As Prince Harry Prepares to Release His Memoir ‘Spare,’ Looking at the Complexities of Sibling Rivalry And How to Move Beyond It

Prince Harry and Prince William watch a flypast to mark the centenary of the Royal Air Force from the balcony of Buckingham Palace, July 10, 2018. Photo: Max Mumby/Indigo/Getty Images

When Toronto family counselor Alyson Schafer found out that Prince Harry’s forthcoming memoir is titled Spare, she laughed outright.

It’s funny, she said, because it’s so obvious. “It speaks to being the second of two, living in the shadow of the older sibling.”

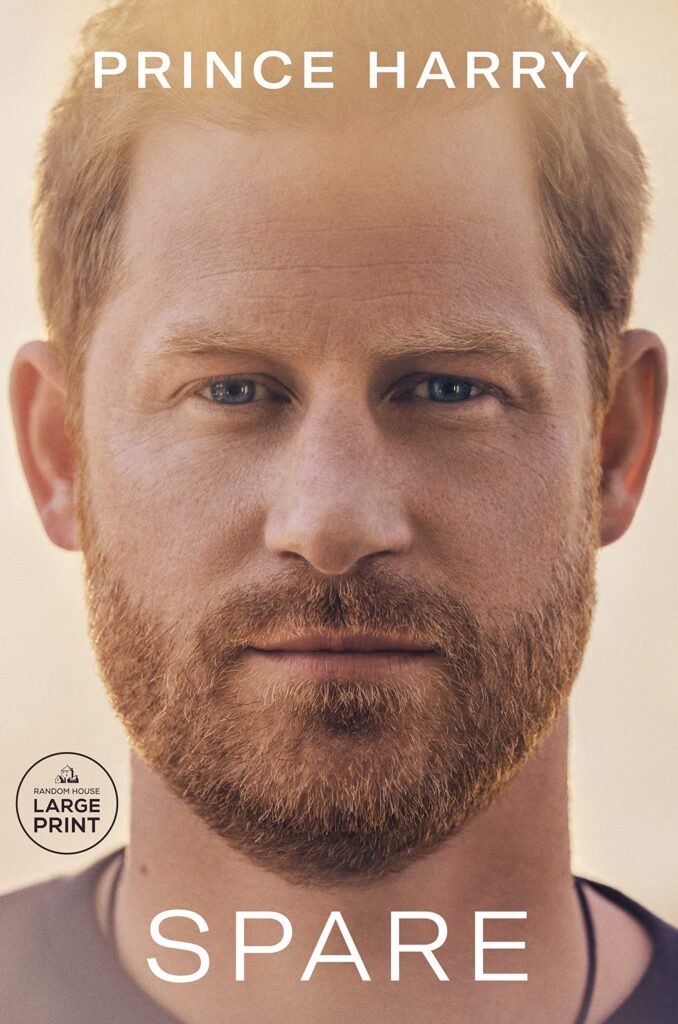

Because it’s the Royal Family, the sibling rivalry is writ large. Literally. The word “spare” is spelled out in huge letters on the book cover under a close-up, unsmiling portrait of the aggrieved prince.

It’s a familiar story, especially in societies where primogeniture — the winner-takes-all law — passes the wealth, the estate and the title to the first-born. The second born gets little to nothing unless his older sibling dies or abdicates. Hence, the “heir and the spare.” Traditionally, the second son had to make his own way in the world, often emigrating to a colony — or, more recently, California.

In the case of the Windsor brothers, it’s not just a piece of land with a country pile or a tidy fortune that’s going to the oldest. It’s the British throne and all the status, largesse, soft power, courtiers and security that come with it.

William gets it all. Harry gets, well, an unimportant dukedom and a lot of criticism, even hate, from his compatriots for leaving Britain to make his own way in the world and for complaining about his family and how poorly he’s been treated.

But even in commoner families without a throne (and property worth 15 billion pound sterling — C$22.9 billion — including much of the finest real estate in London, plus an assortment of palaces to pass on), even among ordinary adults and aging siblings, there’s very often rivalry and rancour about who got the best deal in family, the most affection or regard or favour.

“There’s a perception that we’re competing for our parents’ resources, time and attention,” explains Schafer, author of Honey, I Wrecked the Kids. “Our sense of security is highly determined by whether we think another sibling is going to take some of our parents’ love, time and attention.”

We worry, she says, that we’re getting “the fuzzy end of the lollipop.”

Birth order, in families without crowns or titles to be inherited, isn’t necessarily a factor, according to Schafer. Rather, it’s about the family constellation.

“There are so many different factors including gender and how many years there are between children. With two boys close in age, there’s more competition.”

Sibling rivalry begins at a very young age, Schafer explains, because, as in any social system — for example, a bee colony where there’s a queen, pollinators and workers — “we’re tasked with trying to find our role, significance and importance. And our first social group is the family.”

Even if parents don’t encourage competition by comparing kids, or assigning them roles as “the smart one,” or “the athletic one” or “the naughty one,” siblings will try to carve out their own roles, Schafer says.

A child who feels less valuable in the family (Harry obviously knew he was less valuable very early on) may even create situations to back up that feeling.

For example, “a person who thinks their wishes are never considered in the family will purposely take a position that’s contrary to what everyone else in the family wants so they can say, ‘See, I never get my way.’”

Sibling Rivalry in Adulthood

But shouldn’t we grow out of this insecurity and petulance as we mature?

We should; but very often, we don’t. Even in middle age and beyond. (Personal disclosure: my much older brother, in his 80s, is still convinced that I was the most cherished child because I was the baby girl. I, on the other hand, remain convinced that he was the most cherished because he was the first-born and a boy. We still argue about this, mostly jokingly but with a lingering residue of resentment.)

“In about the first five years of life, our basic core beliefs, personality and unique way of going through the world get established,” suggests Schafer. “And that’s the blueprint for the rest of our lives” — the stories we tell ourselves about who we are.

Schafer offers an example in her own life. “I’m the youngest and the only girl in my family and even though I’m a success out in the world, when I go back home, I’m still the little sister.”

Recently, she says, “I had to cancel an engagement with a girlfriend to go to a spa because of my exposure to COVID. Then, when I had to cancel a second time because of a second exposure, I had the feeling that my friend didn’t believe me. I felt like a little girl. That powerless feeling, feeling smaller, is still in there and it’s deep.”

Overcoming these deep feelings that don’t serve us well as adults can be a challenge. It’s often why people go to counselling, says Schafer.

“Many people are liberated from these feelings when they’re outside of the family but when they come back into the family, they snap right back.”

In counselling sessions, Schafer asks clients to talk about growing up and how they knew they were or were not significant and important in the family. She might say, “I can see why you came to the conclusion of being less valued.”

But then she’ll advise, “You can still mourn your pain, understand where it came from and how it served you but try to loosen the grasp of that pull. Figure out how you can be empowered to see things in a different way and not let it have the same stranglehold. Craft some little experimentation in changing the narrative.”

Nevertheless, she adds, “Depending on the toxicity of the family, in families that are really awful and overtly harmful, the healthiest route ahead might be to carve away what’s rotten, to cauterize the emotional pain, to say goodbye and get on with healing and growth outside of the family.”

Letting It Go

She also encourages clients to “understand that everybody has a subjective reality and really didn‘t get raised in the same family by the same parents. Everybody experienced it differently.”

Schafer offers these tips for overcoming any lingering sibling rivalry and the roles that were assigned or self-assigned growing up:

- At family holiday occasions or celebrations, imagine the event as a comedic special. Who would you cast as each member of the family?

- Remember that it’s just a few days and the majority of your life and validation can come from others rather than members of your nuclear family now that you’re an adult

- Why let someone else ruin your good day even if it’s your brother?

- Share the stories of growing up and have a laugh about the subjectivity of it

- Keep in mind that everybody in the family was doing the best they could do with the life they came from; your parents were products of their upbringing

- Move on from your private logic and subjective stories and adjust your thinking to be more in line with common sense and compassion

- As in all things, recognize and accept that you can’t control the situation but you can control your attitude to it.

- And finally, says Schafer, “You just could not care. How about that? Let it go. That can be very liberating”

RELATED:

Prince Harry’s Memoir ‘Spare’ Will Be Published in January 2023

Prince William “Cannot Forgive” Prince Harry, According to ‘The New Royals’ Author Katie Nicholl