The Rise of the Centenarian: Why More of Us Are Living to 100

Live to 100? The venerable tortoise may not be the only species routinely passing the century mark. Slowly and steadily, the human race is keeping pace. Photo: The Voorhes /Gallery Stock

In this new age of longevity, hardly a week passes without dazzling reports of someone somewhere turning 100. This year’s tally includes New York City’s Lettice Graham, who partied in a Harlem ballroom; Wally Vickberg of Okotoks, Alta., who went four rounds in a boxing ring at his retirement home; and Manette Baillie of Suffolk, England, who raced a Ferrari around a Northamptonshire circuit at 130 miles per hour. Norman Lear, the legendary television producer behind All in the Family, Good Times, Maude and The Jeffersons – who is still working – told The Hollywood Reporter in August that he celebrated simply “by getting up in the morning.”

Making it to the age of 100 is still a storied milestone, but in the 21st century, it’s not the rarefied achievement it used to be. More people are reaching triple digits than ever before. In industrialized countries, the prevalence of centenarians has more than doubled every decade since the 1960s.

While it is still rare to live to 105 — the age at which someone becomes known as a semi-supercentenarian — and rarer still to reach supercentenarian status at age 110 (about one in five million), even the prevalence of these exceptional centenarians is creeping upwards. The United Nations estimates that by 2050 the world will have nearly four million people who are at least a century old. Despite the toll COVID-19 took on older adults, centenarians make up one of the fastest growing segments of the population in Canada, and the world.

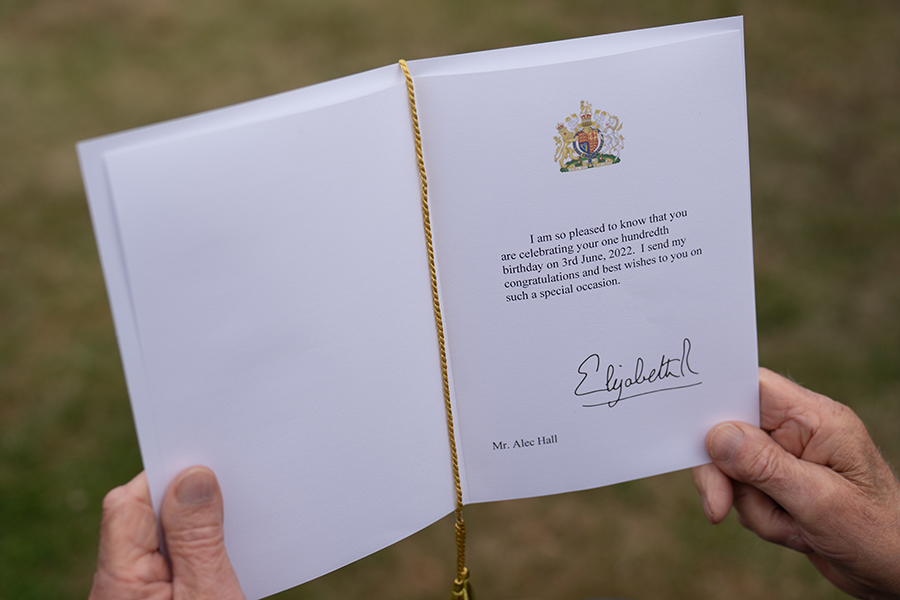

There are signs of it. Hallmark has an expanding selection of birthday cards – “Celebrating 100 wonderful years of you!” ( … and you … and you!). Requests to the Prime Minister’s Office to congratulate Canadians turning 100 climbed to 2,495 last year, an eight per cent rise from 2017. Before her death at age 96, Queen Elizabeth II was sending off so many 100th birthday wishes to her citizens, Buckingham Palace had to hire extra staff to keep up.

All of it is propelling a broad rethink of the 100-year life. Policy makers, economists and city planners are prepping for a demographic revolution that could revamp everything from workplaces to urban spaces. Psychologists and sociologists are pondering the various ways people might reorganize the traditional life stages of education, career and recreation if they have 10 decades to play with. Financial advisers, meanwhile, are trying to design savings plans that will stretch 40 years past retirement.

Yet the centenarian story is not all tiaras and Ferraris. Unless more people hit the century mark in good health — and today, most don’t — the looming burden on health care, community support and the economy could be catastrophic. And who wants to live to a hundred anyway if frail, broke and lonely?

It’s that cold prospect that makes Paul Higgs, a professor of the sociology of aging at University College London, fret publicly over the popular portrayal of people who reach triple digits. “Very old age, if commented upon, is presented as if it were a kind of extreme sports competition. Centenarians are celebrated simply for reaching 100,” Higgs wrote in a 2018 essay in The Conversation, an academic news site. “For many of these people, life can be difficult. … Aged lives of quiet desperation are sadly not rare, nor are most lived in the heroic terms of the marathon-running nonagenarian that hits the news.”

That reality — and the economic imperative that comes with it — has researchers everywhere investigating the minds and bodies of centenarians. PubMed, an online database of life sciences papers, shows the number of studies on centenarians has multiplied more than 10-fold since the 1980s, trying to parse the ingredients that go into the making of a healthy 100-year-old. After all, as Higgs says in a recent interview, “Everyone wants to live to be 100, but no one wants to grow old while doing it.”

Bloom, Fisher and the Hunt for Hundred-Year-Olds

In the early ’90s, when Dr. Thomas Perls was a third-year fellow in geriatrics training at Harvard Medical School, he was assigned to look after two centenarians, and he assumed they would be the sickest patients on his roster: “This idea was quite prevalent at the time — the older you get, the sicker you get.

“The literature indicated that the rate of [getting] Alzheimer’s disease increased at a very fast rate beyond the age of 85 — so one would expect that everyone over the age of 100 would have Alzheimer’s disease.” But then he met Mrs. Bloom and Mr. Fisher.

Bloom was an accomplished pianist who lived on her own and still played at venues around Boston. Perls knew from their conversations she was still mentally sharp, but Bloom impressed him even further when he heard the 101-year-old in concert playing the difficult music of Chopin — and playing it well.

Fisher had been a tailor all his life. The 103-year-old could usually be found in the hospital’s occupational therapy department, not getting treatment, but mending the clothes of the patients there, or teaching others how to mend. “If he wasn’t doing that,” says Perls, “he was robbing the cradle – dating his 85-year-old girlfriend.”

At the time, Perls was looking for a research project and Bloom and Fisher seemed to pose a question worth answering. “I knew I had to find more people to see if these two were a fluke and everyone else [age 100 and up] were as predicted.”

Perls initially focused on eight towns in the Boston area, scanning birthday announcements in the local papers, combing voter registration lists and conducting interviews with the centenarians he found. He discovered that while Bloom and Fisher were not complete anomalies, they were in the minority of successful agers: Only 20 per cent of centenarians were in fairly good shape and free of dementia, while 80 per cent had various health issues.

“So, you might say, ‘Well, what’s so great about that?’” Quite a bit, it turned out. Perls learned that, despite the final result, most centenarians in his study had been functionally independent until about the age of 93 before they declined – which was still beyond average life expectancy, and beyond the age at which most people were expected to have developed dementia.

To find out how these 100-year-olds had managed to markedly delay or escape the diseases of aging, Perls founded the New England Centenarian Study, which, since its inception in 1995, has grown into the longest-running investigation of its kind, with more than 2,000 centenarians and their families enrolled from seven countries, including 107 supercentenarians.

One of its most striking findings is that today, says Perls, now a professor of medicine and geriatrics at the Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, “most people have a shot at making it to 90,” and one in five have the opportunity to get to 100. “That’s a remarkable number.”

The Birkdale Trio

On a sunny afternoon at Birkdale Place, a Revera retirement home in Milton, Ont., more than three centuries’ worth of wisdom is spread across a loveseat and a wingback chair. There’s Marion Newman, who turned 100 in March, Bernard Teague, who joined the centenarian club in July, and Vera Riley, who celebrated her 105th birthday in June. It was quite a party: live music; a local TV crew; Riley’s daughter had come from Alberta; and former Mississauga mayor Hazel McCallion, who turned 101 in February 2022, was among the guests. (McCallion, Revera’s chief elder officer, maintains the key to longevity is waking each day with a plan and a sense of purpose.)

Precisely how long Riley, Newman and Teague have lived at Birkdale, only Newman could remember. “Seven years,” she says. From the get-go, Teague acknowledges, “My memory is terrible.” Riley, in pearl earrings and a jeweled pullover, puts it this way: “My mind is a little bit sticky at 105.”

Riley, trim and still mobile, struggles to recall where she was born in 1917, but within a few moments, the details come back: “Barrow-in-Furness, in England,” she says, happily. “We were very poor, though lots of love, there were four of us. I worked in a sewing factory, making pyjamas. I had a work number, it was No. 9. I remember that — nine is my favourite number.” Her parents lived relatively long lives for the time – her mother, a homemaker, died at 80, and her father, a bus driver, died at 78.

Newman, still quick-witted and mirthful, was one of 15 children born on a farm in Edmonton. She is the only sibling still living. But she had an uncle who lived to 104, and another to 110, so Newman figures she has some years ahead — “I’m only 100!

“I don’t feel any different today than I did when I was young,” she adds. “No matter how old you are, you never think you’re that old.”

Teague, a metal molder who served as a home guard soldier in England during the Second World War, couldn’t recall if longevity runs in his family. But he suspects the recipe for a century-long life needs “a little bit of everything.” Riley says the ingredients are probably different for each person — “What might be good for his long life, might not be good for mine.”

What they do seem to have in common is an almost cheery resilience. All three centenarians describe hardships in their lives, but that afternoon, it casts no shadow on their positive outlooks. Riley lost her husband Frank many years ago, when he was quite young – “He was standing against a wall and just slithered down.” She also lost her son; and her daughter out west lives “way too far away,” she says. “But you just have to take each day as it comes.”

Newman has also outlived her husband and both her children. Still, there’s a joyfulness when she describes how three nieces on her husband’s side are the ones who lured her to Ontario so they could be closer to her: “Isn’t that something?” she says. “One niece comes to see me every night. Last night she was here until 10 o’clock!

“I think the older you get, the more you forget the hardships, you forget about your troubles,” Newman says. “But you know what you think about a lot? You think, ‘Oh, we’re gonna eat! What am I going to eat? What are we having?’” They all laugh hard in agreement at that one.

How One Hundred Became the New Ninety

The first centenarians Perls recruited to his study were born around 1900, when the average life expectancy was about 46 — achingly low, mainly because infant mortality was tragically high. Families could count on losing about a quarter of their children, mostly to infectious diseases, says Perls.

But with improvements to public health — clean water, sanitation, education, better nutrition — and the advent of vaccines and antibiotics, an otherwise doomed quarter of the Greatest Generation not only had a chance to survive infancy and thrive, but also to age.

They lived through the Depression and the Second World War and, as they matured, so did medicine. Screening for early signs of heart disease and cancers, the western world’s big killers, became routine, as did new preventive treatments, such as drugs for high blood pressure, and surgical interventions.

Another boost to longevity came in the late 1970s and early ’80s, says Perls, as the lethal perils of smoking became widely known and more people kicked the habit. With a broader understanding of behaviours that could be bad for the heart, more people started exercising and improving their diets.

For Perls, these factors explain how the prevalence of centenarians in North America has jumped from one in 10,000 people to about one in 5,000. He suspects it will rise further as baby boomers reach their 10th decade, but by how much is unclear. The factors that might predict a century-long life are varied and mysterious.

Who Will Hit a Hundred?

In the world’s five so-called Blue Zones, where people live longer and healthier lives than average and many into their hundreds, longevity is associated with a nourishing mix of good genes, good food, physical activity, family and friends. Yet there are intriguing differences. In Sardinia, Italy, where men are as likely as women to live to 100, and on the Greek island of Icaria, drinking wine is common. But there’s no alcohol consumed by the Seventh Day Adventists of Loma Linda, Calif.

Mostly plant-based diets are common to all the zones (the other two being Okinawa, Japan, and the Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica), as is religion or some form of spirituality. But the New England Centenarian Study has found that being vegetarian does not predict who will live to 100, and neither does religion, money, education or ethnicity. (The centenarians enrolled in the study come from 20 different ethnic backgrounds.)

The tangled links between ethnicity and longevity can be fraught and vary from country to country. In the United States, for example, health care and socio-economic disparities are believed to play a major role in the longevity gap between Black and white people. In January, the Kaiser Family Foundation, an American non-profit, non-partisan health policy analyst organization, reported life expectancy for Black people was 71.8 years compared to 77.6 years for white people. Yet the Office of National Statistics in the U.K. reported in 2020 that data shows Black and other ethnic minorities have longer life expectancies than white people. Black African women had a life expectancy of 88.9 years, and Black African men 83.8 years. For white Britons, life expectancy was 83.1 years for women and 79.7 years for men. People of Asian, Bangladeshi and Black African backgrounds generally lived longest.

Hong Kong, where cancers, cardiovascular disease and car accidents are comparatively low, has recently overtaken Japan as the place with the highest life expectancy. A 2021 report in The Lancet Public Health attributed this to “fewer diseases of poverty while suppressing the diseases of affluence.”

But Japan still holds the top spot as the country with the highest per capita rate of centenarians, a perch experts chalk up partly to low obesity rates and nutrient-rich diets. There are claims of record-high concentrations of centenarians from other parts of the world, including areas in China, South America and the Caribbean, but Perls believes most of these are unsubstantiated.

“I think it’s just to increase tourism,” he says. “There’s been fascination with the idea of living forever, and there can be a tremendous amount of sensationalism associated with that.”

The traits centenarians do have in common in the New England study include not being obese, not having a substantial history of smoking, handling stress well, not being neurotic, being extroverted and being female. About 85 per cent of centenarians are women, and they make up about 90 per cent of those aged 110 and older. Yet centenarian men are usually in better health than their female counterparts.

Lifestyle Vs. Genetics

In British Columbia, the Super Seniors Study led by Angela Brooks-Wilson, a distinguished scientist at BC Cancer, has also delved into the traits of successful agers. The research included 480 women and men between the ages of 85 and 110 who were free of cancer, heart or lung disease, diabetes and dementia. In 2018, Brooks-Wilson reported these super seniors had high physical and mental function, low levels of depression and prolonged fertility. The study also found levels of alcohol consumption were no different than in the control group.

Having a family history of longevity is a strong predictor, but lifestyle choices play a much bigger role than genetics in determining who will become a centenarian. Perls estimates lifestyle factors account for about 70 per cent of longevity to the age of 100, while genes contribute only 30 per cent.

That conclusion is based in part on the surprising finding that most “young centenarians,” aged 100 to 101, says Perls, have just as many age-related disease genes as everyone else. Yet they are somehow resilient, or resistant, to their effects.

Older people who are resilient have illnesses linked to aging, such as heart disease, cancer or dementia, says Perls, “but they seem to deal better with these diseases that other people might die from.” Even more puzzling are those who are resistant and reach 100 without developing these diseases at all.

Beyond the age of 105, the nature-nurture equation flips: The older a centenarian becomes, the bigger role genes play. Lifestyle factors explain just 30 per cent of longevity in people who make it to 110 and beyond, Perls says, while genetics account for 70 per cent.

“What we think becomes very important in these individuals are protective genes,” says Perls. These would be variations of certain genes that shield older centenarians from age-related illnesses entirely, or at least their worst effects.

“As we enrolled even older people, 105 and older, and 110 and older, these folks ended up being the crème de la crème of our sample. The younger centenarians don’t quite do what the people 105 and older do – which is not only greatly delay disability, but also dramatically delay or escape age-related diseases until the very end of their very long lives.”

The New England study has found that 105-year-olds tend to live independently and are cognitively intact until around age 99 or 100. The supercentenarians live independently until about 105, “so they really have very little in the way of age-related diseases.”

Similarly, in Canada, currently home to more than 12,000 centenarians, the Super Seniors Study has reached the same conclusion.

“Our findings support this ‘compression of morbidity,’ theory,” says study leader Brooks-Wilson, who is now dean of the faculty of science at Simon Fraser University. “If you live well and disease-free in your first few decades of life, you are likely to be less sick at the end of your life.” This held true even among two brothers, aged 109 and 110, she says, who remained healthy until very late in life.

Perls believes the chances of living to 110 and beyond depend on carrying the right combination of perhaps as many as 200 different protective genetic variants. “It’s like winning the lottery,” he says.

“It becomes a very exciting proposition if we can find and decipher these protective variants. Then the biological mechanisms that confer protection means we might be able to develop drugs and/or screening strategies … to help other people have resilience or resistance to some of these age-related diseases.”

One clue in solving the genetic mystery may come from women. As the runaway winners of the longevity marathon, women may harbour age-protective genes on the X sex chromosome, of which women have two, and men only one. Another theory posits that women are often iron deficient due to menstruation, but because iron contributes to the development of DNA-damaging oxygen-free radicals, the cells of men age more rapidly.

The study has also found women who have children after the age of 35 or 40 are four times more likely to live to 100 than women who do not. Canada’s Super Seniors Study also discovered exceptional longevity in women was twice as likely if they had children at 40 and older. But Brooks-Wilson stressed this association does not necessarily suggest having a baby, or having a baby later in life, will allow a woman to live longer. Rather, she says, prolonged fertility could simply be an outward sign of a successfully aging biology – something women who do not bear children may also have.

Similarly, Perls suspects it is not so much the act of having children late in life that confers a longevity advantage, but that the ability to do so may reflect a slower aging rate of a woman’s reproductive system — which hints at the existence of genetic variants that may be helping to slow the aging of the body as a whole.

Calculating Your Longevity Odds

With so much yet to be understood about the genetics of aging, Perls stresses that it’s premature for people to spend money on DNA tests to search for longevity genes.

“Much more powerful and enabling is just to look at your family history,” he says. “If you have a history of heart disease or stroke or Alzheimer’s or certain cancers, then you need to be talking with your health-care provider to find out what you need to do to screen for those problems, to either delay them or escape them.”

And since lifestyle choices play the lead role for most people in determining who makes it to 100, Perls recommends those choices be good ones — eating a healthy diet, exercising, not smoking and keeping a healthy weight. “It will be the case that the older you get, the healthier you’ve been.” What’s more, it’s rarely too late to try: “The centenarians in the study have not necessarily always lived healthful lives. We’ve had people who have changed course, although there is always going to be an age at which it is too late.”

But with smoking, Perls says, it is never too late to quit. “The payoff can be huge. … Within a few months, you start to see a really significant improvement in a person’s functionality. After five years, they are practically at the point where they had never smoked, in terms of their

life expectancy.”

In 2002, Perls, now 62, launched a life-expectancy calculator to encourage people to live healthily by showing them — in years — how good habits can increase a lifespan. The free 10-minute test, Living To 100 Life Expectancy Calculator, estimates how old a person will live to be based on answers to 40 questions related to health and family history. About 30,000 people take the test each month, and Perls says it reveals “what they may be doing right or wrong … and people can see how their behaviours make a difference” to their life expectancy. After the calculator was featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show, the server crashed.

Making people aware that how they live now will impact how they age later is critical, he says, because otherwise the road ahead could be an epic struggle, especially as baby boomers — “about 70 million people all aging together” — head toward their eighth decade.

Fighting the Fourth Age

At UCL, Higgs became especially interested in the social dynamics of aging with the realization that, for boomers, retirement no longer meant the end of something, but the beginning. “It had been that you worked and then you retired and then you died, and this all happened in a relatively short period of time,” says Higgs. “But retirement became something to look forward to, not something to dread.”

Known as the “Third Age,” boomers have embraced the post-work period of freedom to try new things, travel, learn, volunteer — and, Higgs adds, to demonstrate how well they can age. “One of the things that exists in various stages of the life course is demonstrating how good you are at various things. And now people are demonstrating how good they are later in life, how they’re able to run marathons in their 80s, and join Masters athletic clubs and swim as fast as younger people.”

Boomers envision a kind of “ageless aging,” he says, which reflects a youth culture that seems itself to be immortal. “They listen to the Rolling Stones still singing about youth rebellion in their 80s.” Yet as the Third Age flourishes, it throws what comes next into “ever sharper and sharper relief” and that’s what Higgs describes as the “Fourth Age” — the late-life period of decline, when physical and mental limitations may lead to dependence. “It’s the stage where people go from living their own lives to being assessed by others,” he says. “Often it’s a shift from a first-person narrative of ‘I want’ to a third-person narrative of ‘That person needs … ’”

Society doesn’t embrace that aspect of aging at all, Higgs says. “It’s feared.” News reports may cheer the 100th birthdays of locals and the famous, especially those performing remarkable age-defying feats, but the majority of those who live extremely long lives are not in this camp. “It’s not discussed, and yet it is implicitly known.”

Indeed, most 100-year-olds are a somewhat invisible group. According to Statistics Canada, almost 60 per cent of centenarians live in nursing homes. “The focus on successful aging creates a barrier among those who have not aged as successfully,” Higgs says. “They are sequestered away by society because nobody really wants to think about that because it threatens the idea of ageless aging.”

As life expectancy continues to rise, and the number of centenarians continues to grow, Higgs feels society has a moral obligation to improve the quality of life of those in the Fourth Age, in part by finding ways to interact with them in everyday life. “Sometimes the only people who have close contact with them are their families, and even that can be done in a very performative way, you know, ‘Once a month, we go and see granny.’”

A 2018 study, based on interviews with 78 centenarians in Germany and published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, found that one in four reported longing for death. Yet nearly 90 per cent of their close family or primary social contacts were unaware of how they felt. Ideally, Higgs says, with longer lives becoming more common, imaginative solutions will arise to ensure the very old remain socially engaged so that “there is more intergenerational exchange.”

At SFU, Brooks-Wilson also sees the aging population as an opportunity. “Kids could help them with so many things, and elders can help kids with their perspective and their self-esteem. They have so much wisdom to share.” The irony is that while the extremely elderly tend to socialize less, most studies have found that socializing is what enables people to reach an extreme old age in the first place – from the Super Seniors Study in B.C. to the Blue Zones.

Back to Birkdale

The three centenarians at Birkdale Place agree that one of the hardest parts of growing old is fending off loneliness, having outlived so many family members and friends. “Time is pretty long, you know, if you sit there all day by yourself,” says Newman, “I don’t know how some people can do it. They go weeks and weeks by themselves. … It’s not easy for anybody to leave their homes,” she adds, “but I’m happy here, it’s easy to make friends. We’re all one big family.”

“Yes, everybody’s friendly,” says Teague. “Companionship makes all the difference, that’s the main thing.” Teague and his late wife used to travel widely, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, and he says he would travel still if he weren’t alone — “I wanted to go to Antarctica, I’m fascinated with that, and I’d like to go — still! I like icebergs and I like the cold. But I haven’t got anybody to go with.”

Would Riley like to travel? “Oh no,” says Riley, shaking her head emphatically — “That’s the end of that!” Then they all roar with laughter again.

The role good humour plays in a long life is also a hot research topic these days. Like laughter, it’s a tricky tonic to measure, but several studies find a strong association between a positive mood and healthy aging. So as Higgs argues, it may well be in society’s best interests to do more to ensure the happiness of 100-year-olds as they rise rapidly in number around the world.

A version this article appeared in the December 2022/January 2023 issue with the headline ‘The Rise of the Centenarian’, p. 54.

RELATED:

Hazel McCallion Turns 101: A Brief Video Tour of the Long Life and Times of Madam Mayor

The World’s Oldest Practising Doctor, 100, Says “Retirement Is the Enemy of Longevity”

Norman Lear Turns 100: 5 Reasons We Love the Hollywood Legend