‘Beyond Monet’: Discovering the French Artist — and His Beloved Garden — Through a New Immersive Exhibit

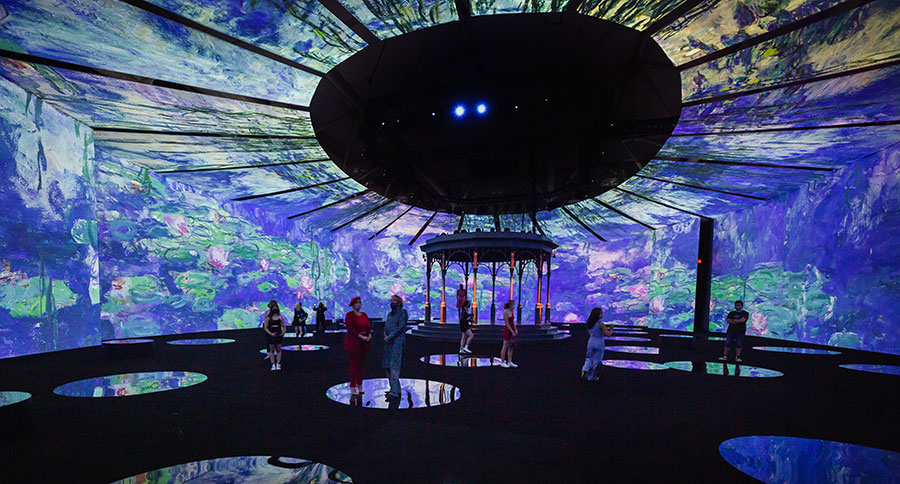

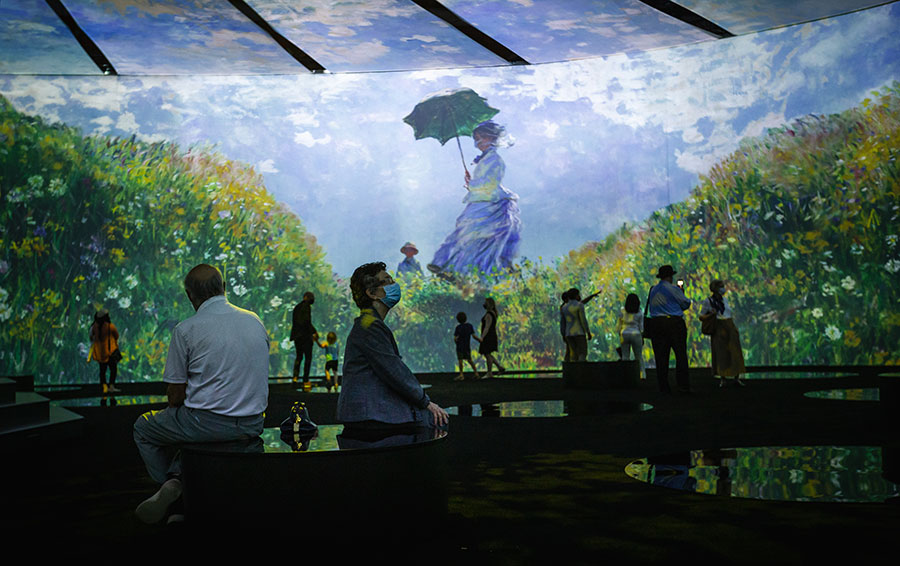

The 'Beyond Monet' exhibit allows patrons to immerse themselves in the French master's works — many of which depict his beloved garden. Photo: Paquin Entertainment Group

Claude Monet’s garden was his life, and his life’s work, so it’s not surprising that the famed French artist had a guy whose express job it was to dust each and every lily pad.

With six full-time employees tending to that famous sanctuary in northern France up until his death in 1926 — relics of which live on in the new blockbuster multi-sensory exhibition Beyond Monet, which made its world premiere in Toronto this week — the garden gives and gives when it comes to the collective imagination. Even (or, especially?) today in the mid-summer span of a city — and world — still in a state of low-hum pandemic disquiet.

As do the stories, which I discovered when I checked in with Fanny Curtat, the Montreal-based art historian brought in to consult on Beyond Monet. Speaking over the phone on the cusp of the exhibition’s premiere, she gave me the lay of the land.

Monet’s garden was in the village of Giverny, where the father of French Impressionism essentially set up shop in 1883. Hiring gardeners to turn it into a tranquil place to paint, Monet had water lilies imported from Egypt and South America and a Japanese-style footbridge erected over a pond. It’s a setting where Monet tried, and tried, to capture the light sifting off the water and those plants that reflected it back.

“He was immersed. Totally immersed,” Curtat explained. “The water lilies — it is a continuum. An endless hole. There is no rupture.”

And as much as there can be something almost quaint about them — those water lily paintings now adorn dorm room wall hangings, tote bags and coffee coasters — Curtat emphasizes that the images were quite novel in their time. And it’s a sentiment that the new exhibition hopes to relay.

“It [was] incredibly shocking and new at the time. It divided the art world. There were newspaper articles: ‘Do not send pregnant women to see the exhibition.’ When you are looking at them, you are looking at a moment. Someone trying to appreciate the here and now.”

That hyper-awareness of the fleeting nature of time, not to mention all that non-stop repetition in his work, seems a fitting testament to this pandemic era.

Like the panoramic nature of the immersive Van Gogh exhibition that showed in Toronto and various other cities last year, this new showcase — produced by the same team at Normal Studios — seeks to bring people into the paintings via both projection and audio.

Asked how conceiving this exhibition was more or less challenging than doing the Van Gogh one, Curtat tells me there was one main distinction: Van Gogh died by his own hand at 37, so his body of work is, alas, much more concentrated. Monet, meanwhile, lived to 86. He produced more than 2,000 paintings. “Van Gogh started to get some traction before he died … they would have reached the same place, I think, had he lived.”

And while Van Gogh had more distinct phases in the evolution of his work, “with Monet, it is harder to see those phases. But the idea of nature is definitely there. An almost abstract quality to his work. You are just in colour. In light. You also see the scope of his work, in his influence later on Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock. In a way, he was doing the first artist installation.”

Turning to the main bullet points of Monet’s life, we discussed his unsupportive father (a merchant who wanted him to focus on the family grocery business, while his mother was “more supportive, but she passed away when he was 16”) and his time both serving as part of the First Regiment of African Light Cavalry, and later, experiencing the ravages of the First World War. As well, the vision problems he began to assume in his 60s (diagnosed with cataracts in 1912, he continued painting by memorizing the locations of different colours of paint on his palette) eventually led to surgery, though Monet always wore sunglasses in the latter years of his life.

And then there’s Monet’s second wife, Alice Hoschedé, who is said to have been vividly jealous of the painter’s first wife, Camille Doncieux, who died at 32. Not to mention one of Hoschedé’s daughters married one of Monet’s sons, meaning the step-siblings eventually became husband and wife! Phew.

Asked if she sees Monet as an optimist, Curtat immediately shrugs off that idea. Like so many artists, he was “more on the depressive side.” She adds, he was “fighting for the beauty.”

Curtat — an art historian who studied in Paris — then made a startling confession to me: early on, she herself had a kind of snobbish reaction to Monet. She did not see him as edgy, and because his work is so ubiquitous, believed it is “easy to overlook it.”

As she really started to delve into the artist, though, Curtat realized the true catharsis of his work. “It is not the kind of art to punch you in the face. It is not doing it. But beyond the ease of it, there is a radical aspect to it.”

Beyond Monet, which is on now at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre, employs numerous COVID-19 guidelines, including timed entrances and enhanced cleaning practices. Click here for more information.

RELATED:

5 Ways to Confront and Overcome the Discomfort of Starting Something New at Any Age

Prince Philip’s Life and Legacy Celebrated With New Windsor Castle Exhibit