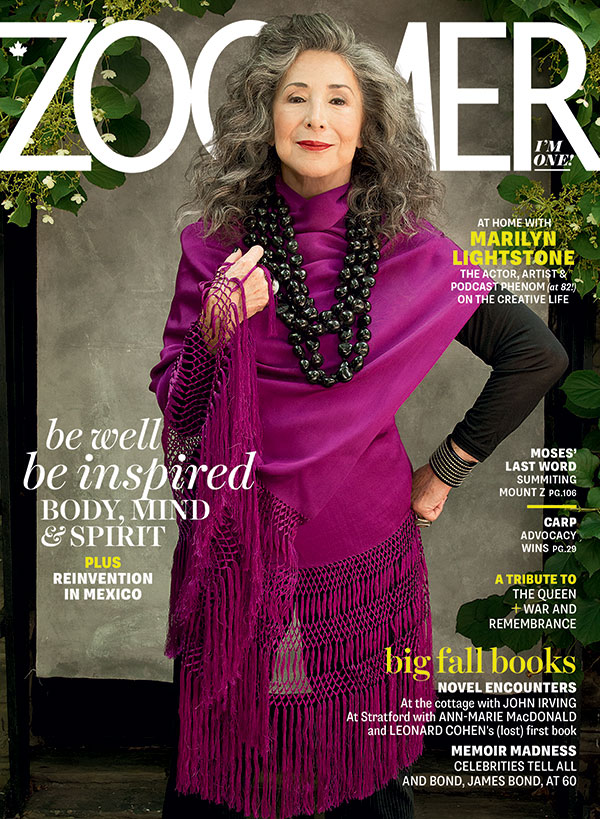

A Force of Nature: Marilyn Lightstone On Her Most Iconic Roles and Multifaceted Second Act

ON GOLDEN POND: Lightstone with her garden’s koi. Style note: Fall’s key looks layer on textures, tones and metallics for day-to-night drama. Beauty note: Replenish and recharge the skin. Try: Clarins reformulated Super Restorative Day Cream. Photo: Paul Alexander

Marilyn Lightstone is leading the way to her sanctuaries, plural. There are six outdoor “rooms” in her breathtaking, multi-level garden, an oasis spread across a hidden acre in the west end of Toronto. It is close to civilization, yet remarkably silent, save for a soothing natural soundtrack: rustling leaves, water trickling down a rock face into the koi pond, the periodic chirrup of birds. It is cool and breezy under the sun-dappled canopy of trees, despite the relentless summer humidity.

Lightstone is the ultimate multi-hyphenate: actress of stage, screen and television; painter; writer; podcaster; singer; and TV and radio host. She floats down the hill in her gauzy white summer tunic and trousers, her Indian-style thongs lightly tapping out a rhythm on the meandering rock path. Sure of foot and strong of voice, with a glowing complexion and almost unnerving poise, she defies her 82 years.

The lush gardens are anchored by the sprawling but cosy Arts and Crafts-style house she has shared with her partner, media mogul Moses Znaimer, the founder and CEO of Zoomer Media, since they bought the place in 1974. The transformation of the grounds is ongoing and evolving, and mimics her prolific career arc.

Lightstone plucks a sarsaparilla leaf and waves it in the air, admiring its wondrous complexity. “Nature is an endless inspiration,” she says, and indeed, the fruits of her gardens are often the subjects of her paintings. The gardens are a reflection of the artist who has reinvented herself through so many branches of the arts.

Her voice is rich, round and burnished, and when she leans in, it is as if you are being taken into a confidence. “I get called for parts these days, playing the Jewish grandmother,” she says. “That doesn’t interest me.” Now that acting is on the back burner, she has a wellspring of new projects to feed her soul. “Nobody is interested in an aging actress, especially a character actress. The kind of actresses agents and casting directors interest themselves in are young things. So I made up my own things to do.”

Many listeners wind down to Lightstone’s voice every night at 11 p.m. ET with Nocturne, her radio show on The New Classical FM, where she opens with a monologue, plays themed classical selections interspersed with poetry readings and recitations of writings about the musicians she’s selected. I confess I listened to her every night after I left the hospital when my mother was ill. Lightstone’s voice lowered my pounding heart rate and kept me company on those long, lonely, late drives home, my stomach churning with sour coffee.

“Oh, I thought you were going to say Your All Time Classic Hit Parade!” she interjects when I tell her I’m a fan of her work, name-checking her Friday-night VisionTV musical ensemble show, filmed before a live studio audience that sings along. Built around the Great American Songbook — the big band and show tunes of the early- to mid-20th century — it has been an unexpected hit, and is about to start filming its fourth season.

“We get a lot of letters thanking us, from families who connect with their parents over the show, and who come together around the TV on a Friday night,” she says.

But it is a newer venture still, her pandemic-era podcast Marilyn Lightstone Reads — launched in September 2020 and available on this magazine’s book club website — that is having a moment. There have been some 400,000 downloads of her renditions of classic novels such as The Age of Innocence, Jane Eyre, Pride and Prejudice, The Woman in White, Show Boat and, of course, Anne of Green Gables, where you can hear Lightstone reprise the role of Miss Muriel Stacey, for which she is beloved by international audiences.

“I act out every part,” she says. “I’ve always loved reading aloud, to whoever was willing to listen.”

This is where you really experience the range of her voice and her skill as she transforms from one character to the next, and then deftly back to the narrator. Her nuanced tone is so beguiling, she is also the voice of numerous Zoomer Media radio and TV properties — The New Classical FM, VisionTV and ONETV — recording station intros and taglines, promos and coming-soons.

It was her acting career that took centre stage this summer, when the 30th annual Toronto Jewish Film Festival (TJFF) honoured Lightstone with a tribute, and programmed a slate of her classic films.

“It was a wonderful day to share with people from different moments of my career, and my life,” she says, settling in with an iced coffee to one of the many discreet seating areas dotting the garden.

Lightstone is probably best known as the maternal and inspirational teacher Miss Stacey in the popular TV series Anne of Green Gables and Road to Avonlea, which aired on CBC. But in the ’70s and ’80s, she also starred in a run of critically acclaimed films, from 1975’s Lies My Father Told Me (for which she won a Genie Award for Best Actress) to In Praise of Older Women (1978) and The Tin Flute (1983), based on the novel by Gabrielle Roy, which earned her an Award of Merit at the Moscow Film Festival. This was a fertile and febrile moment in nascent Canadian cinema and Lightstone was in the middle of it. Older Women, in particular, in which Lightstone played a divorcee who seduces a younger man (played by Tom Berenger) was the subject of roiling controversy over nudity and sex scenes, and the cuts required by the Ontario Censor Board, before it could be premiered at the 1978 Festival of Festivals (which later became the Toronto International Film Festival).

One of the films shown in the TJFF series was The Wild Pony, a seldom-seen 1983 Pay-TV movie directed by Kevin Sullivan, with whom Lightstone would go on to make the Green Gables series.

“I immediately fell under Marilyn’s spell as she expressed her ideas and determination to play this very independent character,” says Sullivan, describing a desperate mother trying to keep her tiny family together by convincing the man responsible for her husband’s accidental death to marry her.

“Marilyn had such warmth and transparent honesty as we discussed the complexity of this character, that I kind of knew immediately she could bring the woman to life with enormous aplomb.”

The stage was her first love, though. As Stuart Hands, programme director of the TJFF, says, “It is a shame so little of her theatre work has been preserved.” To Lightstone, however, the ephemeral nature of the work is part of its magic in her memories. Highlights include the role of Goneril in King Lear at the Lincoln Center in New York (opposite Lee J. Cobb) in 1968; Masha in Chekhov’s The Seagull with William Hutt at the Stratford Festival, also in 1968; and Leah in The Dybbuk, winner of a Los Angeles Drama Critics Award for Best Production in 1975. As she says to the crowd at the TJFF tribute: “There I was, lying on the floor, possessed, surrounded in the synagogue by rabbis in ram’s heads,” noting that was the moment she realized what a cool thing she got to do for a living. “Most of the things women get to play are so limited in scope. This was like somebody has handed you a great big present; you just unwrap the ribbons and wrapping paper with great relish.”

Lightstone spent a big chunk of her theatre life as an original cast member in the New York and Los Angeles productions of Tamara, the three-dimensional, audience-interactive play, produced by Znaimer, which debuted in Toronto in 1981 and ran for more than 10 years around the world. The plot featured the Polish painter, Tamara de Lempicka, in the elaborate home of Italian war hero, poet and lover Gabriele D’Annunzio, where he was under house arrest. Much drama ensued. It also travelled to Buenos Aires, Portugal, Warsaw, Mexico City and Rome, and starred, at various points, Anjelica Huston, Helen Shaver, and co-starred Cynthia Dale.

“It took place over four floors; we would run 26 sets of stairs, in heels,” Lightstone remembers, adding there were 10 characters and 100 scenes, with the audience moving between “sets” so no one ever saw the same play. As part of the show, she cooked an omelette with French chef Daniel Boulud, who was relatively unknown then, but would go on to become a Michelin-starred celebrity. Audience members often stayed around after the scene and ate it, much to her amusement.

The Tamara years led Lightstone to extended stints in the entertainment capitals of Los Angeles and New York, working on commercials and voice roles in animated films, and she’s glad she took her dreams to Hollywood and the Big Apple. “I had to get it out of my system.”

She pauses to express gratitude to her life partner of six decades, a sentiment she repeats several times over the course of our conversations. “None of this would have happened without Moses,” she says. “Even as someone younger, as an actress, you have to have someone who is on your team. You have to have a champion.”

The other source of ballast for Lightstone’s creative life came early on. Her parents were unusually supportive of their daughter doing her own thing, as in becoming an actress, a field not known for inspiring joy in the hearts of parents, especially in the early 1960s.

She takes us back to her working-class childhood in what was then the Jewish ghetto in Montreal. Her world view was formed on Clark Street, just a few blocks from where Lies My Father Told Me was filmed. Her father was a printer by trade; her mother, a housewife. They lived, with her two younger brothers, in a small flat, along with her maternal grandmother, “with no privacy.”

High school was Baron Byng. “It was a school that was really built in order to house immigrant kids, and Jewish kids in particular.” Lightstone stood out. “In contrast to many of the other kids in my high school, who were either immigrants themselves or their parents were, my parents were Canadian-born and my grandparents came to North America when they were very small children. So a lot of the parents of the kids I knew in high school, they thought I was a gentile girl because I didn’t sound like them.”

Many of her classmates’ parents had been through horrendous ordeals — some had been in Nazi concentration camps — and had lost, or been separated from, family members. “[Their kids] were under pressure to live safe, conventional lives, because their parents just wanted them to be safe and conventional and happy, and didn’t want them to take any risks of any kind.”

Perhaps, she muses, without that heavy legacy, the Lightstones were freer to encourage their daughter to be the artist her soul demanded, which was remarkably progressive for the era. It is easy to forget how rigid things used to be, when the professions open to women of her era were teaching, nursing, physiotherapy and library science.

“I never wanted to walk the path. I was just allowed to follow my heart, with tremendous support,” says Lightstone. “Nobody told me what I could and couldn’t do. Or if they tried, they didn’t get very far.”

Lightstone met Znaimer in 1960 when they were both students at McGill University and acted together in a Player’s Club production, even though they tell slightly different versions of the beginning of their romance. “Moses always likes to make a story better,” says Lightstone, “but we won’t contradict him.”

Znaimer cottoned on to the attractions of the thespian lifestyle early. “All the independent women were in show business,” he says, recalling the pivotal moment he connected with Lightstone at a cast party. “She was a star on campus. She was very mature, and an older woman, two years ahead in school. She affected a rather serene and much more professional demeanour compared to all the others.” He walked her home. “It was rather a long walk, as she lived on the other side of town. It’s been 62 years. I’m thinking of asking her to go steady,” he jokes. For her part, Lightstone recalls how he caught her eye, with his feet up confidently on a chair in the rehearsal room. She waited for him to indicate interest; if he showed up at the cast party, she says, it was meant to be. She doesn’t recall the long walk home, but deeply enjoys Znaimer’s embellishment here.

After Lightstone graduated, she had a successful audition with the National Theatre School (NTS), which had just opened the year before “in the old Canadian Legion Hall” on rue de la Montagne. “The timing was very lucky,” she says, adding that, before that, you would have to go to London or to New York to make your career. She couldn’t do that; there just wasn’t the money. “I just loved it. It was just where I should be,” she says. “What else I would have done, I have no idea.”

She went into the NTS “completely green, and maybe that is a good thing,” since students who had taken acting lessons were promptly told to unlearn them. There were some extraordinary people, including a teacher who had taught Christopher Plummer and that legend of the Stratford boards, William Hutt. Lightstone credits the school with instilling discipline — “to this day, I can’t tolerate sloppy” — and the ability to work in an ensemble. “You only get your best performance if someone else is really good, too. It is like exchanging energy back and forth.”

The hows and whys of acting inspired Lightstone to write her 2001 novel, Rogues and Vagabonds.

