Tim Johnson Takes His Dad to Sweden and Reconnects With His Scandinavian Roots

Photo: Tim Johnson

The cold, crisp, cloudless sky is bright, with some unseen force manipulating the stratosphere, lighting up the night. The heavens going green, everything above us swims across the horizon, a moving wave, curling, swirling, changing from second to second. Standing next to my father in a frozen field just a bit below the Arctic Circle, we’re both clad head to toe in warm snowmobile suits, heavy boots set firmly in the squeaky snow. A little bit of ice on his beard, his face formed into a look of wonder, my dad says, just one word — and it’s in Swedish. While I’m unsure of the exact translation, I’m pretty sure I know what he means.

In some ways, I’ve been waiting for this moment my whole life. Not so much the Northern Lights — I’ve seen those before, and they’re always magnificent. But rather, just being here, in Sweden with my father.

You see, the happy little house in which I grew up, on a quiet street in Peterborough, Ont., was always like a tiny slice of Scandinavia, and my dad, Ellwood Paul Johnson, was perpetually in a Swedish state of mind. Born in Canada and raised in near Erickson, a small Manitoba village with a large Scandinavian population — a recreated Viking ship still dominates the main street of his hometown — Dad, now 70, spent his childhood in a sort of microcosm of the old country.

His ancestors — my ancestors — emigrated here from the central region of Dalarna way back in 1895. They were part of a massive wave. Dealing with widespread economic hardship — and even starvation — due to crop failures, coupled with a population boom, some one million Swedes came to North America in the latter decades of the 19th century until the start of the First World War. The area around Dad’s childhood home formed the first Swedish colony in Canada and was originally called New Sweden. His family continued to do lots of traditional Swedish things and speak Swedish among themselves, with his father designating certain nights of the week for Swedish-only conversation.

He would regale my sister, Lisa, and me — sometimes against our will — with stories about Uncle Harold and Cousin Knute and going to his grandmother’s house to eat herring and lutefisk. He always cheered for Sweden in the Olympics and international hockey, crying out “Sverige! Sverige! Sverige!” every time the team with the three crowns on their chests tallied a goal. Our home displayed several blue-and-white Swedish flags, as well as ubiquitous “Dalarna hest,” ornately painted orange wooden horses. To this day, my dad still swears in Swedish.

But he has only been back to the home country once, almost a half-century ago in 1971, at the tail end of a backpacking trip across Europe (although his well-tended roots have become even more important since my mom passed away from a sudden and devastating brain aneurism five years ago). I only know about 10 words in Swedish, and they’re all weird – the phrase for “crazy dog,” (which my father says every single time he sees a dog), for example, as well as the words for “Close the fridge!” (which I learned as a hungry teenager). Together, we’re here to rediscover those roots and, for me, to learn more about my Swedish-ness.

We start our journey in Stockholm, a city that Dad barely remembers from his first visit, basing ourselves in a hotel owned by ABBA member Benny Andersson on Sodermalm, a newly hip neighbourhood on a southern island within walking distance of Gamla Stan, or Old Town. Now on the ground in the motherland, I look forward to seeing Dad speak with real Swedes. His version of the language learned and spoken in isolation for more than a century, in rural Manitoba, he speaks in a dialect I like to call “time-capsule Swedish.”

We spend three days wandering around the capital. Admitting he’s a bit rusty, Dad starts out slow, in terms of actual conversations, trying just a few small interactions, at first — “Hello!” and “How are you?”-type chats. But everywhere we go, my dad seeks to fortify his language cred in other ways, pointing to random buildings and translating signs – gold, shopping, bank – while, when leaving stores, he booms out the Swedish words for thank you – tack så mycket!

Dad’s paternal grandmother lived in Stockholm before undertaking village life in rural Manitoba. While strolling through the newly reopened National Museum, Dad turns to me, as if struck by a memory. “I feel her presence here,” he says, noting that she loved the arts. A seamstress by trade, she took every opportunity to indulge, when she could afford it. “She would go to the theatre every time she could scrape up enough kroner,” Dad tells me.

And then, we head to Dalarna, home of the hest, to meet our family. My aunt had provided phone numbers for the Hallgrens, and I set up a meeting with them — “Hi, my name is Tim Johnson, and I think we’re related” — I say, when phoning from the hotel in Stockholm. The family history is a bit complicated, but tracing the family tree that Dad holds in his head, we figure out that Jenny Hallgren and her sister, Josefine, are second cousins to him, once-removed to me. Their mother, Marianné, is a cousin by marriage, and their grandmother, Lisa, was my sister’s namesake.

We take the train to a town called Avesta and meet Jenny on the platform, standing there, smiling, with her young daughter, Alice, at her side. We hug, and the connection is immediate. “We are very nervous about our English,” Jenny says with a note of apprehension in perfect English. Travelling a few minutes across a pastoral landscape dotted with tidy wooden houses, all of them painted in traditional falun red and trimmed with white, we arrive in the village of Jularbo at the house where Dad spent a whole week, back in 1971, spending the majority of his time hanging out with Jenny and Josefine’s father, Anders, who has since passed away.

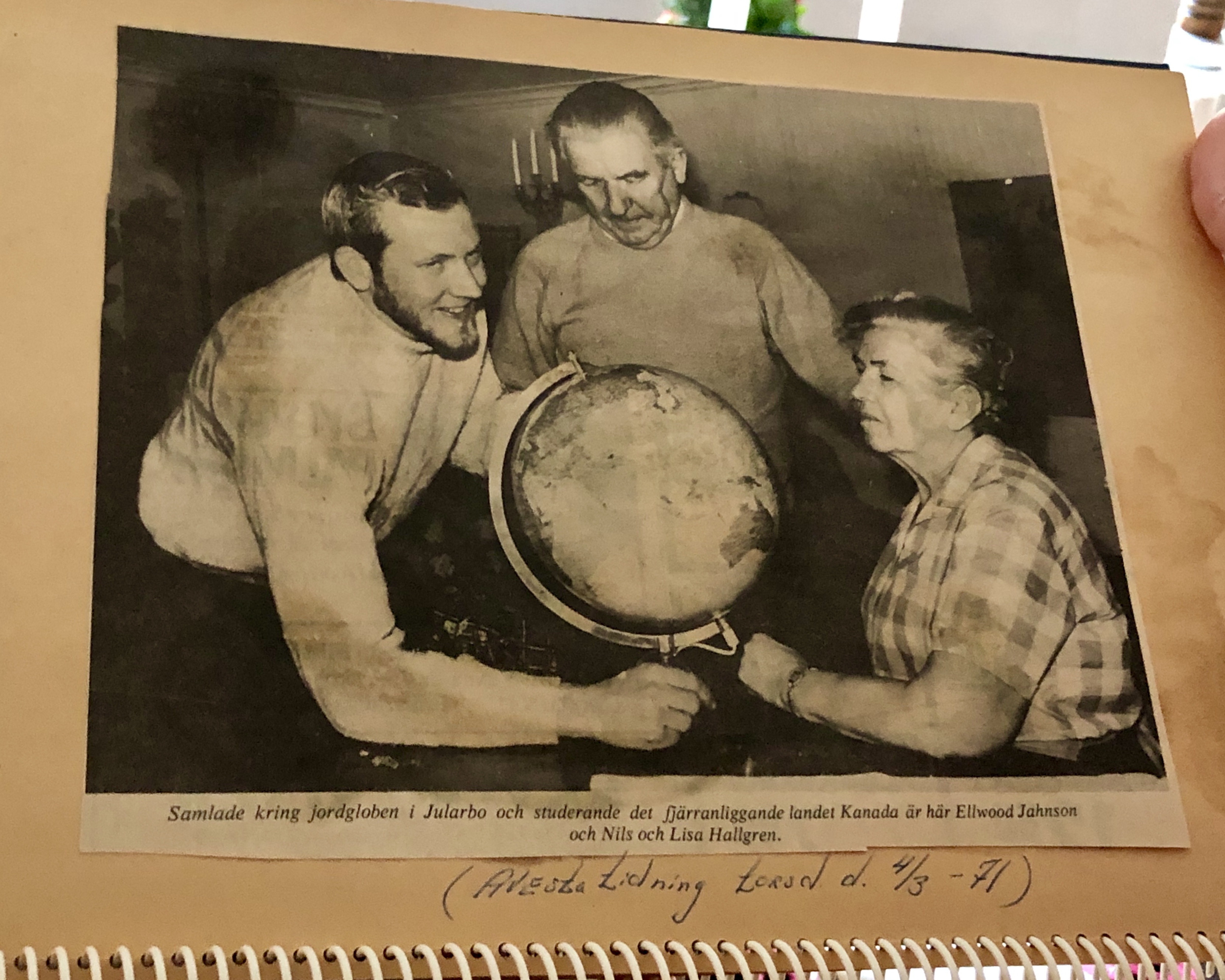

Welcomed warmly, it’s an afternoon of laughs, memories paired with a hearty lunch of Swedish meatballs. Pulling out a series of leather-bound albums, the Hallgrens show us family photos, Dad narrating with each turn of the laminated pages — one of which holds a now-yellowed half-page newspaper picture of my father together with Lisa and Nils, Jenny and Josefine’s grandfather. Much younger but still bearded, he’s leaning toward a desktop globe with a canny smile — apparently, when he came through town the first time, Dad’s travels across the continent made him a minor celebrity here.

And it’s here that Dad’s Swedish begins to flow. Comfortable, over his jet lag, in the region of his roots, he’s able to switch over and carry on conversations with the relatives and, on a little trip around town, with a couple of old friends. I stand back, impressed at his ability to communicate. For the rest of the trip, Dad surprises people along the way, who can’t quite believe this Canadian-born man can still speak the language so well. (When I quietly ask one of them if he speaks with an accent, she thinks for a moment and then says, “The way he speaks, it’s very pure.”)

Promising to keep in touch and after posing for photos under the world’s largest Dalarna hest, we proceed further north. The family history becomes increasingly scant, but our Swedish adventures seem to grow bigger with each additional degree of latitude. At the northern end of the region, we spend several nights at Stilleben, a stylish boutique lodge that specializes in typical traditional Swedish experiences – there, we sit in a lakeside wood-fired sauna and then learn how to make tunnbröd in a communal village oven, seeing how life’s been lived in this part of the country for centuries, doing the things my ancestors would have done before their departure across the Atlantic to Canada.

Boarding the overnight Arctic Circle train and riding through a raging snowstorm, we arrive in Lapland, disembarking and making our way to the village of Jukkasjärvi (or “meeting place by the water” in the local Sami language) and the world-famous Icehotel. Created out of two-ton blocks of ice cut from the frozen Torne River, we’re booked into an Art Suite, with a double bed set on a frame of ice, surrounded by ice carvings. Despite the steady room temperature of -5 C, Dad insists that he wants to stay in the cold room. After an afternoon of feeding reindeer (and sledding behind them), he beds down there, while I sleep in town at a motel. (It’s common for those who are unsure whether they will make it through the night in those chilly circumstances to book a back-up motel room, either on site at the lodge, which had no vacancy the day we were there, or down the road in town.) In the morning, he seems a bit weary but somehow energized. “It was an experience,” he says, with a smile. “Once in a lifetime.”

We finish at another landmark hotel, the Treehotel, a three-hour rail journey toward the coast, spending two nights high among the pines in the 7th Room — a high-end tree house 10 metres in the air once occupied by another Canadian — Justin Bieber. We go dogsledding and hiking and, on our last night, we ride behind a snowmobile, out to a clearing — spending a couple of hours under the glowing Northern Lights. A fire crackles nearby, our host waiting with mugs of steaming lingonberry juice. But we hang on, out there in the cold, in our boots and suits, for just a few more minutes. “What a marvel,” I hear Dad say, in English this time. “Just marvellous.”

IF YOU GO

50 Degrees North specializes in Nordic and Scandinavian travel, adventures above the 50th parallel. Run by Scandinavians with a Canadian office in Vancouver, they offer more than 200 pre-set and self-directed itineraries itineraries (from expedition cruises to small group journeys to rail-ferry combinations) as well as tailor-made trips like the one we took. With contacts throughout the region, they also offer 24-hour support. https://www.fiftydegreesnorth.com/

Icelandair provides the most direct link between Canada and Sweden, with year-round flights from Toronto and Vancouver, and seasonal routes from Edmonton, Halifax and Montreal, via Keflavik International Airport. Their Saga Premium Class includes top-shelf food and wine that includes local selections (like reindeer steaks). https://www.icelandair.com/

MORE TRAVEL STORIES:

A Paris Memoire: How the City Came to Hold a Lifetime of Memories For Me

Make It Eco-Friendly: An Unforgettable Multi-Generational Journey to Antigua