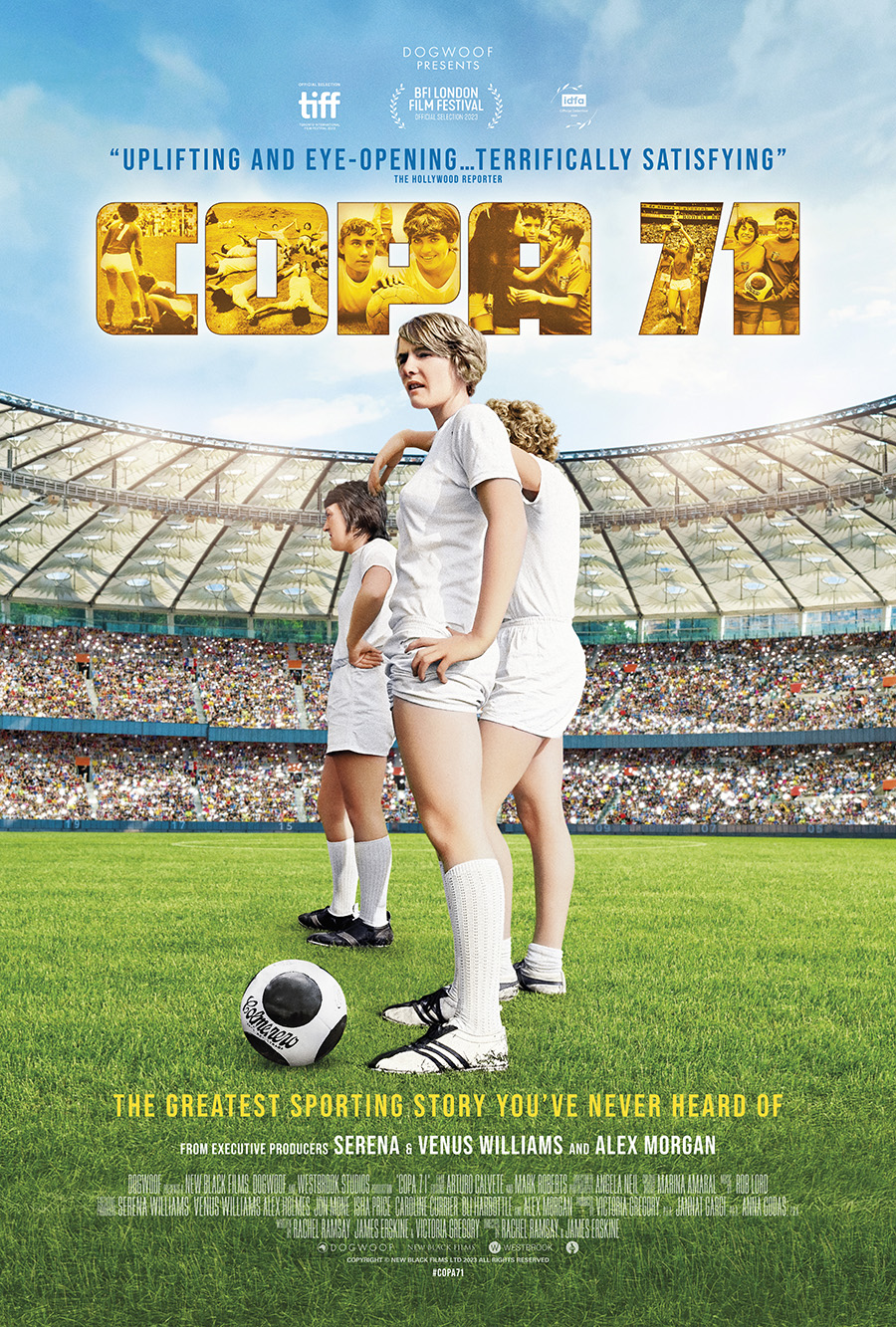

New ‘COPA 71’ Documentary Celebrates the Greatest Women’s Sporting Event the World Forgot

A member of Denmark's team celebrates with the trophy after winning the Women's World Cup in 1971 in front of a record crowd in Mexico City. Photo: © New Black Films ltd / Mirrorpix / Colour Artist Marina Amaral

Quick – name the most-attended women’s sporting event in history.

No, it’s not the recent Professional Women’s Hockey League match between Toronto and Montreal that attracted over 19,000 people to Scotiabank Arena in February of this year – though that set a record for women’s hockey.

Nor is it the achievement realized last August by the University of Nebraska when “92,003 fans watched the five-time NCAA champion Nebraska volleyball team beat Omaha 3-0,” as reported by ESPN – though that, too was impressive.

In fact, it’s something of a trick question. Until the engaging new documentary Copa 71 – which premiered last fall at TIFF and is expanding across Canada on March 8 (appropriately, International Women’s Day) – almost no one knew the answer.

As the film reveals, the highest attended women’s sporting event in history occurred in August 1971. That’s when soccer teams from Denmark and Mexico faced off in front of 100,000-plus ecstatic fans at Mexico City’s Azteca Stadium, having bested teams from England, Argentina, France, and Italy in semi-final matches that were also enthusiastically received by the public and obsessively chronicled by the Mexican press. Denmark won the game, and the championship, 3-0.

Yet the pioneering, unofficial Women’s World Cup was dismissed both by FIFA, the sport’s governing body, and by domestic soccer associations around the world because the game was deemed unseemly for women – unless, of course, it was viewed through the lens of athletic young babes in “hot pants,” one actual angle of the event’s marketing campaign.

In hyping the match, Jaime De Haro, head of the organizing committee behind the Women’s World Cup, told the New York Times in a June 1971 interview that “Women who play soccer are not muscular monstrosities but generally pretty girls.” Sigh.

Not to be outdone in the knuckle-dragger department, the Times regrettably headlined the piece, “Soccer Goes Sexy South of Border.”

The match’s status as a World Cup is still not recognized by FIFA; the first officially sanctioned Women’s World Cup happened in 1991. And despite the massive, aforementioned press coverage of the event in Mexico, where each team had their own dedicated news photographer, once the matches were over no one talked about them. This even though they had shown decisively that women’s sport was every bit as exciting – and bankable, if promoted properly – as men’s.

Indeed, were it not for British filmmakers Rachel Ramsay and James Erskine – backed by tennis greats Serena and Venus Williams, and American FIFA World Cup winner and Olympic gold medalist Alex Morgan as executive producers – the Copa 71 story might have remained forgotten.

“This was a huge team effort, and we were looking all over the world for footage either of the tournament itself or football being played at that time,” Ramsay says during a call from London, adding that the Williams sisters got involved via Westbrook Studios, the media company launched in 2019 by Jada Pinkett Smith, Will Smith, and their partners.

“They had just made King Richard and they knew the Williams sisters were interested in backing female sports films,” she says. “This was a perfect fit.”

Ramsay continues: “In addition to the match in Mexico, we really wanted to highlight this subculture of women playing all over the world. We knew it had happened; we were talking to women who had played all over the world. But finding anyone who had thought it worthwhile to film anything about it, and to keep [that footage] safe, was incredibly difficult.”

In addition to thrilling and previously unseen footage of the matches, Copa 71 features contemporary, first-person interviews with athletes from each of the teams that competed at Azteca Stadium, whose towering achievements went unheralded for decades.

Both inspiring and slightly heartbreaking, the women’s recollections form the core of the film, which also charts their respective lead-ups to Mexico as well as diving deep into the history of women’s soccer/football.

As historian David Goldblatt notes, in 1917 there were 100 female football clubs in England, but women were banned from playing in 1921 for “health reasons.” Today, women’s football is the fastest growing sport on the planet, notes co-director Erskine from Los Angeles.

He explains that the idea for the film came from one of its producers, Victoria Gregory. “Just before the pandemic, she heard one of the players from the English team speaking on the radio about this tournament she’d never heard of.

“She knew we’d done films about football in the past,” he added – notably 2019’s six-part documentary This Is Football, chronicling the game’s global reach, and 2020’s The End of the Storm, following the Liverpool Football Club. “So, Victoria called to ask if we had heard of it. We hadn’t. We began digging.”

As the film observes, a year prior to the Women’s World Cup, Mexico’s enormous Azteca Stadium hosted the 1970 World Cup Final. Two years before that, it hosted the Summer Olympics. And then … crickets. Something spectacular needed to happen again to fill those many empty seats.

While the idea of staging an international women’s soccer competition was motivated by profit and not altruism, the rapturous reaction of the public – who treated the women like rock stars for the duration of their stay from mid-August to early September – was entirely organic and is palpable in the film.

By contrast, when the women returned home to Europe and Argentina after COPA 71, they received virtually no press coverage. It was as if the event had never happened. Skepticism and stigma around women’s sport stymied what should have been a celebration.

“I was also surprised by the extent to which many of the players themselves went to hide their achievements, even from their families,” says Erskine. “These women had done this remarkable thing of representing their country on the biggest stage of all time yet were pressured to feel that they didn’t really do it. They were gaslit, and many didn’t speak about it ever.”

With their exhaustively researched, often laugh-out-loud funny, and very timely film – arriving as women’s sports records continue to be set – Ramsay and Erskine hope to finally right that historical wrong. It’s a goal that’s not without its challenges.

“The most difficult footage to find was of the tournament itself,” Erskine says. “Towards the end, we hit upon a collector in Mexico City whose grandfather had filmed the event in 1971 which turned up a bunch of footage from inside the stadium that no one had seen before. We were delighted!”

Still photos also help tell the story. As Ramsay explains, an archive belonging to the daily newspaper El Heraldo yielded the filmmakers some 2,000 photographs, mostly black and white, which were subsequently coloured and used extensively in the film.

As for those former players, who remain sharp as tacks, Ramsay says they are “taking back their own story.

“At the end of all the interviews, when we asked the women what they would like to say to their younger selves if they could, all of them — regardless of their background or language or which team they were playing on — said, ‘Don’t let anyone tell you what to do. Be yourself, and keep going,’” Ramsay says.

“That sense of sisterhood felt very special.”

RELATED: