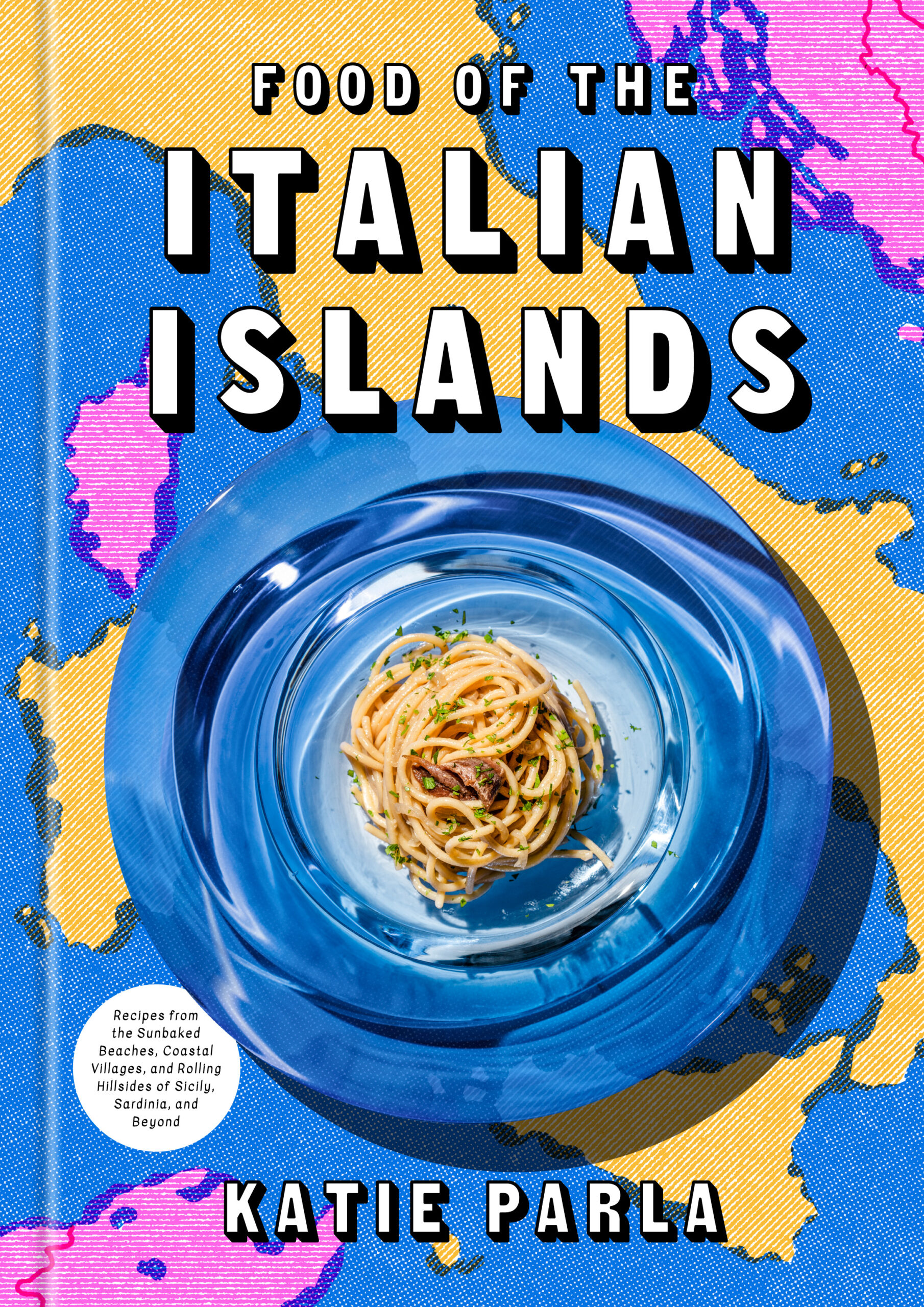

‘Food of the Italian Islands’: Lauded Food Writer Katie Parla Shares Recipes, Stories and Dispels Myths

Seadas — the delicious regional dish of Sardinia — consist of fried, cheese-filled ravioli soaked in honey. Photo: Ed Anderson

Katie Parla, the New York Times bestselling cookbook author and Emmy-nominated television host (appearing on shows like CNN’s Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy and Netflix’s Chef’s Table), celebrates the diversity of Italy’s regional dishes in her new book Food of the Italian Islands.

For Parla, who was born in New Jersey, the book — which is packed with over 85 original and reimagined recipes — is a return to her Italian roots. Zoomer caught up with Parla to talk about the cultural history and flavours of Sicily, Sardinia and Italy’s lesser-known island destinations. And to bring home a taste of these cultural gems, we serve up some of her palate-pleasing pasta recipes, including Fried Cheese-Filled Ravioli Soaked in Honey and Pistachio Pesto. Mangiamo!

Italian food is incredibly popular outside of Italy and you’ve become an ambassador of sorts for it. However, since you’ve studied its food and culture, are there any myths you’d like to dispel?

Yes, I think there’s a romantic stereotype about the way that we eat in Italy, and then there’s the reality of the way that we eat. Italians are frugal people. They don’t go out to dinner every minute; they simply can’t afford it and it’s not the custom. There’s a lot of home cooking.

I think ambassador is a fair word, but maybe with sharper teeth that’s not diplomatic all the time. As I started writing, I [encountered] restaurants who were cutting corners on ingredients, ignoring sourcing and there are a lot of labour issues here. So, I was definitely vetting places, not just on their flavour, but also on their ethical approach and their relationship with their staff, which was an important feature for me. I created really curated lists and articles about lost and disappearing dishes and why those are important.

Essentially, you are helping to preserve history or identify things that could be lost because they might not be trendy?

For sure. We need to have a real conversation about what’s going on in the city and culture and the way that people eat and how that’s changed. I think food is in constant evolution everywhere, so I don’t believe in trapping a city’s cuisine in amber.

A lot of people kind of gloss over the complexity of Roman food. But this notion that Roman food is cucina povera (poor food for peasants) is not true even in times of deep poverty. (Also, what we ate 50 years ago was a very impoverished diet, and people now have protein and all sorts of variety.) There were certainly prime cuts that were consumed by the elite who could afford it, but offal is delicious if properly cooked. So why would the elite not eat something that tastes great? What they would do is put fancy spices on that no one else could afford in there to symbolize their status.

I have so many cookbooks about Rome, but it’s not the food that we eat every day. As someone who is really devoted to the late 20th and early 21st century food systems here, I thought the Roman cookbooks [could use] a refresh, so Tasting Rome came out in 2016.

It’s also very interesting and important to document the things that are becoming less common and vanishing. That was kind of the driving force behind Food of the Italian South (2019) because I was going to all these remote villages and interrogating everybody about what [was traditionally made] and then trying to find documentary sources or interviewing people about their experiences, and then developing recipes based on those thoughts.

Are there any examples of a dish that has transcended time?

It’s in Food of the Italian South. Everyone in Italy can afford a loaf of bread. Back in the day, bakers would go around town pushing carts and people would bring out their bread loaves to the baker who would [just] do the baking, but not the dough making. That’s your bread for the week, so you’d have to make it last, and it would go stale after a few days. [They would] fry the breadcrumbs and use it as a condiment — it’s also used in posh restaurants now — that they would substitute for cheese.

And, even if now you can afford fresh bread, bread casseroles taste great, so why would you give up making those cheesy, tomatoey, herby brothy casseroles that evoke nostalgia but align with periods of poverty and deprivation? It’s also a symbol of what the ingredients of that place could do to nourish people. I love those things that you make from scraps that are often the simplest, most delicious, also tend to be vegetarian and are often legume based because people needed their protein source in ways that were shelf stable.

How did you choose to focus on the Italian islands as your third deep dive into the country’s regional cuisines?

It was really hard. It’s important to me to choose a subject that I have established expertise in; that I feel like I can write something that will be valuable to people. I have a big passion for Rome and chose to live here for a long time. I am obsessed with the south and I deliberately excluded Sicily, because I didn’t want it to steal the thunder from Molise, Basilicata and Calabria and other lesser-known regions. So, when it came time to think about the next book, I thought of the Italian islands. I love Sicily and Sardinia. Those islands are very different culturally. And the fact that people were literally isolated meant that they were developing their food in a similar spirit: What can I cellar? What can I preserve? And how far away can I stay away from the coast and its invaders, pirates and bad weather? So, I thought it would be a really interesting project to look at the necessities of island people and then document the recipes that were iconic from those places.

Sicily and Sardinia are the first- and second-largest islands in the Mediterranean. So, I went back through my travel journals and photos from old iPhones to see what I had documented, and then thinking about the places I’m not familiar with, not seen or thought about and then mapping out this multi-year research project. I started in 2018 and would dip in for a weekend and do some research, spending time with farmers, home cooks, pasta makers and people who are reviving cheese traditions.

A lot of it happens organically when I’m on the ground. My strategy whenever I’m researching for people who are making really interesting food is to hit up the local natural wine shop or the natural winemaker in an area because they want food that’s made in a super traditional way, without any chemicals or synthetic pesticide intervention. They’re going for all the obscure cheeses and heirloom grains. When they’re eating meat, it’s meat that is raised on a small farm. It’s all the things that we kind of envision about Italy.

What was one of the surprising experiences you had?

When you go to Sardinia, you usually have the beach in mind, but most Sardinians are living inland, not on the sea. There’s an incredible, super seasonal food culture that you can experience yourself.

There’s a beekeeper, Luigi Manias, who has hives all over the mountains of Ales because he’s making corbezzolo (strawberry tree) honey that’s incredibly floral and almost has a bubble gum undertone. It makes a really fun foil for seadas (fried cheese-filled ravioli) that are in the book. So, you can go hang out with him and walk through a forest with Neolithic ruins because the beehives are in these really remote places. There’s a lot of people [who are producing] food that defies economics (it’s much more profitable if he made honey almost any other way).

What other flavourful finds did you encounter?

There’s a section in the book that’s devoted to pesto. When most people think of pesto in Italy, the idea that comes to mind is the pesto from Liguria or Genoa. There’s almost a law about what you put in it, but pesto is literally a pulverized condiment that you use to dress pasta. The nuts change all the time depending on what part of the islands you’re in. So Pantelleria, Linsoa and Trapani have their own pesto that is made with the stuff that grows there, like almonds or pistachios. The absence or presence of tomatoes changes the colour and flavour profile.

There’s also a pasta that’s made in the Barbagia region [of Sardinia] called su filindeu. So, what’s interesting is that the same article keeps getting written about it that says only two people make it, but that’s not true. A lot of people are making it — a lot being dozens of people, but it’s not a dying [craft]. Su filindeu is a great example of food that was verging on extinction, or at least a rarity, and now has been revived just through the hunger of Sardinians to learn about their own super regional cuisines.

If you work a lot with dough, you’re told durum wheat dough is not extensible. If you pull it, it will break. That’s why all over Italy they make stubby little, funny-looking pasta shapes like orecchiette or cavatelli with it. But, if you really overwork the gluten and you’re in constant contact with this dough, it will become extensible. It’s a very meditative process, and it pushes your knowledge of elasticity, extensibility and your relationship with the dough to the very edge.

Su filindeu is such an incredible pasta by tradition because people would make it and pull it over these wicker disks in diagonal layers, dry it and then they would break it. There’s such an incredible amount of labour that goes into something that is ultimately broken into pieces. And then you cook it in mutton broth with cheese and eat it. If done properly, it’s like velvet on your palate. It’s just an incredible experience. (There also are QR codes that take the readers to videos of the book to show the techniques.) If you want to make the same broth with cheese [recipe at home and you can’t find su filindeu], use angel hair.

How do you hope Food of the Italian Islands will inspire people?

Outside of maybe Palermo and Catania [in Sicily], the places I cover in the book don’t have 50 guidebooks on them. These are places where you can have a real adventure. Where you can encounter real, live Italian people where they live, support their businesses and eat the things that they’ve worked really hard to prepare. Try the cheeses that are made from techniques passed down for generations. You can’t do that on the Costa Smeralda next to a super yacht, you know what I mean. That’s something that has to happen with a car rental and full insurance coverage. I love it!

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

RECIPES

Pesto di Pistacchi

Pistachio Pesto

“Made from herbs and ground pistachios from around Mount Etna, this has become a modern classic and is served all across the island and even on the mainland as an ode to Sicily. The pistachios are the star here in the absence of tomato and the bright green hue is as alluring as Sicily itself.

“Pestos are super easy to pull together, and you can make a big batch and freeze it,” says Parla. “You don’t have to just use it on pasta. You can drizzle it over toasted bread or some cheese.”

Makes 1 1⁄2 cups pesto, to serve 4 to 6

Ingredients:

1 cup shelled unsalted raw pistachios

Leaves from 1 bunch basil (about 1 packed cup)

Leaves from 1 bunch mint (about 1 packed cup) 2 garlic cloves, peeled

Fine sea salt

1⁄4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1⁄2 cup finely grated aged caciocavallo or Pecorino Romano cheese

1 pound fresh or dried pasta

Directions:

- Bring a large pot of water to a rolling boil over high heat.

- Meanwhile, in a food processor, combine all the ingredients except the olive oil, cheese (if the recipe calls for it), and pasta, then pulse until chunky. Slowly add the olive oil and process until smooth.

- Transfer the pesto to a large bowl. Stir in the cheese, if using.

- When the water comes to a boil, add salt until it tastes like a seasoned soup. Add the pasta and cook until al dente if it’s dried or cook until it floats and loses its raw flavour if it’s fresh.

- Drain the pasta, reserving some of the cooking water. Add the pasta to the pesto and stir to coat. Add some of the reserved pasta cooking water a spoonful at a time as needed to loosen the sauce. Season with salt to taste. Serve.

Seadas

Fried Cheese-Filled Ravioli Soaked in Honey

“The first time I visited Sardinia, I ate seadas at every meal. Like pane carasau and fregula, this once regional food has been popularized throughout Italy, likely because its components — melted cheese inside a fried dough parcel swimming in honey — are extremely delicious. The tangy cheese traditionally used in Sardinia is hard to track down off the island, so use a fresh pecorino or any acidic white cheese you love that’s a good melter. When you’re on the island, eat lots of it. And look for the brass seadas cutters and ornate pasta wheels sold in hardware stores for achieving a decorative edge.”

Tip: “If you can’t get corbezzolo honey, you can use other honeys like chestnut which has a deeper, nuttier flavour,” says Parla. “But when people are thinking about the best expression of this delicious dessert, the corbezzolo honey is what a lot of people are thinking of.”

Makes 6 seadas

Ingredients:

1 cup plus 2 tablespoons “00 flour” or all-purpose flour, plus more for dusting

¾ cup plus 3 tablespoons semolina flour

2/3 cup water

2 tablespoons good-quality lard

12 ounces fresh pecorino cheese, coarsely grated

Zest of 1 orange

Neutral oil, such as safflower oil, for frying

½ cup honey, warmed

Directions:

- Combine the “00” flour and semolina in a large bowl, then make a well in the middle. Pour in the water and use a fork, then your hands to incorporate it. Knead until smooth. Pinch in the lard and knead until it is incorporated and the dough is smooth and supple, about 5 minutes more. Wrap the dough in plastic wrap and set aside for 30 minutes.

- Meanwhile, combine the pecorino and orange zest in a medium pan over medium-low heat, stirring constantly until the cheese is fully melted. Pour onto a baking sheet and spread into a ¼-inch layer. Set aside to cool.

- Transfer the dough to a work surface lightly dusted with flour and roll to a thickness of 1/8-inch thick. Cut the dough into twelve 4-inch diameter disks. Cut the pecorino into six 3½-inch diameter disks and place each one on top of a 4-inch disk. Lay the remaining disks on top of the pecorino and press gently around the cheese, eliminating any air bubbles and ensuring the dough fits snugly around the cheese and is pressed together around the edges. Using a seadas cutter, decorative pasta wheel, or fork, press the edges closed to leave a pattern. Transfer to the refrigerator to set for about 30 minutes.

- Fill a medium frying pan or cast-iron skillet with 1 inch of neutral oil and heat the oil over medium-high heat to 375 F. Fry the seadas in batches, turning once to ensure even browning and puffing, 2 to 3 minutes. Drain on paper towels and serve hot, with warm honey drizzled on top. Fried seadas do not keep well, but any uncooked ones can be stored in a sealed container in the freezer for up to 1 month. Thaw completely before frying.

Su Filindeu in Brodo di Agnello

“Threads of God” Pasta with Lamb Stock

“Before visiting the Barbagia, the Sardinian subregion where su filindeu is made, I had read about the pasta. Sources were pretty much in agreement that su filindeu, which translates to “threads of God,” is the rarest pasta on the planet, and is made by just three women. As much as I enjoy the easy access to travel journalism in our modern information age, it’s important to remember to fact-check your sources, because writers and editors don’t always do that essential step for the reader. As with many articles about Italian food culture, the statement was false and hyperbolic. Su filindeu is a regional specialty, for sure. It was born in northeastern Sardinia, where each May and October it is made by hand, dried, and broken into a lamb or mutton broth, which is then spiked with a tangy melted cheese. The dish is distributed to pilgrims for the feast of San Francesco. But the traditional dish is also reliably on the menu at restaurants — Il Rifugio in Nuoro serves it year-round — and even local bars and cafeterias. It’s taught by a handful of food educators like Gianfranca Dettori, my teacher, keen on keeping Sardinian traditions alive. It’s even found in Japan, where Claudia Casu, an ambassador of culture for her native island, teaches classes on making su filindeu and other intricate Sardinian pasta shapes at her Sardegna Cooking School. This once hyper-regional pasta is hardly on the verge of extinction.

“The shape itself is spectacular, and emblematic of Sardinia’s ritual devotion to food. When dried, the pasta looks like woven textile, and cooked, it feels like velvet on the palate. Su filindeu is beautiful. Help keep it alive wherever you are and make it at home.”

Tip: The acidulated cheese used in Lula for this dish is virtually impossible to track down outside Sardinia. Substitute a soft, tangy fresh pecorino or cow’s-milk cheese that melts easily. Use the best quality meat you can find. It will pay huge flavour dividends in the final stock.

Serves 4 to 6

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 pounds bone-in lamb or mutton shoulder, cut into 2-inch pieces

1 carrot, roughly chopped

1 medium onion, halved

1 celery stalk, roughly chopped

1 bay leaf

Sea salt

1 recipe Su Filindeu, broken into 3-inch pieces OR 1 pound dried angel hair pasta, broken into 3-inch-long segments

4 ounces pecorino fresco cheese, coarsely grated

Directions:

- Heat the olive oil in a large pot over medium-high heat. Add the lamb and cook, turning frequently, until browned on all sides, about 15 minutes. Turn off the heat and carefully pour out and discard the lamb fat. Return the pot to the stove and add enough water to cover the lamb by an inch or two. Bring to a simmer over low heat, skimming off any scum that rises to the surface. Add the carrot, onion, celery, and bay leaf and simmer, skimming the surface occasionally, until the meat is fork-tender and nearly falling off the bone, at least 1 hour.

- Strain the stock and set aside the lamb and aromatics to serve as a main course. Pour the stock into a clean large pot. Bring to a boil over high heat. Season with salt. Add the su filindeu and cook until the pasta has lost its raw flavor, about 3 minutes.

- Meanwhile, divide the cheese evenly among four to six individual serving bowls. Ladle over some stock to melt the cheese, then divide the su filindeu evenly among the bowls and serve.

Recipes and images courtesy of Food of the Italian Islands by Katie Parla (Parla Publishing LLC).

A version of this story was originally published in September 2023.

RELATED:

A Taste of Italy: Recipes and Culinary Tips From Chef Eron Novalski

Discover the True Taste of Italy With 3 Recipes From Celebrity Chef Massimo Capra