‘Priscilla’ Finally Gives the Keeper of Elvis’ Legacy Her Due, While Scrubbing Away Some of the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll’s Shine

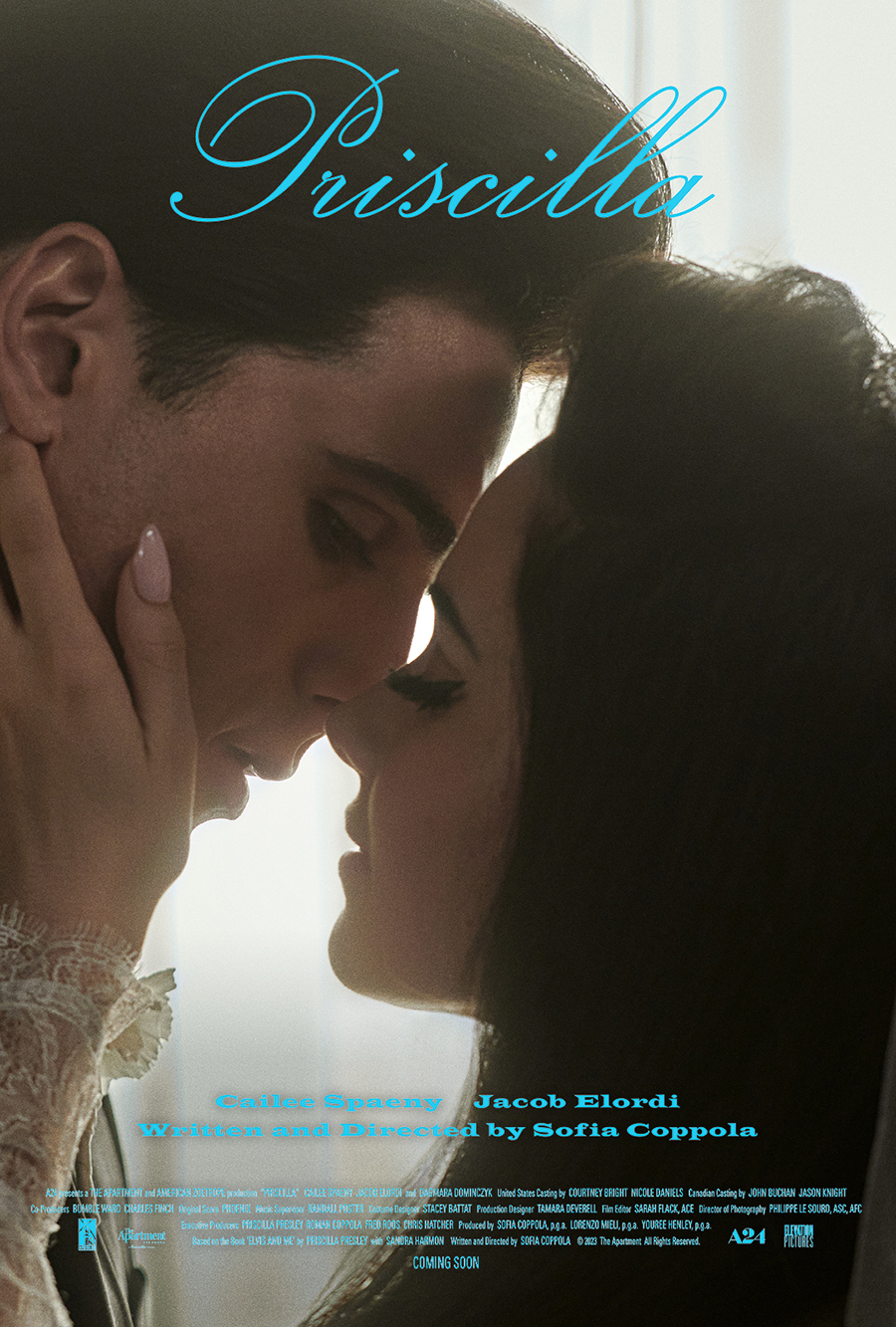

Jacob Elordi as Elvis and Cailee Spaeny as Priscilla Presley, in Sofia Coppola's 'Priscilla.' The film is already being hailed as one of the best films of the year. Photo: Elevation Pictures

In Priscilla, Sofia Coppola’s achingly melancholic look at the young woman whose life has been tethered to Elvis Presley’s, there’s a moment when the King of Rock ’n’ Roll whispers affections into his would-be bride’s ear. “Promise me you’ll stay the way you are,” he tells her. It’s a foreboding compliment, suggesting she stay frozen in time like so many ornaments that decorate Elvis’ Graceland mansion. Coppola’s film, starring Cailee Spaeny as Priscilla Presley, is about how the young woman slowly reckons with those words and rebels by growing, evolving and asserting herself from underneath his shadow.

Priscilla, meanwhile, couldn’t be more different from last year’s Elvis. The Oscar-nominated movie from Baz Luhrmann dripped with the same bedazzled showmanship that its namesake was famous for, while keeping Priscilla entirely on the margins, if not offscreen altogether. As caretaker to Elvis’s legacy, Priscilla gave Luhrmann’s sensational aggrandizement her stamp of approval.

But she’s also an executive producer on Coppola’s Priscilla, which is such a brutally honest and often unflattering take on their marriage, and Elvis, that it pricks like a thorn at the side of Luhrmann’s spectacular myth–making.

Luhrmann’s Elvis, starring Austin Butler, framed the Hound Dog singer’s rise, fame and ultimate demise in such a way as to project most of the singer’s faults onto his manager Colonel Tom Parker, played as a manipulative, bottom-feeding tyrant by Tom Hanks. The most glaring instance is how the movie alleviates any white guilt over Elvis’s cultural appropriation of Black musical styles. Luhrmann’s film paints Elvis as a bleeding heart for the Civil Rights movement, even though the singer did absolutely nothing on record to advocate for the Black community. The film goes on to pin Elvis’s silence on such matters on Parker, suggesting the manager forbid the star from getting involved in politics. There’s an entire section depicting Elvis’s sad face over Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination, a hollow unearned projection seemingly made to protect Elvis’s reputation.

While not at all its intent, Priscilla is like the nail polish remover scrubbing away at that shine. The stark contrast between the two films is obvious from who they cast as Elvis. Instead of Butler’s soft, doe-eyed, innocent-looking face, Priscilla gives us actor Jacob Elordi, whose more cutting, protracted and angular features were so well used in the popular series Euphoria, where he brought menace, desperation and even some empathy to his role as a toxic and violent high school bully. Coppola totally knew what she was doing casting him as the man who sings Love Me Tender.

By the way, you won’t hear Love Me Tender in Priscilla. Elvis’s estate didn’t approve his music to be used in Coppola’s adaption of Priscilla’s 1985 memoir, Elvis and Me, where the rock legend’s ex-wife looks back at the “fairy-tale” romance and fills in details of extra-marital affairs and neglect.

The film opens with a telling montage of Priscilla getting made-up opposite the porcelain figures around Graceland. From there, we go back to the moment when she’s practically scouted by Elvis’s military friend and chaperoned to his parties at the shockingly vulnerable age of 14. We see her ushered into the backs of cars and passed between patriarchal figures, from stepfather to Elvis.

While Priscilla would describe her relationship with Elvis at this young age as entirely wholesome, insisting in interviews that sex was not a factor, Coppola doesn’t let the predatory nature of the relationship slide. Party scenes where Elvis secretly instructs the underaged Priscilla to retire to the bedroom ahead of him are sufficiently off-putting, even as Elordi and Spaeney’s wonderful performances do suggest an emotional connection.

The tension between genuine affection and abusive and domineering behaviour continues throughout the film, over scenes where Elvis dictates Priscilla’s wardrobe, lifestyle and whether or not she has a say in just about anything. Even his marriage proposal isn’t a question so much as a command. Coppola takes great interest in the way Priscilla asserts herself, by wearing prints that Elvis can’t stand or changing her hair to express how she’s moved on.

The filmmaker is operating well within her wheelhouse, so much so that it’s easy to dismiss the specific artistry she’s bringing to the table here. Throughout her career, Coppola’s given us coming-of-age stories about young women feeling suffocated by patriarchal expectations (The Virgin Suicides, Marie Antoinette) or struggling to find themselves while living in a man’s shadow (Lost In Translation, On The Rocks and her masterpiece, Somewhere).

In Priscilla, Coppola is working with a subject who seems willing to sacrifice her own identity at Elvis’s altar. The source material, after all, is titled Elvis and Me, as if Priscilla, still holding on to Elvis’s surname, has resigned herself to being forever attached to that legacy. Coppola, by titling her own movie Priscilla, defiantly fights to make the character stand apart, even if she’s compelled to do so quietly.

She also anchors Priscilla’s extraordinary story with those moments and emotions that feel universal — from first love flutters to the loneliness of a crowded room. This story could just as easily speak to a young girl in the era of TikTok, who sees in Priscilla one of the very first influencers performing what others expect her to be.

Priscilla’s story doesn’t feel frozen in time. That’s Coppola’s gift to her.

Priscilla opens in theatres Nov. 3.

RELATED: