What Scientists Are Learning About Near-Death Experiences

Adam Tapp photographed four months after his electrocution, ironically at a survivor’s lunch where EMS workers meet people they resuscitated. Photo: Courtesy of Adam Tapp

At 37, Adam Tapp already knows death from both sides. For 16 years, he’s been a paramedic in London, Ont., where he has witnessed his fair share of people shuffling off this mortal coil. And on a February night in 2018, Tapp shuffled off himself.

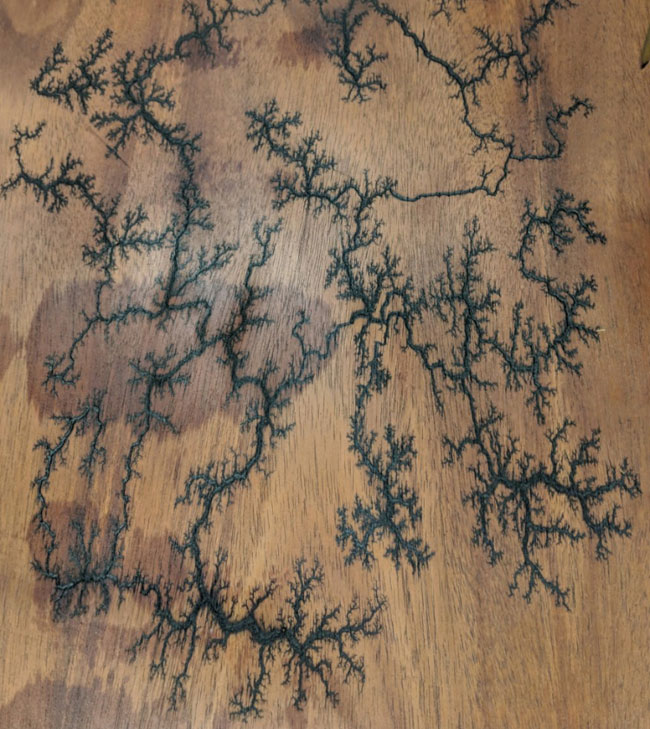

A woodworking hobbyist, he was at home with a friend trying out an etching technique involving a microwave oven transformer. One moment he was chatting, a conductor in each hand; the next, high voltage currents were coursing through his body, burning his flesh and stopping his heart.

“It was quite possibly the most excruciating pain I ever thought imaginable. I remember just being almost dumbfounded in a way, stunned … the current just shut off all my senses. I couldn’t hear anything, I couldn’t see anything, just these vertical, iridescent green bars, like cylinders of various sizes. I remember thinking, ‘I’m being electrocuted. I can’t breathe. I think I’m dying.’”

He was. For 11 and a half minutes, by every clinical definition, Tapp was dead.

He vividly recalls a prolonged sensation of falling, then slipping into a vast alternate space and an altered state of consciousness, one devoid of any sense of self, suffering or anxiety.

“It was just a pure state of absolute tranquility,” he says, “an overwhelming lightness and contentment.”

A Lens on Consciousness

A new international study assessing the personal accounts of 158 people who briefly experienced death has found that, like Tapp, the vast majority describe it in positive terms. The work, published in PLOS ONE in January by researchers at the University of Western Ontario and the University of Liège in Belgium, is part of a growing body of research into near-death experiences.

Known for short as NDEs, they’re considered one of medicine’s most mysterious — and controversial — phenomena. After all, the idea that consciousness can continue without a heartbeat or brain activity raises difficult questions about the biology of “being.” For decades, research in the area was considered fringe science, out there with studies of alien abductions and the paranormal.

Now it’s moving into the mainstream, in part because NDEs offer a unique lens to study consciousness, which is still a fuzzy concept in neuroscience. As medicine gets better at bringing people back from death’s brink, with their return, compelling and eerily similar accounts of glimpsing “the other side” are piling up: feelings of bliss, out-of-body sensations, visions of welcoming figures, tunnels and often a light, brilliant and beckoning.

Scientists tend to agree the recollections are the product of an altered consciousness. What’s unclear is the neurobiology behind it. Some suspect lack of oxygen to the brain triggers hallucinations or that the psychological trauma of dying results in sensations of “depersonalization.” Others suggest that brain activity may continue during death but at levels too low to detect.

No theory, however, fully explains the level of consciousness, hyper awareness and organized recollections people describe following an NDE, which, studies show, remain consistent even decades later.

How much these descriptions are shaped by power of suggestion, through popular culture, Hollywood or religion is a matter of ongoing debate. Even the standard questionnaire researchers use to investigate NDEs has come under scrutiny for encouraging biased responses through loaded questions like, “Did you have a feeling of peace and pleasantness?” or “Did you feel separated from your body?” According to the new study, such questions “may skew recollections.”

To counter this, the Canadian and Belgian research team asked subjects to write a first-person narrative of their near-death encounter and then used an artificial intelligence technique called text mining to analyze the language patterns and keywords in the reports.

“By asking the person to feel free to write about your experience, whatever you want, you have no limits on words, it is a more objective approach,” says study co-author Dr. Andrea Soddu, a particle physicist-turned-neuroscientist at Western’s Brain and Mind Institute. “The point of the text mining is that we wanted to have a method to assess the report that is not biased by the question.”

The subjects, 83 women and 75 men all recruited in Belgium, experienced various near-death events as adults, including heart attacks, comas and traumas. One wrote just 13 words about the experience, while another penned more than 1,500. But nearly all used positive terminology, and the study says their “accounts were highly structured and explicitly narrative with rich emotional components.”

Seeing the Light

The word “light,” for example, was used the most, appearing in 106 reports. Mentions of the word “well” came up in 103 descriptions, followed by the word “see.” The word “tunnel” appeared in 55 accounts, or 34 per cent of the narratives, while “fear” was mentioned in just 19 per cent.

“We were surprised that we didn’t have any religious words among the most frequent words, which is different than what has been reported in the literature,” says Soddu. A 2018 study from Sri Lanka, for instance, found members of monotheistic religions were more likely to report NDEs than Buddhists.

Soddu started out his career as a physicist exploring the mysteries of the universe and still teaches physics at the university. Now he mines the unknowns of human consciousness with brain imaging techniques performed during wakefulness, sleep and under anesthetic. It’s an approach he plans to use to study the neural mechanisms that might give rise to NDEs, and he hopes Tapp, who happens to be a good friend, will be among the subjects.

Although Tapp was not part of the current study, many features of his experience jibe with its findings.

“I Had No Body”

For starters, on the night he was electrocuted, Tapp felt aware of his death and, after the initial surge of agony and the sensation of falling, the pain disappeared. He suddenly felt as if he’d “woken up from a dream in a place he’d always been.” Time had no meaning in that place, which he likens to “outer space, a black void with stars like gas clouds … I felt as if I had no recollection of anything of my life — I wasn’t Adam, I wasn’t dead, I wasn’t a paramedic, I wasn’t anything … I had no body. My entire sense of humanity was extinguished. I was just this raw consciousness floating … seeing from all directions.”

What he saw was a geometric orchestra of fluid shapes around him, “a rhomboid turning into a rectangle, turning into a trapezoid turning into a circle, all simultaneously.” Throughout he was “hyper attuned” to the “lightness” he felt in the absence of stress, fear or anxiety. Then came a wave of connectedness, as if “something was pulling me toward everything … dissolving me into the very fabric of the universe.”

Until, suddenly, a jolt shocked him into feeling as if he was being electrocuted all over again, and then came another jolt. He believes it was two jarring half-second shocks of the defibrillator that helped bring him back to life. “I felt myself being pulled or sucked or something, and then I was vaguely aware of being back in my body. I smelled burned flesh, which would have been my hands, my finger was burned off and my other hand had third- and fourth-degree burns on it. Then I had a weird sensation of being dropped in the space of my consciousness.”

While Tapp was “gone,” a string of coincidences ensured his return. His friend, who had taken a high-voltage safety course three weeks before the accident, managed to shut down the transformer and call out to Tapp’s wife, who happens to be a cardiac nurse. She started CPR immediately, while one of Tapp’s paramedic colleagues was in an ambulance just two blocks away, arriving in time to ventilate and defibrillate him and, at last, raise a pulse.

“He stayed dead for 11 minutes — so that situation would have been very, very bad and he would not be here to report on the situation if he had not been ventilated,” says Soddu.

Near-death Hallucinations

Receiving oxygen while otherwise “dying,” Soddu says, tends to be a common factor among those who have an NDE. He leans toward the theory that neurons starved of oxygen malfunction to produce near-death hallucinations but specifically in the brain’s visual areas at the back of the head.

“Sight is our main way to approach the world, so the regions that are involved in vision are extremely developed for this and require much more oxygenation and much more energy,” says Soddu. When there is a lack of oxygen to the brain, “The visual system may suffer the most or may suffer first. That’s why you hallucinate … and if you suffer in the visual cortex first, you will remember it because you (were) still present in an altered way.”

Soddu also suspects people describe similar near-death experiences because, although “We like to think we’re special,” the human brain reacts the same way to oxygen deprivation. He compares the phenomenon to phantom limb syndrome, where people who lose an arm or leg may still feel pain or sensitivity in the missing limb as the brain tries to compensate for the lack of sensory input.

Tapp, however, doesn’t believe his experience can be explained by lack of oxygen. Instead, he feels it’s the product of another theory that the body produces its own hallucinogenic chemical at the moment of death, resulting in psychedelic effects akin to LSD or mushrooms. It’s a controversial idea but one that’s recently gained some traction among scientists.

Yet whatever the origins of NDEs, most agree the impact is long-lasting.

A Beautiful Experience

“I do believe in general these are positive experiences,” says Soddu. “Hearing Adam talking about this, you feel it. He’s not just making things up, and it’s not just the experience itself. It’s how it affects your life after.”

Tapp spent six hours in a coma after he was resuscitated. But it took him months afterward to feel comfortable in his own skin. He became hyperaware of his breathing and his smell, which he couldn’t stand. His body felt like “a costume” he had put on. The sensation eventually disappeared, but what remained is a calm and serenity he never knew before.

“It was probably one of the most beautiful experiences I’ve ever had. Don’t get me wrong, I love being alive and I love doing things and experiencing happiness and irritation and frustration, and I really don’t even know what stress is anymore. It gives you wonderful peace of mind about what’s relevant and what’s not.”

It’s also changed his attitude toward his life-saving work. “I used to feel bad for people when they were dead,” he says, “but now I think they’re okay. Now it’s more like, ‘Hey, I wonder what you’re doing right now.’”

RELATED:

Martine Rothblatt on Aging, Spirituality, Robots and Living Forever

Want To Live Forever? Biohackers Are Now Focusing On Human Longevity

Learning to Breathe: One Man’s Yoga Journey to Meditative Bliss