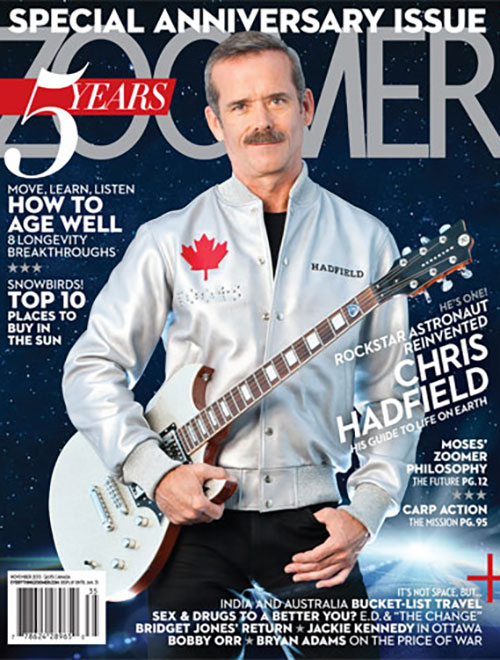

Chris Hadfield Turns 61: Revisiting Our One-on-One With the Rockstar Astronaut

In an interview for Zoomer's November 2013 issue, Chris Hadfield recounts his time as the first Canadian to command the International Space Station. Photo: Chris Chapman

As Chris Hadfield celebrates his 61st birthday (Aug. 29), we take a look back at our 2013 cover story with the celebrated Canadian astronaut.

Chris Hadfield may be on his way to conquering the world one soul at a time, but he has to master a bit of tricky technology first. Canada’s most famous astronaut stares at the small black device on the table, eyes narrowed, muttering.

“Crap,” he says.

He pokes a few buttons, takes a deep breath. If it were me, I’d already have hurled the useless thing against the wall. This is why I have not just returned from a 99,000,000-kilometre space journey, and he has.

Hadfield goes into full Astronaut Mode: See Problem. Identify Problem. Fix Problem. He reads the display on the device, mutters: “Dismiss, caller … Okay, I’ve got it.” He looks up, a smile forming under that celebrated moustache. “Sorry, it’s a new phone.”

There is an obvious joke to be made, and he is known to like jokes. I say, “Are you sure you actually commanded the space station?”

But he is already on the phone to his wife, Helene, whom he had accidentally hung up on a moment earlier, prompting his outburst of mild Canadian profanity. “Hey, beautiful,” he says, and if he were not already perfect enough, this cements it. They’ve been married 32 years, and he still calls her beautiful. It’s too much, really. “Sorry, I was fumbling with my phone.”

They chat for a moment about the prosaic details of life on earth – cars, customs officials, schedules – and he hangs up, fully attentive again. He begins explaining that he and Helene are in the business of moving back to Ontario after 26 years abroad, living primarily in Houston but also in Russia and, for one of them, rattling around the inky vastness of the cosmos. He returned to earth (Kazakhstan, precisely) six weeks ago from his celebrated turn on the International Space Station and he’s been an ex-astronaut for only a few days, having just retired from the Canadian Space Agency.

From outer space to Toronto: surely there’s a joke about downward trajectories in there somewhere, but before I get a chance to say anything, the phone on the table squawks with a tinny, faraway voice. It’s Helene; her husband, the astronaut hero of countless patriotic dreams, has forgotten to hang up. He stares at the phone for a second.

“Crap.”

Here are some things you may not know about Chris Hadfield: he does not like lima beans or liver; he is afraid of heights, which would seem to be an occupational hazard for an astronaut; and he’s quite the storyteller. Here he describes the morning of Nov. 12, 1995, when he was about to be hurled into space for the first time on the space shuttle Atlantis: “We can see the rocket in the distance, lit up and shining, an obelisk. In reality, it’s a 4.5 megaton bomb loaded with explosives, which is why everyone else is driving away from it.”

His new book is called An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, and he wrote it with journalist and author Kate Fillion. It’s part memoir, part self-help manual, part inspiration for a generation that yawns at space travel because it has all the world’s knowledge in its pocket.

Or at least it did yawn, until Hadfield, like a moustachioed sorcerer conjuring with a camera instead of a wand, sparked the world’s interest with his pictures and videos from space. By the time he tumbled back to earth on May 13 after nearly five months in space, half of that time in command of the International Space Station, he had almost a million Twitter followers, had taken 45,000 pictures and left jaws on the floor from Johannesburg to Vancouver.

And now comes the question, which all astronauts face when their boots touch the ground: What to do now? What can compare with that? Some of the earliest astronauts burned up on re-entry, consumed in a fireball of alcohol and womanizing. Many wrote memoirs. Some became motivational speakers (Hadfield has just signed with Speakers’ Spotlight and is already one of their most popular lecturers.) Some turned from the sterility of space to the muckiness of politics. If there were ever a dream candidate to patch Canada’s frayed political quilt, surely it would be the well-loved, spotless Dudley Do-Right of outer space.

“So,” I ask Cmdr. Hadfield, “what about politics?”

Wait: We’ll get to that in a minute. First, we need to talk about space. And being a square astronaut in a round hole.

Orbiting

If you ask Hadfield what stopped his breath when he was up there, he’ll tell you this: once every 90 minutes, the International Space Station circles the earth, and he would try to float past the main observation window, located at the bottom of the craft, at precisely the right minute. “When the moon rises or Venus rises, they actually fall out of the Earth, so it’s as if the Earth gave birth to a very tiny egg.” Wow, he thought the first time he saw it – and the hundredth. He would float to the window and call to his crewmate Roman Romanenko in perfect Russian, “Roman, you’ve got to see this. It’s so cool.”

You get the sense, talking to Chris Hadfield, that things never stop being cool. Even in the unromantic boardroom of his publisher, Random House Canada, even dressed for business in a dark suit and nondescript tie, he radiates the enthusiasm of the nine-year-old moon-mad boy who watched Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s Apollo 11 lunar landing and thought: That’s what I want to do with my life. Now, at 54, Hadfield has the demeanour of a middle-school teacher who teaches shop and science and is equally inspiring at both.

Anne Collins, his editor at Random House, remembers being gripped by Hadfield’s description of docking the space shuttle, which he compared to backing up a tractor.

“He’s got an incredible ability to give you the wonder, to make you feel like you’re right there with him,” she says. “But he doesn’t see himself in the big hero role. Even though he’s done extraordinary things, he doesn’t think of himself as extraordinary.”

It was this ability to connect that made his time on the space station – his third tour of space – such a singular hit. He took breathtaking pictures and sent them back to Earth, assisted by his social media-savvy son Evan: clouds that looked like a white bird over the Black Sea, a deceptively peaceful-looking Syria. People began to take notice and asked him to photograph their hometowns.

“It made me change how I looked at the world,” Hadfield says. “I’d see a city on the east coast of Africa and think, ‘Those people are there on purpose, and they love it there.’ They want to see how their city fits into the world, how their particular us fits into the collective we. I was in a unique position to do that. I found myself inevitably seeing the planet as us. Having the social media and the feedback helped me see that there is only us.”

What resonated equally were the moments when Hadfield unleashed his inner goofball, in wildly popular videos where he demonstrated how to wring out a facecloth or make a peanut-butter sandwich in zero gravity. The response from Earth was thrilling. “It was like hearing the oohs and aahs at a fireworks display.” His response is illuminating: this tough guy, this fighter pilot, this fearless explorer shares a trait with lesser mortals – he likes to be liked.

Later, Helene Hadfield will tell me that the popularity of the videos gave her husband freedom to be himself: “When he started tweeting and people started liking it, it kind of opened a door for him. He didn’t have to be so buttoned up – he could be more himself, more jokey. The more people liked him, the more he felt the freedom and the love.”

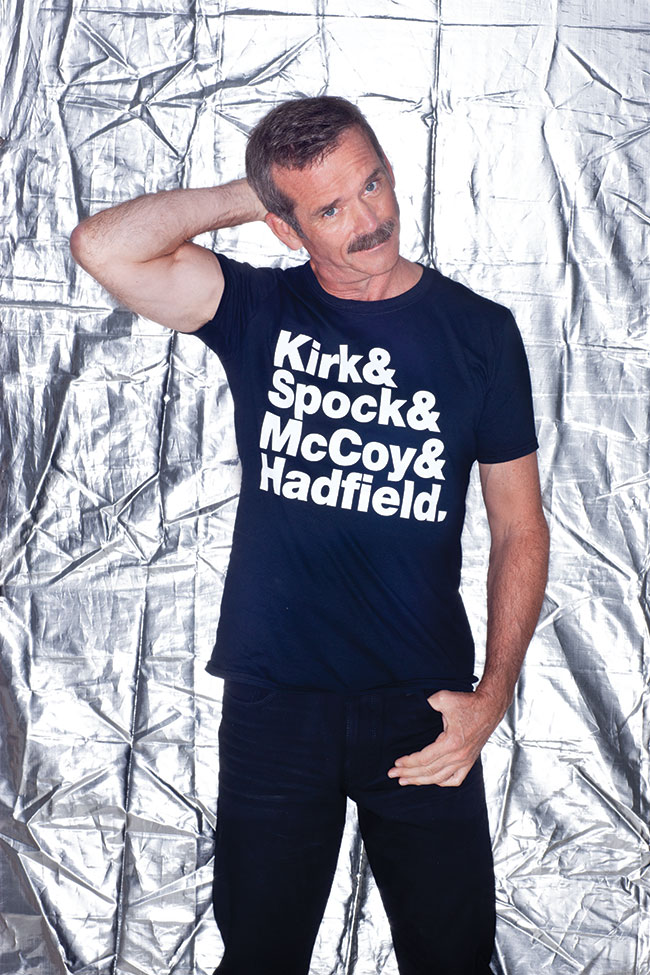

The love culminated, perhaps, with Hadfield’s performance of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” which he sang while floating through the space station, strumming his guitar. Evan rewrote the lyrics to reflect Hadfield’s upbeat view of space travel. Hadfield says, “The astronaut dies at the end of the song, kind of lost, and that’s not how I feel. So I made a deal with my son: if he rewrote the words so the astronaut lives, I’d record it.”

That video now has almost 18 million hits on YouTube. Its fans might be surprised to know that its singer has a much deeper voice in person. There’s no resonance in zero gravity, and sinuses don’t drain. Hadfield spent five months trying to blow his nose. Tears are not an option: as he famously demonstrated in another video, there’s no crying in space.

Not that he had time to cry, mind you. The cheery videos are all well and good, but Hadfield is quick to point out that his time on the Space Station – known as Expedition 34/35 – was filled with real drama (an ammonia leak that forced a unplanned space walk toward the end), real science (he installed a camera that sent back crucial pictures of the floods in Alberta and India) and real consternation. If you want to look at the planet’s wounds, do it from space.

“You directly see climate change and you see the human effects where we’ve locally affected climate, like the Aral Sea. The Aral Sea is a rape – it’s a crime what we’ve done. It’s this huge wasteland.” He points to his mission patch, stuck to the battered cover of his iPad. Each astronaut designs one; Hadfield’s is in the shape of a guitar pick, with three stars representing his children and his space voyages. He placed a blue swath at the bottom to indicate water because water is as crucial as anything we stand to lose through neglect and short-sightedness. One of his NASA missions involved spending two weeks at the bottom of the sea, testing exploration methods; his family’s cottage is on the Great Lakes. “The Great Lakes are as low as they’ve ever been and dropping. Fresh water is so precious, so important to life, yet we treat it as a given till we’ve poisoned it.”

He sits back and chuckles. He really is a science teacher at heart. And yet, clearly this is the path he’s meant to take back on earth: not to chase skirt or drown in a bottle or sell autographs but to tell these stories. About the astronaut who didn’t fit until he did.

Lift Off

Before his initial space walk in 2001 – he was the first Canadian to float, umbilical-tied, through space – Hadfield had trouble getting out the hatch of the space shuttle Endeavour. “It’s the story of my life, really,” he writes in his memoir. “Square astronaut, round hole.”

An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth is about learning to overcome such obstacles, or, as Hadfield writes, “learning to think like an astronaut.” In essence, this means being prepared, not bowing to adversity, taking advantage of opportunities.

He should know since his now famous space trek nearly didn’t happen. A recurring health problem became an issue for NASA and the Canadian Space Agency at a point when he was well into training for the missions, and the two organizations nearly grounded him. But Hadfield pushed on their medical reasoning, wanting it to be sound before a final decision was made, and that persistence paid off. Though he makes it very clear that the mission came first and he would have stood down if there was any risk to the mission, no question. But fortunately the doctors cleared him for liftoff. And the rest, as they say, is history.

It’s a familiar song of self-actualization, although Hadfield, who retired from the Canadian Air Force in 2003 with the rank of colonel, is a wry guru. His kids used to say they would design a “Colonel Says” app that spat out only one piece of advice: “Be ready. Work hard. Enjoy it!”

At one point, he writes, “Early success is a terrible teacher.” This is true but a bit rich coming from someone who seems to have always landed butter side up. The second child in a close family of five siblings, Hadfield was born in Sarnia, Ont., and then moved to Milton, just west of Toronto, when he was seven. His father was an airline pilot, and his parents ran the family farm.

Hadfield grew up on a corn farm; there were chores to do and a two-hour bus ride to school (When I ask Helene Hadfield what first drew her to Chris in high school, she says, “My hormones were racing, and he was a Southern Ontario farm boy who was in massively good shape.”) He was both a fearsome ski racer and a skilled glider pilot by the time he was in his mid-teens. He hurtled through Milton District High School’s enrichment program, graduating a year and a half early.

It does not seem like a life of adversity, I say, and Hadfield tells me a story about sitting in Europe, where he’d gone to bum around after high school, anxious about the future. He was worried he’d never accomplish the dream he’d had when he was nine, looking up at the moon. At that point, Canadians just weren’t astronauts. It would be a decade before Marc Garneau became the first Canadian in space, in 1984. Sitting in Europe, the teenaged Hadfield imagined the kind of life he wanted at age 45 (this alone is astonishing; what teenager wants to think of himself at that wizened stage? But he’s always been a long-range planner.) He wanted a family. He wanted to be a pilot. Mostly he wanted to be an astronaut.

In 1978, Hadfield joined the Canadian Air Force. Fighter pilot to test pilot to astronaut was a tried-and-true path. He married Helene in 1981, and three children – Kyle, Evan and Kristin – followed in rapid succession. He was a fighter pilot stationed in Bagotville, Que., away from home a lot, in a stressful job. She was temporarily derailed from a professional path that would see her working in real estate and IT, among other fields. It was not a recipe for marital harmony.

“Helene had had a great career, and now she was at home,” Hadfield says. “It was just craziness. It drove her nuts. I’d come home, and she’d regularly leave me.”

Helene, who is blond, vivacious and frank – the kind of woman your grandma would call “a pistol” – does not disagree with this assessment. “That was the worst time in our lives. Money was an issue. And kids are hard. We were really young.” One day, fed up, she said to her husband: “You have to decide the kind of life you want when you’re older. Do you want a family and a career or do you just want a career? Because that’s where this is heading.”

Chris Hadfield listened. It’s tempting to think that he looked at his wife’s discontent in Astronaut Mode: See Problem. Identify Problem. Fix Problem. Hadfield pulled the throttle back on work life – a bit, but the effort was enough. And it was a sound decision: he wouldn’t have come this far in life with a fuming co-pilot.

The next great heartbreak came when Hadfield’s spot at a French test pilot school disappeared after a spat between the Canadian and French governments. It threw him into a tailspin: I’ll never be an astronaut, he thought. He was ready to become a commercial airline pilot like his dad. Helene, however, urged him not to give up and, a few months later, Hadfield was selected for test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

In 1992, he noticed an ad in the newspaper: the Canadian Space Agency was recruiting astronauts. This was it! There were 5,330 applicants. Hadfield flew to Ottawa, had his tires kicked and his blood drawn, endured a barrage of psychological tests that included the question, “Have you ever wanted to kill your mother?” Hadfield painstakingly prepared for every task, using a single principle as his guide: “How do I stand out yet not be a jerk?”

He stood out and refrained from jerky behaviour. He was chosen for the CSA program, along with three others. The square astronaut had found his hole.

Re-Entry

Space travel has changed immensely in just five decades. When the first Mercury astronauts – all men, of course – were introduced at a press conference in 1959, they smoked and gave their home addresses. NASA investigated their wives to make sure there wasn’t a Communist in the bunch. For the returning Mercury and Apollo astronauts, life on Earth could be fraught with more danger than life in space.

In his book Moon Dust, about the lives of former astronauts, writer Andrew Smith talks to Apollo 8’s lunar module pilot William Anders about crashing back to earth: “We were rock stars,” Anders says. “It was like being a rock star who’s suddenly had his vocal chords pulled out. … Most came back and found that they were curiosities and celebrities, but that there wasn’t much future in being an aging celebrity.”

No, indeed. Which is why the canny, forward-looking ones became businessmen, like Anders, or politicians like Mercury’s John Glenn or Marc Garneau, who is now the MP for Westmount-Ville Marie and recently ran for leadership of the Liberal Party.

Garneau is a friend of Hadfield’s, so it seems inevitable they’ve talked about this path. As our talk turns to politics, Hadfield’s cheery directness becomes slightly wary. Surely, I ask, it must be odd to go from the order and neatness of space to the chaos of politics?

Hadfield laughs. “You would be surprised at the tumult of actual operations in space flight,” he says. “It’s not black and white. I remember coming back from my first flight and thinking, nothing went as planned. Nothing.”

Hmm, so maybe he would savour the cage match of Question Period, a bit of you-vote-for-my-bill-and-I’ll-vote-for-yours? He smiles and says, calmly but definitively, “By no means is it my intent to get into politics. It’s not my intent.”

Later, I ask Helene the same question and she says – first bursting into laughter and then with her disarming forthrightness, “We’d never do that. I would be the biggest sinker on the political fishing pole that could exist. I am not cut out for that because I will just say stuff.”

They’ve talked about it, she adds, but it’s not part of their long-term plan. Then she says something interesting, which seems to reinforce my perception that Hadfield enjoys his place in Canadians’ hearts and doesn’t want to jeopardize it: “Any one time as a politician, almost 50 per cent of the people don’t like you. That’s something that would make him very sad, and I don’t think it would be good for his psyche.”

What will be good is for Hadfield to have an audience – some 10-year-olds, some CEOs – so that he can spread the gospel he’s been preaching ever since he became an astronaut: “It’s a message about self-determinism and how to organize your life so that you can accomplish the things you believe in and to not miss opportunities.”

The Hadfields are the type of planners who make doomsday preppers look haphazard. (Their plan contains 18 steps mapping out the next four decades, in case you want to feel inadequate about your own goals.) Chris Hadfield’s speaking schedule is already nearly full for 2014. By settling in Toronto, he is fulfilling a promise he made to Helene almost 30 years ago, that they would return one day to her hometown.

I notice that when they speak they use the pronouns “I” and “we” interchangeably; they really are a unified force, a team of two. Helene still sounds like a schoolgirl with a crush when she talks about what “a good guy” she married, the man who takes equal care fixing a washing machine or a spaceship, who always stops to pick up litter by the road or answer a child’s question.

Surely, I say to her, it must be annoying to be married to the awesomest dude in the universe. She bursts out laughing again: “That’s the sickening thing – he is pretty frickin’ perfect! The only reason I can stay with him at all is that he doesn’t have an ego about it. But sometimes I think, really? Do I have to live with this? What aren’t you good at?”

This notion of flawlessness is batted aside by her husband. He’s merely a square astronaut who learned to fit into a round hole. We chat a bit more at his publisher’s office, and then our time is done. He stands, offers a handshake that has not been diminished in zero gravity and heads off to meet his better half.

Walking outside, I notice a slice of moon in the late afternoon sky. Hadfield is a supporter of continued lunar exploration; there’s a lot still to be learned there, he says. He also thinks that we will live on Mars one day, but the technology isn’t ready yet. Unlike some doomsayers, he is bullish about the future of manned space flight. I think of something he said during our interview, when it seemed for a moment as if I were speaking to the nine-year-old with stars in his eyes. “We don’t fly in space because it’s easy or because it’s simple,” he said. “We do it because we just barely can. That’s what exploration is.”

RELATED:

Astronaut Chris Hadfield Talks Fame, Mars and His New Documentary

Chris Hadfield Releases New Album, Recorded in Space

Why the Success of the SpaceX Rocket Launch Is Reason to Consider Humanity’s Future and Its Past