No Time to Die: Tracing James Bond’s History in Jamaica as 007 Makes His Return to the Island

Actor Daniel Craig, 53, wraps up his tenure as James Bond in the upcoming film 'No Time to Die.' Zoomer's Deputy Editor Kim Honey followed 007’s footprints across Jamaica, where the suave spy was born on Ian Fleming’s typewriter at GoldenEye almost 70 years ago. Photo: TCD/Prod.DB/Alamy Stock photo

Looking for a new way to explore Jamaica? Here, we revisit our story tracing the rich history of 007 on the island, where the suave spy’s story was born on Ian Fleming’s typewriter, and where Bond made his return in the franchise’s latest instalment.

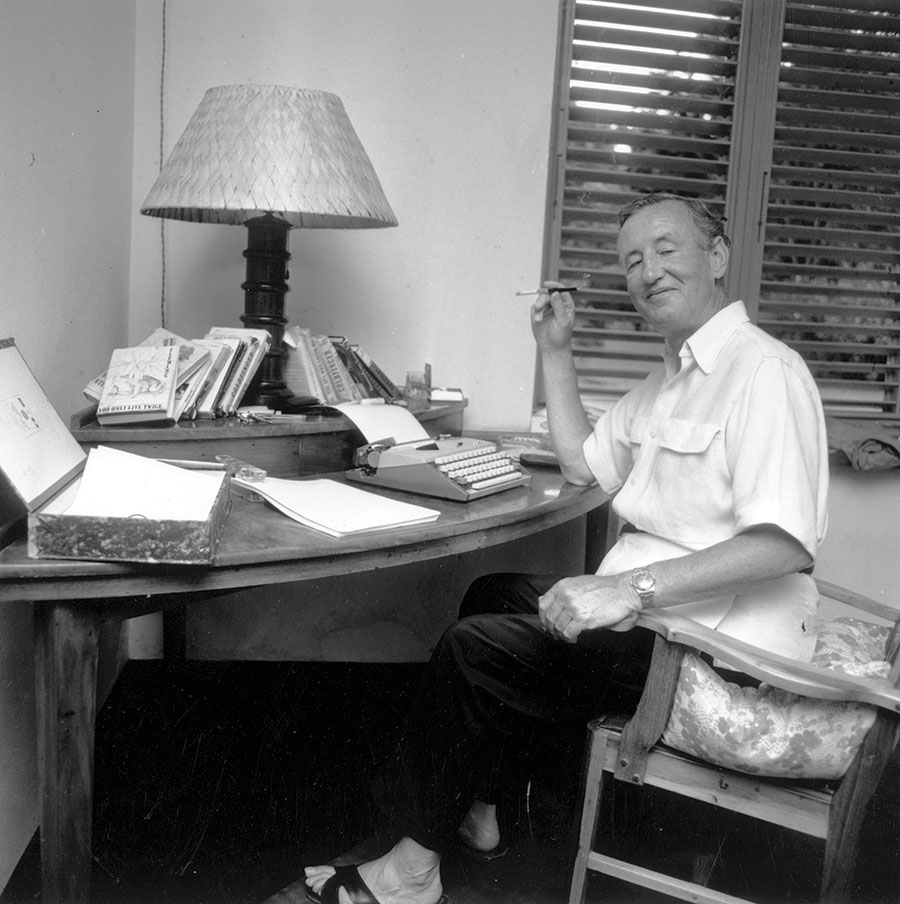

In Jamaica, you can’t throw a lemon peel from your Vesper martini without hitting a person, place or thing connected to James Bond. That’s quite a feat, considering the suave spy was conjured up almost 70 years ago by former British naval intelligence officer Ian Fleming on a typewriter at Goldeneye, his island getaway near Oracabessa on the north coast.

You can picture Fleming winging his way over Jamaica as he describes his fictional secret agent getting a glimpse of the lush colonial outpost from the air in Dr. No. “Bond watched the big green turtle-backed island grow on the horizon and the water below him turn from the dark blue of the Cuba Deep to the azure and milk of the inshore,” he wrote in 1957.

Just as “Bond’s heart lifted with the beauty of one of the most fertile islands in the world,” yours will, too, whether you are on the trail of 007 or what the author once called “the gorgeous vacuum of a Jamaican holiday.”

I’m on the Caribbean island in January, following in the footsteps of the secret service agent with an insatiable appetite for booze, women and cigarettes, eight months after shooting wrapped here on the latest instalment in the wildly successful global movie franchise. Since the first Bond movie, 1962’s Dr. No, was filmed not far from the house where Fleming enjoyed winter sojourns in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, the famed fictional spy has earned an estimated US $16.3 billion at the box office.

As Daniel Craig takes his fifth and final turn as 007 in No Time to Die, which is set to open in theatres Nov. 25, I’m exploring Bond’s Jamaican roots since Eon Productions Ltd. is billing the 25th movie as a repatriation of sorts. “We consider Jamaica [to be] Bond’s spiritual home, so he begins his journey here,” Eon’s co-owner and producer Barbara Broccoli, 59, explained in a behind-the-scenes interview at Goldeneye with the online movie platform CineMagna last year.

The world is a far different place than the day Fleming invented his spy with the wandering eye against the backdrop of the Cold War. The USSR has consciously uncoupled, 9/11 underlined new threats to world stability and the #MeToo era has made Bond’s trademark double entendres seem more than just louche, perhaps even bordering on sexual harassment. That’s why Broccoli took care to introduce strong female characters in No Time to Die, like a new 00 agent played by Lashana Lynch and a newbie CIA operative played by Ana de Armas. Then there is Léa Seydoux, who, as French psychologist Dr. Madeleine Swann, seems to tame her leading man in 2015’s Spectre and reprises her role in No Time to Die. Bond’s taste in women begins to evolve in Spectre, where the world’s sexiest spy has an assignation with Lucia Sciarra, played by Monica Bellucci. At 50, the Italian actress has turned the juvenile Bond girl trope on its head.

Craig has given the character “a depth and inner life” compared to Fleming’s literary version, which Broccoli has called a silhouette. “We were looking for a 21st-century hero, and that’s what he delivered,” she told Variety in 2019. “He bleeds; he cries; he’s very contemporary.”

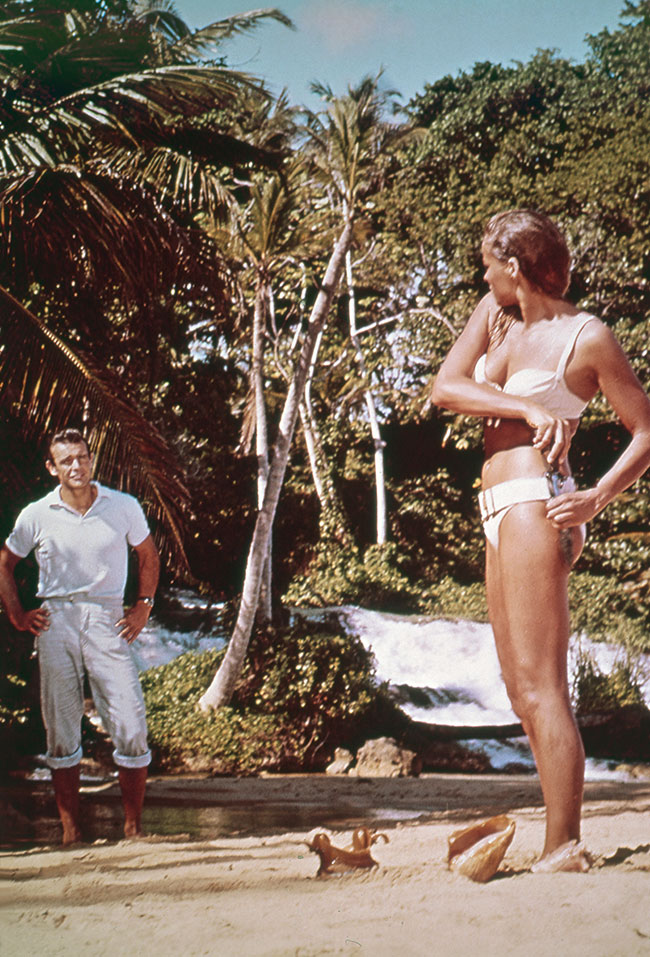

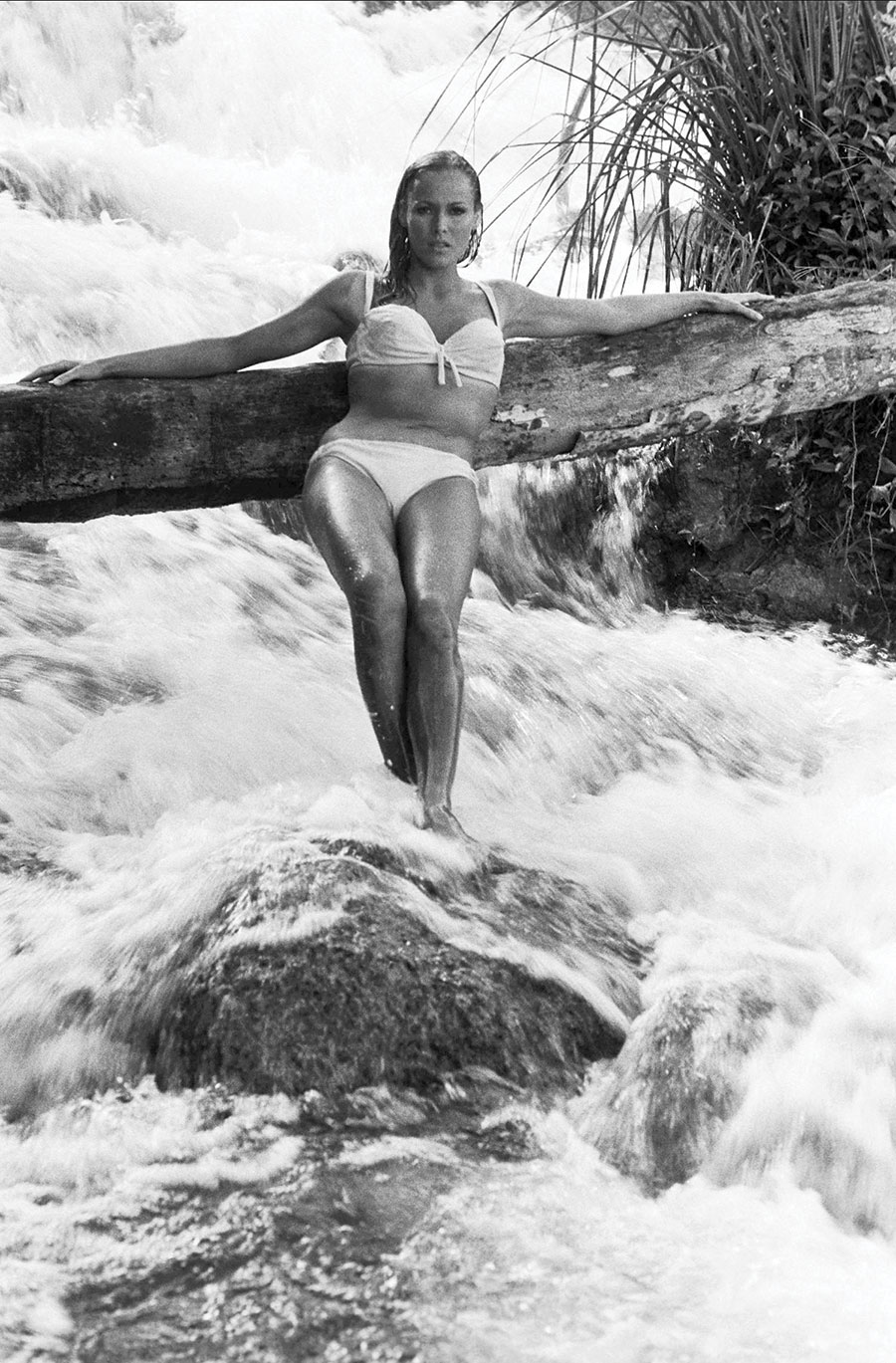

She was a babe in her mother’s arms when they watched her father, Albert (Cubby) Broccoli, film an iconic scene from Dr. No about 25 kilometres east of Goldeneye at Laughing Waters Beach. That famed stretch of pristine golden sand is as deserted as the day Sean Connery ogled a ravishing Ursula Andress as she emerged from the surf, singing “Underneath the Mango Tree” in a white bikini with a knife strapped to its belt and a conch shell in each hand. Whether you’ve seen Dr. No or not, that first glimpse of the original Bond girl, Honey Ryder, has been burned into the retinas of the world’s eyes.

Bond fans can visit the beach near Dunn’s River Falls in Ochos Rios to recreate the Andress scene and snap a photo where the river becomes a picturesque waterfall as it tumbles out to sea, although they have to call the St. Ann Development Company Ltd. to make an appointment.

In No Time to Die, Bond has retired to another crescent of sand, this one 115 kilometres east of Laughing Waters in Port Antonio. The movie’s trailer shows a bird’s-eye view of a sailboat plying azure waters, then cuts to Craig, his back to the camera, gazing out to sea from the wooden deck of a beach house. Built on a private stretch of San San Beach, the detailed set had local books on the coffee table and a Jamaican kitchen staple, a Dutch pot, on the stove. It’s so remote, Eon hired divers to bring construction supplies to the beach, according to Renée Robinson, Jamaica’s film commissioner.

The movie provided a substantial boost to the local economy, but a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) prevents Robinson from saying how much Eon spent in Jamaica. Film commission statistics show 104 productions, including Bond 25, spent US$18.6 million in 2018-2019, while 124 productions spent $8.9 million the year before. “You can do the math,” she joked.

It’s safe to say it is a fraction of the film budget, given that IMDb’s Box Office Mojo reported Spectre cost $324 million to make and brought in $1.2 billion at the box office.

No Time to Die’s plot was shrouded in secrecy by reams of NDAs signed by everyone who worked on the Jamaican locations from Robinson down to the drivers who ferried actors and crew to the sets. Before the film’s release, all that could be gleaned from the official trailer and previous interviews with Broccoli is this: Bond is enjoying retirement in Jamaica when he is convinced to help rescue a kidnapped scientist.

Not a trace of the beach house remains at San San. Other locations in Port Antonio are similarly absent any signs of movie-making. At the abandoned Boundbrook Wharf, which was transformed into a Cuban customs port with murals of Fidel Castro, the concrete floor is covered in goat droppings and bird guano, and bats roost in the rafters overhead.

My driver and guide, who both worked on the film, say a boat was blown up out on the bay; a scene with a plane took place at the secluded, one-strip Ken Jones Aerodrome 10 kilometres outside town; and on West Street near Musgrave Market, Craig was filmed driving a blue open-top Jeep near the jammed parking lot where a shoeless man now sleeps peacefully on a sliver of grass next to the cenotaph.

All that’s left are the stories and, on an island full of raconteurs, these are far more entertaining.

At Geejam Hotel near the community of Drapers, owner Steve Beaver has anecdotes galore involving Amy Winehouse, Alicia Keys and Gwen Stefani, all of whom laid down tracks at his tiny Geejam Recording Studio. In the last year alone, he hosted Beyoncé and Jay-Z, British singer Harry Styles and, of course, Daniel Craig. All stayed at the exclusive six-bedroom villa called Cocosan, which costs US$6,000 a night in high season and has a lap pool, an impressive collection of vinyl records, a red lacquered piano and balconies overlooking the Caribbean coastline. When No Time to Die was filming at nearby San San Beach, the hotel’s Bushbar was party central for the crew.

The further you get from the present, the more convoluted – and sometimes taller – the tales become. You can get quite lost following Bond across this jewel-toned island, which seduced Ian Fleming on his first visit in 1943 when he drank in its aquamarine water, emerald-green forests and topaz sunsets, along with a healthy amount of alcohol.

“When we have won this blasted war, I am going to live in Jamaica,” he told his college friend Ivar Bryce following an Anglo-American naval conference in Kingston. “Just live in Jamaica and lap it up and swim in the sea and write books.”

About that Vesper martini. Before Jamaica Inn manager Kyle Mais launches into its creation story, he prefaces it with smatterings of “it was rumoured” and “it was only ever passed down” before introducing his bartender, Teddy Tucker, who has worked at the Ochos Rios hotel since 1969. Mais says Tucker heard that Fleming and former British prime minister Winston Churchill – who wrote Fleming’s father’s obituary after he died in the First World War – were drinking at the inn when they decided to order martinis. “Someone came up with the idea of asking the bartender to put a lot of ice in the shaker and shake and shake and shake it and get it really cold,” Mais says from a perch on the stunning veranda. “It’s Jamaica. It’s hot and humid. You want a refreshing drink. Why not make sure it was shaken, not stirred? That’s where this whole concept originated.”

Meanwhile, British lore has it that Fleming inventing the shaken cocktail – named after Bond girl Vesper Lynd and mentioned in his first novel, 1953’s Casino Royale – at one of his regular haunts, Dukes Hotel bar in London.

The Bond story in Jamaica is complicated by criss-crossing story lines that begin with Fleming, an upper-class Eton-educated Brit who socialized with the boldface names who treated the island like their private playground after the war.

At the time, Goldeneye was a spartan home with steep stairs leading down to its tiny, private beach. In an interview published four months after he died of a heart attack in 1964, Fleming told Playboy magazinehe would swim nude every morning and prowl the reef with snorkel and spear in the afternoon, looking for lobster.

Fleming’s writing was as inspired by Jamaica and its colourful cast of characters as his work as a naval intelligence officer in the Second World War. He even stole the name James Bond from a well-known U.S. ornithologist who wrote a book on birds of the Caribbean. Local flora and fauna show up in his work, particularly the marine life he observed on snorkelling expeditions like octopus, squid, barracuda and crabs. In his hands, they were often turned into malevolent man-eaters.

On my 2020 visit to GoldenEye Resort, the beach looks much the same as it did when Fleming was photographed there barefoot, in black trousers and a white belted shirt, as an employee raked the sand behind him.

The property is now called Fleming Villa, part of the resort owned by Island Records founder Chris Blackwell, the man who introduced Bob Marley – and reggae – to the world. It now sleeps 10, rents for US$10,000 a night in high season and features overstuffed couches, an outdoor bathtub, in-ground pool, a massive media room and one-bedroom guest huts.

Two almond trees still frame a sweeping view of the coast from a dining table in the garden, and the corner desk made of local blue mahoe wood where Fleming wrote all 12 Bond books sits in the corner of the master bedroom.

The original house was so lacking in creature comforts that Fleming’s close friend, the British playwright Noel Coward, called it golden eye, ear, nose and throat because it reminded him of a medical clinic. Coward eventually settled on a property at the top of a nearby hill that he called Firefly, which is now owned and maintained by Blackwell. In between Firefly and Goldeneye was Bolt House, where Chris’s mother Blanche Blackwell, heiress to a banana plantation fortune, lived after her divorce.

Blanche met Fleming in 1956 and became the married author’s friend, reported lover and muse. She gave Fleming a small boat he named Octopussy, which became the title of a collection of short stories and, later, the 13th Bond film. An outgoing nature lover, Blanche – who would stop by for lunch and a snorkel at the reef off Goldeneye’s beach – is said to be the inspiration for both Honeychile Rider, the orphaned woman-child who collected shells in Dr. No (shortened to Honey Ryder in the film), and Goldfinger’s Pussy Galore, a lesbian trapeze artist and ringleader of a team of female cat burglars in the book. In 2017, the year his mother died at 104, Blackwell told Tatler magazine she often said: “I love men. They make such good pets.”

The movies made from Fleming’s books, which stray, as screen adaptations do, from the words on the page, add layers of imaginary characters and locations atop real ones. Add to that all the people who knew Fleming and his pals Coward and Blackwell or who worked on the three movies filmed partly on location in Jamaica – Dr. No, 1973’s Live and Let Die and the upcoming No Time to Die – and the number of people who have a Bond connection multiplies exponentially.

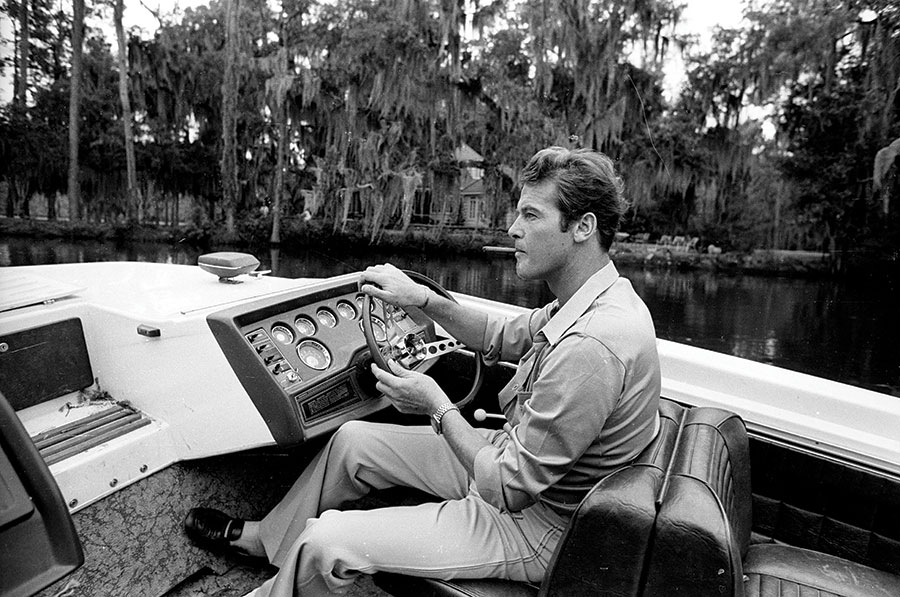

The north shore of the island was Fleming’s playground, and it’s still a Bond mecca. In Ochos Rios, you can visit the Green Grotto Caves, which doubled as archetypal Bond villain Dr. Kananga’s underground lair in the movie Live and Let Die, where Roger Moore and Jane Seymour were filmed trying to escape his henchmen. According to the tour guide, Kananga fell to his death by sharks at the grotto’s underground lake but, when asked how they got the large, metal platform that dangles above the water through the narrow passageways, he shrugs.

Then there’s the Jamaica Swamp Safari Village in Falmouth, where the sign that caught a Live and Let Die location scout’s eye – Trespassers Will Be Eaten – still frames the entrance. Its original proprietor, Ross Kananga, is long gone, but he lives on in a clip shown on-site of a stunt he performed for the movie where he ran across the backs of alligators tied to wooden boxes under the water. Kananga was paid US$60,000 for his troubles, but he also got 193 stitches and a nod in the film when its writers named the villain after him.

Further west, at the luxurious Half Moon Resort in Montego Bay, I meet Heinz Simonitsch and his wife, Elisabeth, who own the white-framed cottage 10 (now numbered 1093). It was used for an exterior shot in Live and Let Die, where Bond breakfasts on the porch with Rosie Carver, a rogue CIA agent played by Gloria Hendry.

“The front of the building is no longer the same,” explains Simonitsch, 93, who managed the resort until he retired in 2002. When the Austrian-born

hotelier arrived from Bermuda to look at the property in 1963, he stayed in the Bond cottage. “It was a full-moon night,” he recalls. “The sparkling water and the breeze – I always visualized that Robinson Crusoe had an experience like I had. And I said for one year I would be here.”

Bond’s Jamaica is full of serendipitous surprises like that. Most tourists sipping colourful cocktails at the Moon Palace Resort on Ochos Rios Bay have no idea Reynold’s Pier is right across the water. A Bond fan will feel a jolt of recognition when they drive by the former bauxite terminal, stained rusty red from the mineral once exported to make aluminum. This was the exterior of Dr. No’s headquarters on Crab Key island, where Bond kills the mad scientist and escapes the pier minutes before it appears to blow up.

If guests leave the comfort of the pool long enough to amble past the wood-fired pizza oven to the tip of the promontory, they will find a crumbling helipad with the 007 logo – a revolver next to the seven – painted in white on the asphalt. According to the hotel, it was used to bring in supplies during the filming of Dr. No. Now the first zero has fallen to the rocks below, a reminder of how much time has passed since Fleming – and Bond – set eyes on Jamaica.

Whether you’re a Bond fan or not, Jamaica’s north coast still offers what Fleming called “peace and silence and cut-offness from

the madding world.” You can picture the author – martini in one hand, cigarette in the other – drinking in Jamaica’s beauty from his cliffside retreat and dreaming up the next perfect ending to Bond’s next escapade.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2020 issue with the headline, “On the Trail of 007,” p. 98.

RELATED:

The 007 Showdown: Who Is the Best Bond Ever?

7 Shaken, Not Stirred, Facts About Roger Moore’s James Bond

Villain, Sidekick, MI6 Pilot? Our Best Guess at Prince Charles’ Potential Bond Cameo