s status-hungry Patrizia reveal just how perfectly costume designer Janty Yates has nailed the borderline tacky, more-is-more intersection of malice, minks and money. In her heyday, the haughty Italian socialite was known as “Lady Gucci,” but after she was convicted of hiring a hit man to murder her ex-husband through close friend Pina (played by Salma Hayek), the moniker changed to “the Black Widow.” Court psychiatrists deemed Patrizia fit to stand trial, but nevertheless diagnosed a narcissistic personality disorder; in the movie, the excess of her wardrobe (drawn from unlimited access to the Gucci archives) hints at some of that disorder.

The last time we saw this much Gucci on screen was in the period grifter drama American Hustle. Costume designer Michael Wilkinson chose the Italian label deliberately, “to capture the sophistication and glamour of New York in the late 1970s,” he told Harper’s Bazaar in a 2013 interview. In that era, the real Maurizio and Patrizia were a celebrity power couple flitting between Milan and New York.

Bringing Gucci’s story to the screen in House of Gucci is a full-circle moment, because modern Hollywood celebrity, on screen and off, is responsible for Gucci’s success like almost no other brand. Its international profile first hit its stride during “Hollywood on the Tiber,” a term that refers to a period in the ’50s and ’60s when American actors like Ava Gardner and Elizabeth Taylor filmed at Rome’s Cinecittà studios. House of Gucci recreates the pandemonium that ensued when Sophia Loren, played by actress Mădălina Ghenea, visited the Rome store.

Son Aldo’s flair for branding had led to the interlocking double-G monogram logo and other marketable stylings that helped Gucci distinguish itself and transcend its origin as a humble goods and leather shop. Visiting stars snapped by the paparazzi with their Gucci swag helped popularize its signature adornments, including hardware shaped like bridle bits called snaffles and the red-and-green stripe and bamboo handle on handbags (as worn by Bergman in Voyage in Italy).

The logo and branding made it a favourite accessory of international boldface, like Vanessa Redgrave and Princess Grace (and years later, Princess Diana). Soon, Sammy Davis, Jr. was playing rounds with the Rat Pack using his monogrammed Gucci golf bag, and performing in horse-bit loafers customized for tap dancing. Barbra Streisand favoured the slouchy Gucci hobo bag made famous by Jackie O in her New York editor years; Marilyn Monroe’s leather address book was Gucci; and the list goes on. As Guccio predicted, the accessory proved to be conspicuous shorthand for accomplishment.

A version this article appeared in the August/September 2021 issue with the headline “Reel to Real,” p. 84.

RELATED:

Daniel Craig and Other James Bond Stars “Excited” Ahead of Movie Cinema Release of “No Time to Die”