“I wanted to explain what it was like to be an actor. How we do what we do, the process and the craft.” In it, the theatre brings together an unlikely group of characters — a Lothario, a gay variety-show performer, a temptress and a rule-breaking mentor — in an intricate story with loads of deftly written sex scenes, abundant interpersonal dramas and precipitous plot twists. In this world, passions run high, but artists stumble over the more mundane stuff of life. The cover of the novel features a painting of her by artist Heather Cooper that hangs in Lightstone’s kitchen. The book isn’t autobiographical, and there is no discernible “Marilyn” character, but the choice of cover links it to her artistic mythology.

When asked why she is compelled to create in so many mediums, she answers: “Because I have to. It has to come out somewhere, somehow.” Znaimer says living with Lightstone reveals her “relentless drive” to create. “She doesn’t have to work. She doesn’t have to work that hard. That is what is admirable.”

Lightstone leads me inside the house to explore. There are several paintings of the couple, together and separately, but one stands out. Just inside the front door, lit up at the top of a stairway, is a unique double painting of Lightstone and Znaimer, by Canadian art legend Charles Pachter, who is also a long-time

friend of the pair (they met in the early ’70s). “The painting of Moses is at a table, looking straight at the viewer,” says Pachter. The second canvas is positioned on the adjoining corner wall. “She is looking straight at him. I painted them on two canvases, in case they break up,” he jokes.

“I painted it years ago. She called me the other day, out of the blue, to tell me how much she loves it,” Pachter says. “That means a lot, to hear someone continues to appreciate your work.” Lightstone has known Pachter so long, she was one of his “handmaidens” at his 2018 wedding to Keith Lem, alongside Margaret Atwood, who was the “head handmaiden,” a.k.a. maid of honour.

“She is a terrific writer, artist, gardener, epicurean,” Pachter says of Lightstone. “But mostly she is affable, kind and elegant.”

She talks about the life of a working actor away from home, how a community builds up around a production or film or TV set, then everyone disperses. “It can be lonely at times,” Lightstone concedes.

For a while after Lightstone stopped travelling back and forth from L.A., she had an art studio in an industrial area of town. She has since taken up photography, plays around with digital compositions on her iPad and has an enthusiastic presence on Instagram, but she still paints regularly. “I’m increasingly attracted to doing abstract. I somehow always kind of scoffed at abstract art, I never sort of believed in it,” she says. “One night, I went to my studio, turned on the radio to JazzFM. Jazz had never been my favourite. But I got a canvas ready and started. Suddenly, I looked down; I [realized that I had] just painted an abstract painting. And I liked it. There is an intellectual aspect to it that I never twigged to before. I discovered my quintessential style in doing abstract work.”

The abstracts stuck, the jazz not so much. The Great American Songbook remains the soundtrack of Lightstone’s life. “These are the songs that move me,” she says. It was a desire to work with her long-time collaborator, David Warrack — a composer, conductor, pianist, musical director and vocalist — to explore the popular songs of the early 20th century that drove Lightstone to create Hit Parade.

Warrack, who is the musical director on the program, met Lightstone 50 years ago when she was playing the lead in Mary, Queen of Scots at the Charlottetown Festival and he was the musical adviser. They’ve collaborated ever since, and he arranged Lightstone’s 2018 poetic take of “In Flanders Fields,” which she recorded with the Canadian Men’s Chorus, accompanied by Warrack on the piano, and “The Light Shines All Over the World,” her non-denominational holiday carol. “She’s got class,” Warrack says. “Sometimes she can be as annoying as hell, because she demands the best.”

He says Lightstone suspected Hit Parade would strike a chord in people, and she was right. “Maybe it is something as simple as the fact that in a very complicated world, there is an appeal to something so accessible and nostalgic.”

As she leads me out of the house, we pause to admire the tiny, gilt-framed newspaper advertisement that drew her to the place. It is part of the house’s mythology now, its origin story. Back in the garden, the same muffled hush falls over us like a spell. The lush, multi-levelled greenery is an apt metaphor for Lightstone and the creative tendrils that shoot out in so many directions. She seems to have boundless faith that the buds of new ideas and projects will continue to bloom. Her confidence floors me, as it is rare to have that kind of faith in oneself, and it certainly is foreign to me.

Being different doesn’t faze her. “All my life I wanted to be an artist of some kind. I thought I was going to be a painter, and I continue to be,” she says. “Artists are different from other people.”

All wardrobe for this portfolio, Lightstone’s own. Prop Stylist, Daniel Onori/P1M.ca; Hair, Janet Jackson for L’Oréal Paris/P1M.ca; Makeup, Tana D’Amico for @maccosmetics.ca

A version this article appeared in the Oct/Nov 2022 issue with the headline ‘A Force of Nature, p. 36.

RELATED: