Baseball Historian Gary Sarnoff Talks Opening Day, Rule Changes and His New Book About the 1924 World Series

Fred Lindstrom of the New York Giants bats as catcher Muddy Ruel of the Washington Senators sets up behind home plate during a game in the 1924 World Series at the Polo Grounds in New York City. Photo: Bruce Bennett Studios via Getty Images Studios/Getty Images

The warm spring weather means one thing to baseball fans — opening day is here. It’s finally time to play ball!

Baseball fans always celebrate the new season, revelling in the sense of optimism that comes with the first pitch. Maybe this will be the year that the Toronto Blue Jays will finally break their 31-year drought and win the World Series. Or, at the very least, maybe they can put their recent post-season misery behind them and win a playoff series for the first time since 2016.

It’s a long road to the World Series and teams that make it to the top must rely on talent, hard work and, perhaps most importantly, good luck.

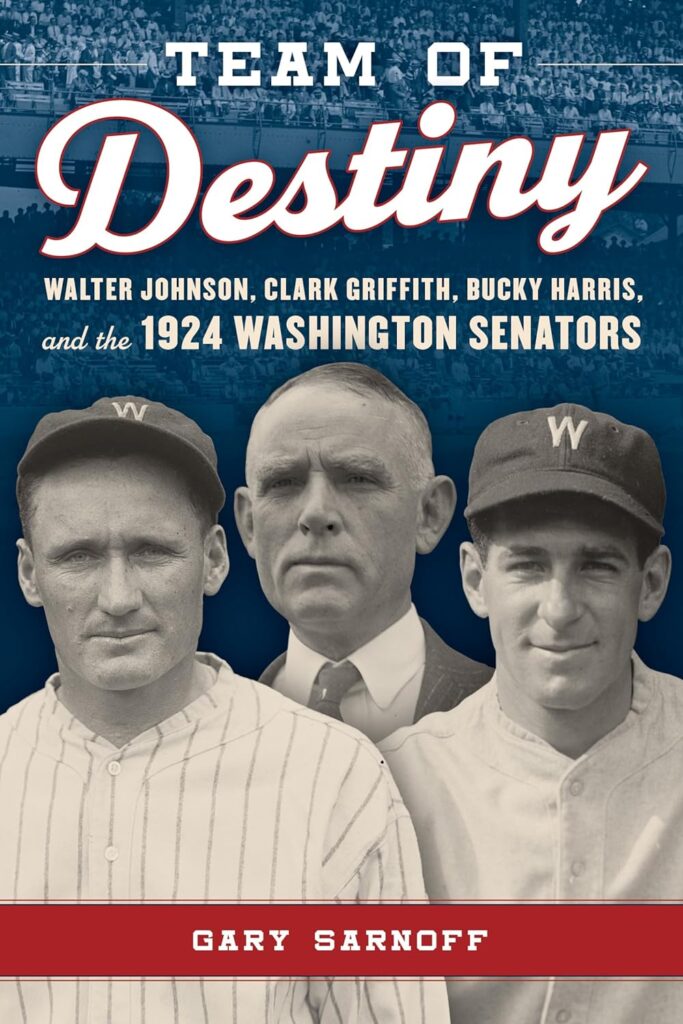

Finding that elusive winning alchemy always produces a fascinating tale, like the one baseball author and historian Gary Sarnoff recounts in his latest book: .

His book gets up close with the personalities that captured the hearts of fans as they went on a glorious ride to the top of the baseball world, and the astounding luck that accompanied them along the way. Readers will be fascinated at how different the sport was while, at the same time, surprised at how little the game, players and fans have changed over the years.

So, to help us get ready for the 2024 baseball season, and to take us back to that magical events from a century ago, Peter Muggeridge spoke to Sarnoff by telephone in Arlington, VA.

PETER MUGGERIDGE: I’m guessing you’re one of those people who gets very excited about opening day?

GARY SARNOFF: Oh yeah. I’m always looking forward to baseball season. Opening day means warmer weather is coming.

PM: It’s always a special time. What does opening day mean to baseball fans?

GS: It’s the start of a new season, meaning there’s always hope for your team, no matter how badly we did the previous season or how bad we’re expected to be for the coming season. It’s about getting excited about going to ball games, to watch your team going to the ballpark. It means springtime, warmer weather is coming and so is our favourite sport.

PM: Baseball has always leaned on its traditions – celebrating its past stars and its history. But do you think that some of the new rules have perhaps broken the link to the past? I’m speaking specifically about the pitch clock.

GS: I think the pitch clock is a good idea because it speeds up the game. Games have gotten longer and longer and I think if you want to keep the interest, the excitement, if you want families to bring the kids to the games, I think it’s a good idea to do whatever you can to speed up the game. So I don’t think that rule in particular will sever the game from the past.

PM: As a baseball fan, would you consider yourself a purist? [Purists are generally sceptical of rule changes and attempts to modernize the game.]

GS: Yeah, I’m more of a purist. I like rules to stay the way they always have been. The pitch clock is a good idea, but I don’t like the extra innings, where you put the extra runner on second base. I don’t care for that.

PM: I’m always hearing people say that baseball is an old person’s game. That it’s out of step with the times and needs an overhaul to make it relevant to younger generations. Do you feel the game needs to radically change to maintain its popularity?

GS: No, I don’t think so. Baseball is baseball and it’s always drawn fans throughout the U.S., throughout Canada and throughout the world. It’s a great game, always has been. And I think kids will continue to play and fans will continue to go to the ballpark – it’s still the American pastime! There’s a lot of excitement, a lot of thrills in baseball. It doesn’t have to be changed.

PM: We’re seeing in all sports that certain teams with unlimited budgets are able to dominate their leagues every year. In baseball, teams like the L.A. Dodgers, the New York Yankees and the Boston Red Sox seem to have an unfair financial advantage over smaller-market teams. Is MLB in danger of creating a two-tier league between the haves and the have-nots?

GS: Some people think they have an unfair advantage. But there’s just a lot more to the game of baseball, a lot more to winning than just having the money. You need to have a winning organization too. There’s a lot that goes into winning the championship, there’s team chemistry and having the right players. The Yankees aren’t expected to be good this year. Same thing with the New York Mets, the Chicago Cubs and the L.A. Angels – these big-market teams are not very good even though they have the money.

PM: The Dodgers have the phenomenal pitcher/outfielder Shohei Ohtani, who seems to me to be a player who could have starred in any era. As a baseball historian, where would you say he ranks among the all-timers?

GS: Right now I would say he’s one of the greats. He probably could have played any era and would have been great in any era he played in. He can do everything well. He’s just a great talent and so exciting and fun to watch.

PM: Ohtani is definitely a must-see player – whether he’s on tv or, even better, in the ballpark.

GS: Yeah, my season-ticket group had its ticket draft last week and, lo and behold, the games against the Dodgers were sold out. Wherever he goes, he’s gonna pack them in, no doubt about it.

PM: Let’s go back to 1924, a hundred years ago, to the time when your book is set. Can you give readers a bit of a teaser on what can expect in this book?

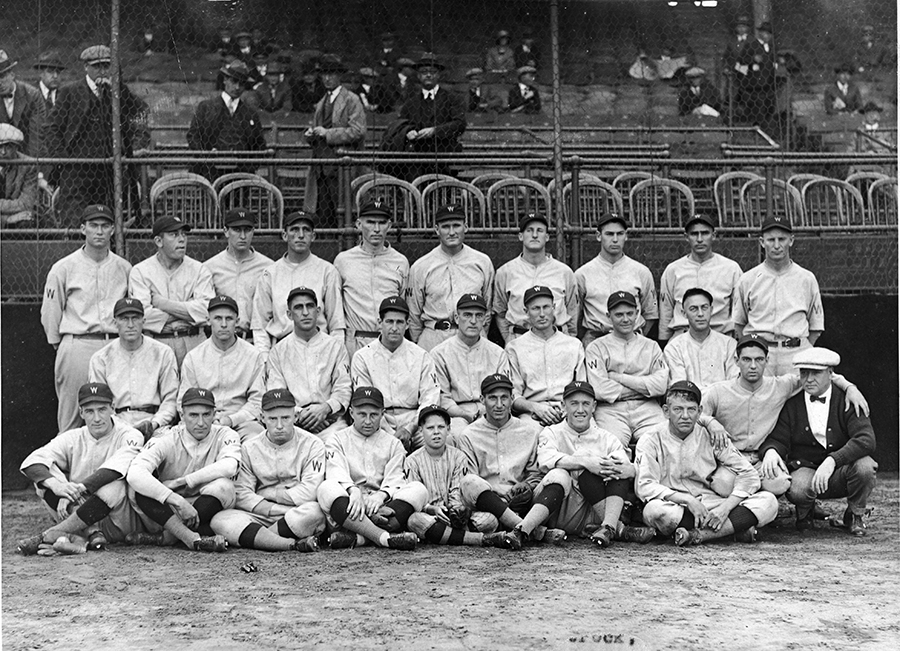

GS: It’s a wonderful story about an underdog that had never won anything prior to 1924. The Washington Senators had a checkered past, had very few winning seasons, never really were in contention to ever win a pennant. It was a team that nobody expected to do well heading into the 1924 season. But it all came together that year. They had, they had a good team, they had a good roster, but nobody really knew much about these players, and nobody expected them to win.

PM: Underdog stories always appeal to sports fans.

GS: I think they’ll enjoy reading about how the Senators were able to become a winning team almost all overnight and take on the Yankees and win the American League. Then go on to win the World Series against the great New York Giants, a powerful team that had seven Hall of Famers in its lineup.

PM: It was one of the biggest upsets in baseball history. Can you point to any recent examples?

GS: The 1969 New York Mets were a team just like that. A team that had never won, a team that was laughed at, a team that had seven or eight straight seasons of losing baseball. And all of a sudden in 1969, you know, win their division, win the National League pennant and then the World Series.

PM: All of the players from that 1924 team are dead now. How did you research your book?

GS: I went through the newspapers, mostly the Washington newspapers, from the first day of the year to the last game of the 1924 World Series. I’ve read a lot of books about the Washington Senators, and the Bartlett Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown is a wonderful resource.

PM: Did any personalities stand out?

GS: Bucky Harris who’s a fiery competitive ball player and a fiery manager. As far as humour goes, there was Al Schacht, the Senators third-base coach who was known as baseball’s clown prince. He was such a comical baseball player, very entertaining. He was a joy to learn about.

PM: Can you explain to the modern sports fan just how big baseball was in the 1920s? How it dominated the sports landscape?

GS: Baseball was pretty much the only sport. Professional football was in its infancy. The NHL was in its infancy. There was no NBA. Boxing was popular but baseball was pretty much the only major sport at that time. Its popularity had a lot to do with Babe Ruth. Everyone wanted to see Babe Ruth hit a home run.

PM: Back then, if you couldn’t go to the game, how would you follow it?

GS: Most of the fans relied on the newspapers. There were also electronic scoreboards stationed in front of newspaper buildings and at street corners. These would give you the play-by-play of every baseball game through lightbulb signals. So if the batter got a base hit – say, a single – a bulb under the word “single” would light up. If it was a home run, another bulb would light up. People gathered by the thousands around those scoreboards.

PM: Were the games being broadcast on the radio yet?

GS: Radio stations covered baseball games in the World Series but they didn’t have a play-by-play announcer. They would say “ball one” or “strike one” or “base hit.” There’s a great story about Earl McNeely, the Washington Senators rookie centre fielder who happened to knock in the winning run in game seven of the 1924 World Series. His parents were listening to the radio account all the way out in Oakland, Calif. The first announcement they heard was: “foul ball, strike one.” Then they had to wait out a pause, and then the next announcement was: “Washington wins the World Series!” Then there was another pause, and then the next account: “Earl McNeely singles, Muddy Ruel scores.” The McNeelys weren’t sure what had happened so they actually had to call the newspapers and ask whether what they heard was true. You couldn’t really rely on radio back then.

PM: The suspense must have been deadly.

GS: Right. Another thing too about listening to radio back then was that only one person could listen at a time. So what would happen is that someone in the McNeely family would put on the radio headphones and listen to each pitch, and then would announce it to the rest of the family.

PM: Fantastic, Gary, I could listen to these stories all day. Thanks for getting us in the mood for the baseball season.

RELATED

Remembering Hank Aaron: Legendary Baseball Star and True Home-Run King Passes Away at 86

Remembering Legendary Baseball Broadcaster Vin Scully With 5 of His Most Memorable Calls