Sharon Robinson Shares Memories of Leonard Cohen Ahead of New AGO Exhibit, ‘Everybody Knows’

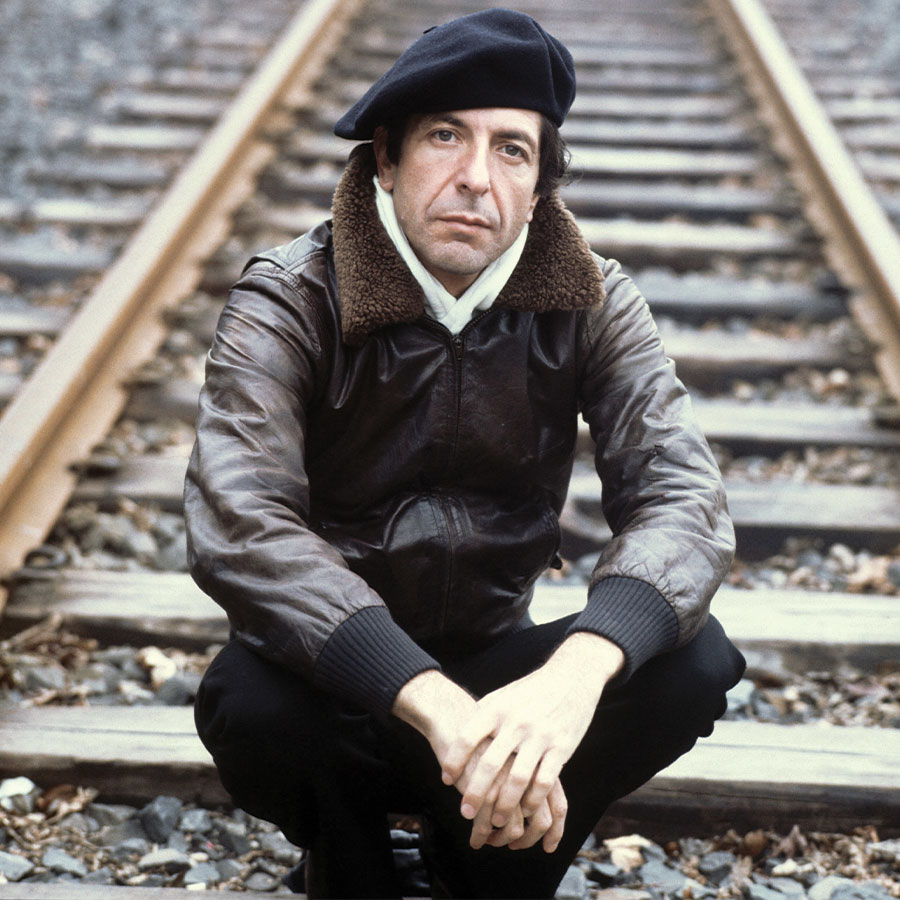

Leonard Cohen in Frankfurt, Germany, April 25, 1976. Photo: Istvan Bajzat/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

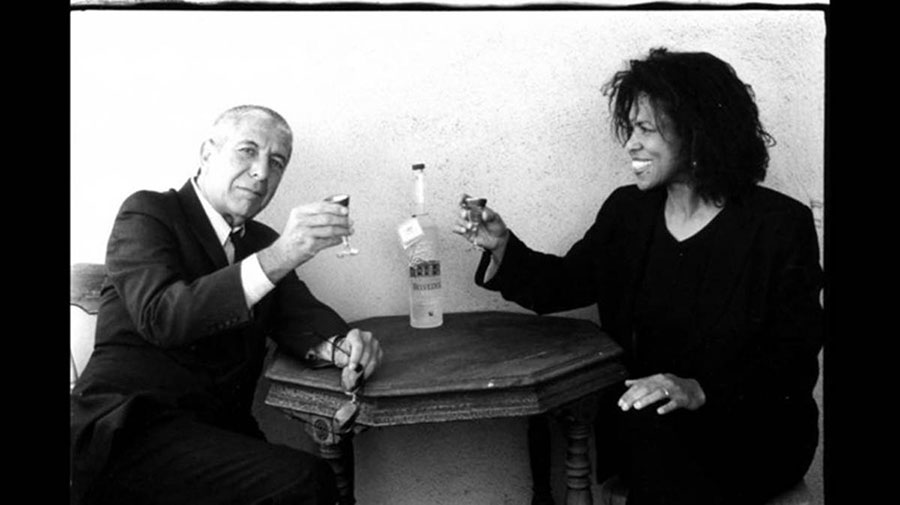

Singer, keyboardist, songwriter and record producer Sharon Robinson may have won a Grammy for writing “New Attitude” — the hit sung by Patti LaBelle on the Beverly Hills Cop soundtrack — in 1985. But it’s the legacy of her longtime collaboration and friendship with Montreal-born troubadour Leonard Cohen, who died in 2016 at the age of 82, that still resonates.

Robinson, 64, proved one of Cohen’s favoured artistic collaborators, and their musical careers were entwined for nearly four decades. Initially, the San Francisco-born Robinson was a backup singer on the 1979 “Field Commander Cohen” tour before expanding to the role of creative collaborator and setting the legendary poet, novelist and songwriter’s lyrics about beauty, decay, loss and the human heart to music, as well as producing and arranging the songs. They share writing credit on tunes like “Everybody Knows,” “My Secret Life,” “Waiting for the Miracle,” “Alexandra Leaving” and “Boogie Street.”

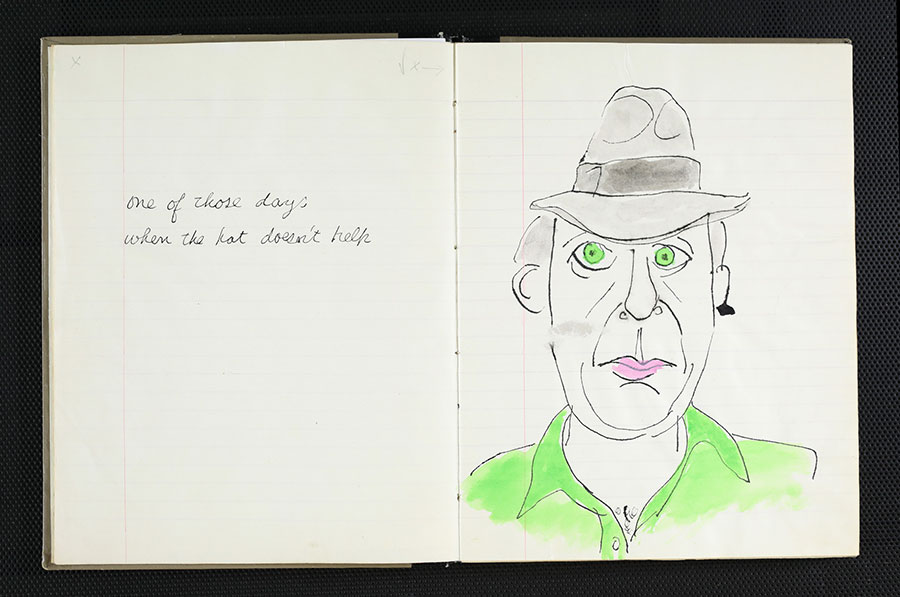

To inaugurate the Art Gallery of Ontario’s upcoming Everybody Knows, an immersive new exhibition that excavates the material of Cohen’s creative life — through everything from photographs and illustrations to Cohen’s notebooks and instruments — Robinson brings an intimate performance of her new show, My Time with Leonard Cohen, an evening of music and personal reminiscences, to the AGO on Dec. 9.

“He was very interested in the continued life of his writing and of his music,” Robinson said during a recent conversation with Zoomer about her life and work with Cohen.

Robinson continued, speaking about her memories of Cohen, the new AGO exhibit and her performance at the gallery.

NATHALIE ATKINSON: Several years ago your book of photographs, On Tour with Leonard Cohen, shared unguarded moments of reflection and contemplation with him. What else do you hope fans discover and appreciate about him through your performance at the AGO?

SHARON ROBINSON: I think that’s a nice characterization! My show is pretty much exactly that — I’m just reflecting on time I spent with Leonard, his graciousness, his generosity, sharing the very special moments spent writing songs with him. It’s kind of a recollection of those times with him. It was a way for me to incorporate the music as well as the stories, to just have people experience those moments. I think one of the things I’m sharing most is what it was like to be with Leonard and his personality — his humour and his graciousness. People have told me, ‘It feels like we were with him for that period of your show.’ I appreciate that.

NA: You’ve already taken the My Time with Leonard Cohen tour to several U.S. cities. Is it at all daunting bringing it to Cohen’s home country, where Canadians have such an immense sense of pride and proprietary feeling for him?

SR: It is different performing in Canada, for sure. But not in a bad way! I am actually really looking forward to doing this show for the Canadian audience, for people who know Leonard more than typical Americans do. I think some of my stories will resonate with them maybe a bit more. And I’m just really looking forward to seeing the AGO exhibit itself.

NA: I was going to ask if there was anything among his personal ephemera you were hoping to see again at the exhibit. I’m told the exhibition includes handwritten lyrics, books from his home library, photos, even musical instruments …

SR: I don’t know what’s in it, I don’t even know very much about it generally, so I’m really looking forward to seeing it. But I was sort of privy to Leonard’s personal life, so there probably wouldn’t be very much that would surprise me. [Laughs.]

NA: Lately it feels like I’m covering new Cohen material every few months — biographies, books like Who By Fire (about his tour of the Sinai desert during the Yom Kippur War), documentaries like Hallelujah (which you’re in), and the new collection of his unpublished early works, A Ballet of Lepers. Do you keep up on all the new material from the scholars and biographers and fans?

SR: You know, I am interested in some of the scholarly analyses but I don’t delve too deeply into the fan stuff — or even the biographies. I kind of like to preserve my memory of my friend and if I read a lot of other people’s take on Leonard, honestly, most of them didn’t know him as well as I did. So I like to preserve that special space for myself. It may sound a little snarky of me to say that, but …

NA: That’s fair — our collective cultural memory could impinge on yours.

SR: And he would always tell me not to read those books. He’d say, ‘Oh don’t read that darling.’ [Laughs.]

NA: In between all the tours and collaborations, you and Cohen remained in touch as close family friends. Cohen was godfather to your son Michael [Gold], who’s an accomplished musician himself. Given what Cohen called his ‘Franciscan tendencies,’ I can imagine he took that responsibility for spiritual formation seriously?

SR: My husband [the late commercial director Greg Gold] and my son were both very happy to have Leonard as a friend as well. We considered our families to be connected in that way and it was very special and very heartwarming. He did take his role as Michael’s godfather seriously. And he gave him a gift for his birthday every year. One of the gifts he gave him, on his 16th birthday, was a book on mixing drinks. [Laughs.]

NA: I read that your mother would often bake and send a cake over with you when you’d go to songwriting sessions at his kitchen table.

SR: She did! My mother’s fruitcakes were notorious and he absolutely loved them. He signed Dance Me to the End of Love to my mother and came over and visited her for a [big] birthday. Ironically, I just found the recipe a few days ago. It takes at least a week to make and I don’t know if I have that kind of time. [Chuckles.]

NA: Your Toronto show is long sold out so, for those readers who aren’t able to attend, please tell us a bit about the working relationship and creative shorthand you and Cohen shared.

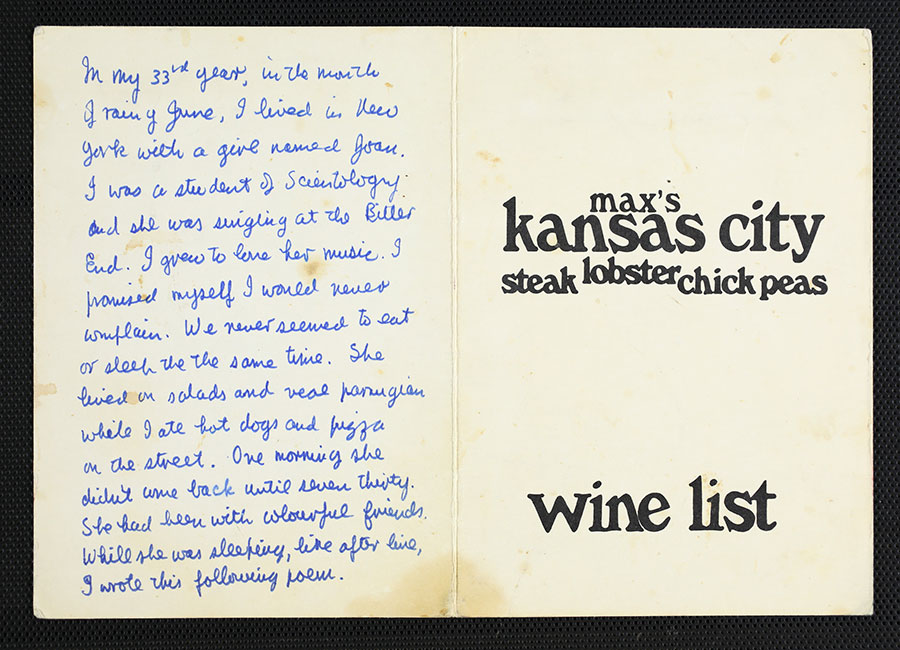

SR: He’d either invite me over or sent me an email with a lyric, he’d read through it, and then I would take the lyrics home and go to my piano. Because a poem is different from a song lyric, I would try to find what part is the verse or the chorus. Or maybe it’s just a series of verses (like some of the songs were). I’d take the words home with me and use them to construct a song and try to find a melody that reflected the intent of the lyric — but without overwhelming it, so that you could still focus on the words.

Obviously I saw the genius in his work, in his poetry. To be presented with one of his lyrics was an honour, really. That had a lot to do with it. Also, he was very warm and very friendly to me. We struck up an early rapport, which gave me the sense that I could step out of my lane as backup singer and ask him if he wanted to hear a melody. That was how it started. Later, he would contact me periodically with a lyric or an invitation to come over and work on something. So he was the one that really kept the collaboration alive.

NA: Has observing and being a part of his process up close over so many years influenced your own approach to your work?

SR: Yes, it definitely has. I mean, Leonard had a very clear vision of himself as an artist, which has been something at times elusive for me personally. So I think I learned a lot about that: The idea of not settling for anything that isn’t really working for you. As is well-known, Leonard would sometimes take years to write something — that’s because he never settled on something he wasn’t completely happy with. That pure artist mentality, which can get you in trouble in other aspects of your life! But Leonard was a true artist and there’s that lot to be learned from that.

NA: You started touring with Cohen you were in your 20s. Are there particular songs of his that resonate differently now at this age and stage of your life?

SR: Rather than a particular song, I would say that most of Leonard’s songs continue to reveal themselves over the years. And I know that’s more of a measure of your own development than it is anything that’s changing about the song. In 1979, I was just a young backup singer trying to do a job. [Laughs.]

NA: Bob Dylan’s new book looks at the idea of interpretation and how singers remake songs through their performances. Over the years there have been many interpretations of Cohen’s work — even just “Everybody Knows” has several notable covers. Do you have a favourite interpretation, by other artists, of one of the songs you created together?

SR: Let’s see. Not to the exclusion of everyone else of course, but I really love Don Henley’s “Everybody Knows” [from the ’90s]. I don’t know if it’s widely been heard.

NA: And now that you are performing the songs solo, are you playing with them in a different way than when you toured together or even the way you arranged them on your own debut album, Everybody Knows?

SR: Interesting that you would ask that because the first song we wrote for Ten New Songs was “In My Secret Life” and the other day I was experimenting with a really pared-down kind of arrangement, just turning the song really from a mid-tempo pop song to more of a ballad. And I’m really loving doing it that way because it causes even me to listen more to the lyrics and to get deeper into the place that Leonard was coming from when he was writing that lyric. I’m really thrilled with the song even more so than I ever have been before.

NA: A portion Cohen’s archive is here in Toronto at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. I think that’s where some of the never-before-published early works gathered in the new posthumous collection A Ballet of Lepers came from. It’s something like a hundred boxes of material. There’s a real sense of him self-consciously curating an afterlife for his creative process.

SR: He didn’t shy away from death. He was able to think about his work in that sort of posthumous time [way], which a lot of people don’t really do.

The AGO exhibit Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knowsopens to the general public on Dec. 13. Click here for more information.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.