Downsizing: Making the Move From Empty Nest to Solo Digs

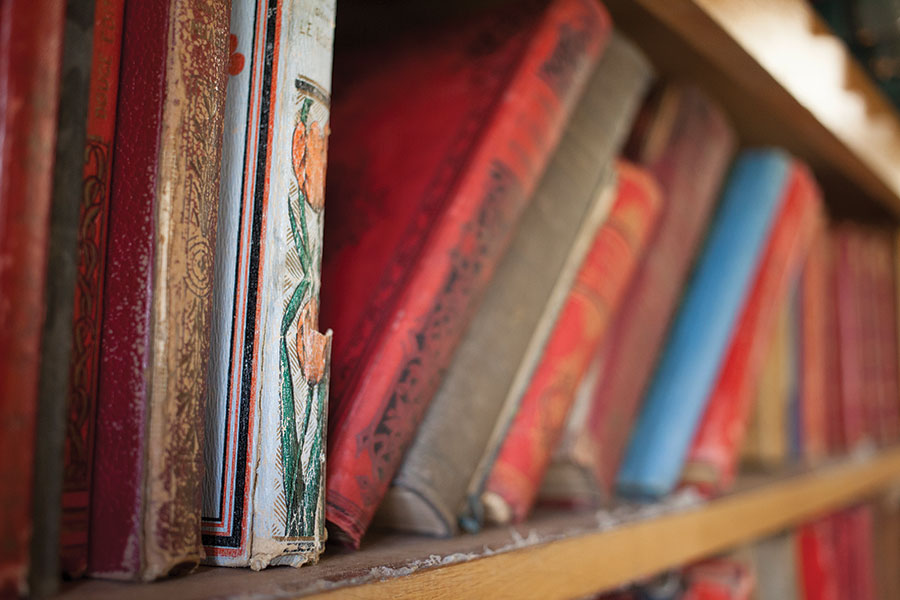

The adventure of exchanging a four-storey house of 37 years for a one-storey, two-bedroom apartment had many chapters, first and foremost, the purging of possessions. Photo: oxygen/Getty Images

Years ago, a friend said casually, “Often, when people decide to downsize and move to smaller quarters, they’re just a little too old for all the decisions and disruption that involves.” I must have stored that remark in the drawer in my unconscious marked Warnings. About a year ago, that drawer popped open.

I didn’t know if I was already too old for the upheaval of downsizing or too young, but I was sure of a few things. One: I was 76, single and in good health. Two: Three years earlier, I had fallen a mere two steps on the stairs in my house and broken my shoulder. Three: My two daughters live in London, U.K., and Vancouver, more than 3,000 kilometres east and west from my house in Toronto, and would not love me for leaving them to clear out my house. Four: I wanted to feather my new nest in my own time and to my own taste, before some change in my health forced me into unplanned and charmless new quarters.

Thus began the adventure of exchanging my four-storey house of 37 years for a one-storey, two-bedroom apartment. There are many chapters to this adventure, including the pros and cons of staging a house for sale and the choice between buying and renting. But the part that absorbed me most – some might say obsessed me – was the purging of my possessions.

My parents loved stuff, from antiques to uncounted tchotchkes, and they passed this on to all five of their children. One of my brothers retired early and started an antiques business. My daughters’ babysitters would open my cupboards and ask why I had so many dishes. To me, this was the oddest question. Didn’t everyone want as many dishes as possible?

So, my house was filled with things, including several thousand books, and they had to go. I began unambitiously last summer, looking through third-floor closets and setting out menageries of stuffed animals, puzzles, barbells, tennis rackets and other once-loved objects on the sidewalk in front of my house, which disappeared almost instantly. There were poignant moments, when I realized the grandchildren were too old for that toy, and no one in the family would look twice at that smashing prom dress, but mostly I felt I was making progress.

It was, alas, a drop in the overflowing bucket and I had to move on to more businesslike attempts to declutter, such as contacting auction houses, consignment shops and my neighbourhood antiques store. I measured, took pictures and tried to answer questions about the provenance of each item, but “brown furniture,” as young people call antiques, is so out of fashion that my efforts met with little success.

I shelved that problem temporarily, because I needed to worry about my books. Everyone will tell you they are the hardest things to dispose of and COVID-19 had exacerbated the problem because libraries and university book sales were not taking donations. My homegrown library, which began with the 50-cent Signet paperbacks of classic novels I read in high school, was especially dear to me. Passing the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves that lined the second-floor hall and two rooms felt like walking through my life as a student, teacher, lecturer, writer and, always, a reader.

How could I part with at least three-quarters of these old friends? As it turned out, I seemed to know instantly which books I would read again, which ones I might finally get around to reading for the first time, and which I would perhaps never read or re-read, but still wanted with me. No doubt I spent too much time dispatching the rest to niche collections and individual book lovers, but in emotional terms, I think I needed to respect my books by finding them the right homes.

I began by giving most of my architecture books to a university and sending four boxes of biographies to a bookish foundation. My Spanish teacher, a bookworm, came and filled a huge Ikea sack. He returned with his wife, and they filled another sack. An almost silent man from a used book and record shop mysteriously titled She Said Boom paid me a few hundred dollars and left with a few boxes. Just as I was running out of time and energy, my contractor said he had a friend who took books to prisons. That sounded almost too good to be true, and the remaining 20 boxes of books left the house. I heard, third hand, that questions about the books’ appropriateness had been raised. (I wonder if the frank histories of personal hygiene I had used as research for my 2007 book, The Dirt on Clean, raised the alarm.) My contractor finally told me, rather vaguely, they had gone “to a good place.” I hope so. Purging has its mysterious side and I had to accept that.

One of the lessons I learned from relinquishing the books was to indulge my instincts, no matter how nonsensical. A pale green book called Bright’s Anglo-Saxon Reader had stood on my shelves for more than 50 years. Even as a graduate student, Anglo-Saxon had not been one of my favourite languages, but the book evoked a particular, precious time in my life. Mr. Bright’s reader, unopened, will go with me to my apartment.

Meanwhile, I returned to liquidating a vast array of Victorian jugs, Mexican ceramics and embroidered hand towels. Most of my family, including five grandchildren, came for “the last Christmas at Nana’s house,” and I invited them to go through the house and pick whatever they wanted. Two grandsons charmed me with their choices: some old inkwells and a not-very-good oil painting of a pitcher and three oranges for the 11-year-old, some fiendish masks from Bhutan for his 12-year-old cousin.

One of my daughters is a minimalist who wanted only two quilts her grandmother had made and a picture of her great-great-grandparents. I was counting on her sister, who inherited the family liking for stuff, and she did not let me down. Her hoard included a brass bed, blanket chest, a full set of china and several pictures. The fact that they will have to be sent to London, at her expense, was a mere fly in the ointment. As I say frequently, everything that leaves my house makes me happy.

Except when it makes me feel guilty. My house has now sold, I’ve found the perfect apartment and I still have a midden of ornaments and family mementoes. In the beginning, the decisions seemed to make themselves, but recently I was left with some heart-rending choices. One of them was my late mother’s statue of Our Lady. Tall and slim, without much figure, the Virgin Mary rests one bare foot on a beautifully painted rose. What kind of daughter banishes her mother’s statue to a yard sale? Apparently, the one who’s writing this article. After moving it in and out of the yard sale pile a few times a day, I finally sold it to a woman who clearly saw its quality. I think my mother would be okay with that.

The sale, with all $600 of the profits going to a Ukrainian relief fund, was my last attempt to place my bits and pieces with people who appreciate them. When she got the announcement, a friend wrote, “Tough to do, or a cleansing blessing?” Both, I would say. But already I feel lighter and freer.

As I learned from purging my books, you have to follow your heart – but judiciously – when decluttering. Among the to-go items on the dining table was an earthenware plate decorated with a woman in Breton dress. My mother hung it on the wall of her kitchen, and so did I, for many years. Suddenly I saw it in my perfect apartment, holding sugar cookies for tea. Before I could think twice, I snatched it up and put it back in my cupboard.

A version this article appeared in the August/September 2022 issue with the headline ‘Memory Lane’, p. 72.

RELATED: