No Safe Haven: The Voices That Speak to the Reality of Racism in Canada

Santina Rao seen here at York Deboubt in Halifax, is one of many minorities in Canada who has experienced violence at the hands of police. Photo: Helena Darling

Canada’s reputation as a multicultural idyll masks the reality of racial discrimination.

In toronto, the mother of 29-year-old Regis Korchinski-Paquet, who had Black, Indigenous and Ukrainian heritage, called police for help with a family conflict two days after George Floyd’s May 25 murder in Minneapolis, Minn. The officers went into the apartment and, from the hallway, she heard Regis calling, “Mom, help,” before she fell to her death from the 24th-floor balcony.

In Kinngait, Nunavut, a bystander recorded a video on June 1 of an RCMP officer dooring an allegedly inebriated Inuk man as he drove up to him, knocking him to the ground.

Since the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December, anti-Asian hate crimes have been on the rise across the country, and Vancouver police were investigating 29 cases by the end of May, compared to four in the same time period the year before.

As riots and protests escalated in the United States over Floyd’s death at the hands of four police officers, one of whom knelt on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds, Canadians have joined the chorus of voices calling for an end to racism and violence against Black, Indigenous and other racial minorities, especially police brutality. For them, it reawakened traumatic memories of every encounter they’d ever had with police, clicking through them like a slideshow, thinking, “That could have been me.”

It could have been Santina Rao, a 23-year-old Black mom who was shopping with her two young children at a Halifax Walmart on Jan. 15, when she was stopped and accused of shoplifting. She had a $90 receipt for an electronics purchase with her and a head of lettuce, two lemons and a grapefruit under the stroller that she was going to pay for on the way out. When police asked her for identification and her address, she got defensive because she believed she was being racially profiled. One hit her in the face, according to her account published in the Halifax Examiner, and three more tackled her to the ground. She became even more agitated when she couldn’t see her daughter. That’s when she says the cop who had a knee on her neck said, “Tighten the cuffs on her. She’s a feisty b****.” Rao says she “suffered a broken wrist, concussion and abrasions” in the melee, and one police officer pulled her up by her injured wrist before hauling her off to the police station.

After the Crown dropped all three charges – causing a disturbance, bodily harm to a peace officer and resisting arrest – against Rao on July 7, she planned to register a formal complaint against three police officers and launch a civil action suit against the city and Walmart. “I am worth RESPECT,” Rao writes. “My skin colour does not give others the right to walk all over me and treat me as though my life is second class.”

El Jones, a community activist, journalist and Mount Saint Vincent University professor who covered the story for the Examiner, says Rao’s case is all the more disturbing because it came less than two months after Halifax police chief Dan Kinsella apologized to the Black community for “all those times you were mistreated, victimized and revictimized.” The apology was prompted by an independent report from criminologist Scot Wortley, whose March 2019 findings showed Black Haligonians were six times more likely than whites to be stopped by police officers for street checks. Also known as carding, police use the practice to collect and record everything from ethnicity, gender, age and location on people in case it is relevant to future investigations. The practice was banned in Halifax in October, and the apology came in November.

“[Rao] says they knelt on her neck, like she had abrasions on her neck,” says Jones. “So one of the things she talks about is what happened to George Floyd. They did it to her. And she could have died.”

Jones is tired of repeating herself, tired of having the same conversations about racism and tired of people talking about apologies and reparations, as if that will wipe out Canada’s 200-year history of enslavement, genocide, subjugation, blatant discrimination and knees on the neck. As if it will right a million wrongs.

“Canada loves to act innocent all the time,” she said. “So Canada’s all shocked anew at every new discussion of racism.”

As Montreal author, activist and educator Robyn Maynard, who wrote the 2017 book Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada From Slavery to the Present, told CBC’s Power & Politics in June, one of the reasons racism is so persistent in Canada is because of the perception that we are a safe haven of racial tolerance.

Indeed, two prominent white political pundits – Rex Murphy writing in the National Post and Stockwell Day on CBC’s Power & Politics – argued in June that racism does not exist in Canada, with Day comparing it to the teasing he received as a child who wore glasses.

Canada’s Shame

Once again, Canadians watched the conversation turn from racial profiling and police brutality to a more general subject: is there racism in Canada?

Because of the way we consume news, many of us know the names and stories of Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, but as Toronto activist and journalist Desmond Cole told the CBC in June, “We can’t wait for the Americans in order for us to talk about ourselves.

“We have to stop pivoting from America and then saying, ‘What about Canada,” said Cole, who published The Skin We’re In: A Year of Black Resistance and Power this year. “We have to look into our own communities.”

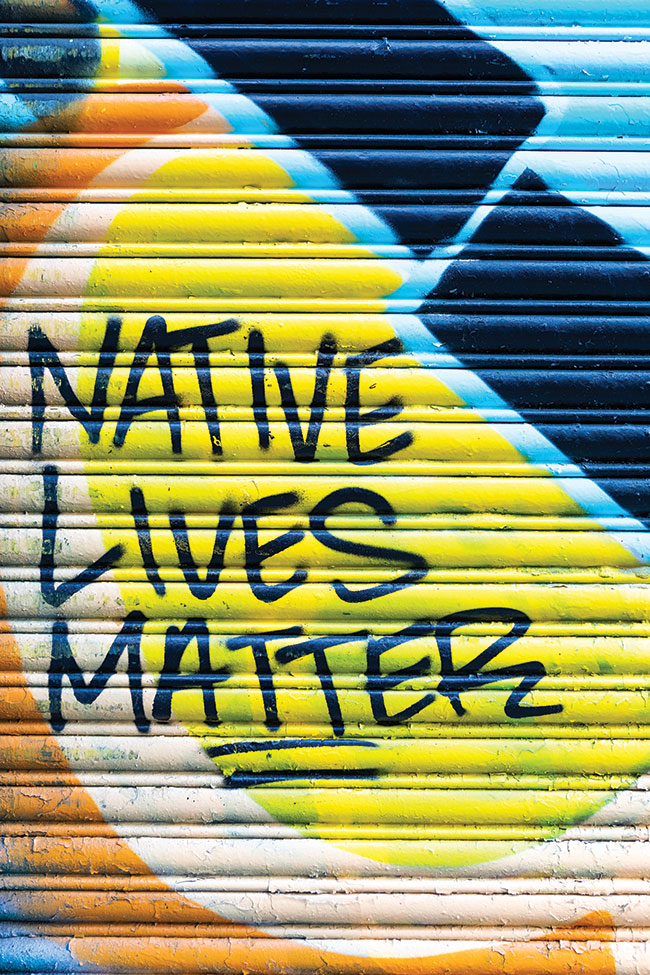

Here are the names, all people of colour, you should know who died in the presence of police this year alone: Jamal Francique in Mississauga, Ont.; Jason Collins in Winnipeg; Regis Korchinski-Paquet in Toronto; Eishia Hudson in Winnipeg; Stewart Kevin Andrews in Winnipeg; D’Andre Campbell in Brampton, Ont., Chantel Moore in Edmundston, N.B., Rodney Levi in Miramichi, N.B.; and Ejaz Ahmed Choudry in Mississauga, Ont.

Levi, a 48-year-old member of the Metepenagiag Mi’kmaq Nation near Miramichi, N.B., was shot and killed by an RCMP officer on June 12, the same day RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki admitted that systemic racism existed in the police force, walking back her public refusal two days before.

Twelve days later, Crown prosecutors in Fort McMurray, Alta., dropped charges of resisting arrest and assaulting an officer against Athabasca Chipewyan chief Allan Adam. Dash-cam video from a RCMP car showed a police officer tackling Adam and punching him in the head outside a casino in March, an incident that started over an expired licence plate.

Racism is a Reality

When the non-profit Canadian Race Relations Foundation commissioned Toronto-based Environics Institute to survey more than 3,000 Canadians in April and May 2019 from all ethnic backgrounds on perceptions of racial discrimination and the state of race relations in Canada, it proved, without a doubt, that racism was a reality in modern Canada.

Not only did more than half of the Black and Indigenous respondents say they had personally experienced racism either regularly or from time to time, but about half of Black and Indigenous people reported others had treated them as less than smart and with suspicion in the past 12 months.

All ethnic groups, including whites, believed Indigenous, Black and South Asian people either often or occasionally experience racism.

“Yes, it exists in Canada is the first [conclusion]. The second is that it’s generally recognized that it happens, even if the full scope of it is not fully appreciated,” said Environics senior associate Keith Neuman. “And there are very, very few Canadians, even white Canadians, who say it’s not a problem at all.”

After collecting age-related data, Neuman said there was no appreciable difference in the perspective of millennials, gen-Xers and baby boomers.

A History of Inaction

The frustration of Canadian protesters comes from the long history of racism and decades of government inaction or lip service.

As a 2017 United Nations Human Rights Council report noted, slavery existed in Canada from the 1500s until it was abolished in 1834. Even though Canada was seen as a safe haven for African-Americans escaping slavery through the Underground Railroad, this country was far from an idyllic sanctuary.

After slavery ended, Black Canadians faced decades of discrimination, not to mention segregation in schools, work places and in housing, as well as in some restaurants and movie theatres.

Viola Desmond, the Nova Scotia woman whose face graces our $10 bill, was arrested and dragged out of a theatre in New Glasgow in handcuffs in 1946 after she dared sit on the main floor, which was reserved for whites, because she was short-sighted and couldn’t see from the balcony. She was fined $26 for “evading” the one-cent difference between a balcony and floor seat and died without any acknowledgement that she was subjected to racial discrimination. The pardon from Nova Scotia’s lieutenant-governor came in 2010 45 years after her death.

The conversation about anti-Black racism, like the one around murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls that prompted a national inquiry and returned a finding of genocide in June 2019, has been going on for years and makes headlines every time there is another senseless death, another hate crime, another blatant instance of racism.

Black Canadians are still waiting for the federal government’s response to the UN report, which had dozens of recommendations, including an apology to

Canadians of African descent and paying reparations “for enslavement and historical injustices.”

On June 2, Trudeau pledged to do better in the House of Commons, acknowledging he “has made mistakes in the past” – an oblique reference to pictures that surfaced during the 2019 election showing him in blackface and brownface – and saying everyone who has felt the oppressive weight of racism deserves better.

He said the “facts” are “anti-Black racism is real, unconscious bias is real, systemic discrimination is real. For millions of Canadians, it is their daily lived reality, and the pain and damage it causes is real, too.”

But when reporters asked him twice if he would address the UN report’s recommendations, he didn’t answer. Meanwhile, a national action plan on murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls promised by the federal government won’t be implemented in June as promised due to the coronavirus pandemic, even though many of its 231 recommendations are considered urgent by the report’s authors.

Jones has a list of things the prime minister could do to improve the lives of Black and Indigenous people: suspend the Canada-U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement, which closes the door to refugee claimants from the U.S. and sends them back to a country where they are detained and, likely, deported; and scrap minimum sentences. She points out that without minimum sentences, judges could consider extenuating circumstances and would have “the discretion not to incarcerate people.”

At the top of her list is removing Public Safety Minister Bill Blair from cabinet. As Toronto’s chief of police, he presided over the force when the Toronto Star revealed in 2013 that its practice of carding meant Black people were 17 times more likely than white to be stopped and asked for identification and questioned. In 2015, the city hired Mark Saunders, a Black man who was a deputy chief, to replace Blair in an effort to move past the carding era, but Saunders was vilified for defending the practice when it came to gang members. He announced his retirement on July 31, eight months before his contract expired, “to put family first.”

Blair was also in charge when Black Lives Matter Toronto stopped the 2016 Pride Parade – which Trudeau was hosting – over what they saw as anti-Black racism in the LGBTQ community. One of their demands was a ban on police marching in the parade.

“If Trudeau cared about policing and anti-Black racism, wouldn’t Bill Blair be gone from cabinet?” Jones asks. After Trudeau attended an

anti-racism protest in Ottawa on June 5 and took a knee, wearing a face mask to protect against COVID-19, Jones saw it as “performative,” an empty gesture

from the man who holds the reins of power in his hands. She says it was an example of the “politics

of recognition,” where racism is acknowledged, but there is no action.

“If people thought about it for five seconds, they would see how ludicrous it is. Why is Trudeau showing up at a protest? You’re in charge of the country. I have to show up to a protest because I don’t have any institutional power. The only institutional power I have is getting my body in the streets.”

Defunding Police

On both sides of the border, one of the biggest demands is for cities to take money away from police budgets and give it to communities that are disproportionately affected by police surveillance and brutality and are historically underserved when it comes to social services.

In Toronto, Cole suggested the mayor could take the $1.2 billion police budget and use it to fund people trained in de-escalating tense confrontations with law enforcement, instead of using it to pay $120,000 salaries to officers with guns, batons and tear gas.

Although Toronto City Council defeated a motion in June to cut the police budget by 10 per cent, it passed one from Mayor John Tory that includes incremental changes to policing, such as the “creation of non-police–led response to calls which do not involve weapons or violence, such as those involving individuals experiencing mental health crises and where a police response is not necessary.”

And in Halifax, Jones has been attending police board meetings since January and was the first to flag the almost $400,000 armoured vehicle police wanted to buy. City council scrapped the purchase in June and reallocated the money to municipal offices that work on diversity and inclusion, public safety and anti-Black racism. But police are asking for a $90 million increase this year, almost a million more than last year, or one-10th the city’s budget.

Racist Thoughts

Why and how racism happens is what interests Lilian Ma, the executive director of the Canadian Race Relations Foundation, a charitable educational organization set up by the federal government and the National Association of Japanese Canadians in 1988 as part of the deal to redress Japanese Canadians who were persecuted and mistreated during the Second World War.

“I like to study the phenomenon of racism itself, as something that people can acquire without realizing,” said Ma, who got her PhD in chemistry before switching to law school and subsequently working for the Ontario Landlord and Tenant Board, the Ontario Human Rights Council and Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Board.

What underlies it is something called implicit or unconscious bias, which is a view and opinion that we’re not even aware we have. Ma says it comes from the stories that societies tell about themselves and that people tell their children. The human brain develops shortcuts in thinking so we can make snap decisions without expending a lot of time and energy. It gave us an evolutionary advantage because it allowed us to associate, say, tigers with danger and avoid all tigers.

The history of white colonization is one of conquering and subjugating other races and imposing European values on them, like Christianity, for example, or the English language, because they believed they were civilized, and everyone else was not.

“If you grow up in a society that’s already had a prejudice before, it just keeps on transferring to the younger generation,” said Ma.

Training the Brain

Ma, who is 74, grew up in Hong Kong, where she didn’t see a lot of white or Black people, so she has tried to train her brain to override any implicit bias with a mantra: “White people are good, white people are good,” she tells herself and “Black people are good, Black people are good.”

She pointed out that in 1950, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) put out a statement prompted in part by the extermination of more than six million Jews in the Holocaust, saying that race is not a biological phenomenon but a social construct. Yet racism persists.

Ma said the key is education and, to that end, there are many lists of resources that have been published lately on social media, including a long, thoughtful Twitter thread by The Secret Life of Canada podcasters Leah-Simone Bowen and Falen Johnson.

The race relations foundation has five modules on its website, as well as a digital guide for teachers and students called Doing the Right Thing. It is now working on a travelling bilingual exhibit called The Science of Racism, which will explore the latest research on the psychological and neurological underpinnings of unconscious biases.

“You have to learn,” said Ma. “We use opportunities like this to get momentum to make changes, and one of the big changes is in education.”

A version of this article appeared in the Sept/Oct 2020 issue with the headline “No Safe Haven,” p. 72.

RELATED:

Hal Johnson Reveals His Experience With Racism in Media and How it Sparked “Body Break”

Racism in Canada: Reputation as Multicultural Idyll Masks Reality of Discrimination

Meet the Entrepreneurs Promoting Diversity in the Beauty Industry Through Their Style and Work